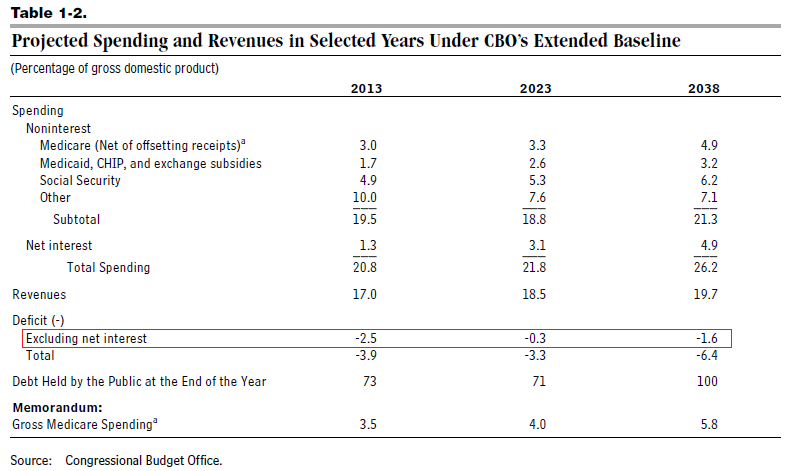

On Tuesday, the Congressional Budget Office released its new projections (pdf) for the long-term budget. A Bloomberg article titled “CBO Says Short-Term Deficit Cut Won’t Avert Fiscal Crisis” provided a fairly typical summary:

[F]ederal spending will rise from 22 percent of GDP in 2012 to 26 percent in 2038 … The deficit [currently 3.9 percent of GDP] would be 6.5 percent of GDP in 2038, greater than any year between 1947 and 2008 … Even though tax receipts would grow …, the revenue increase wouldn’t be “large enough to keep federal debt” from “growing faster than the economy starting in the next several years,” according to the CBO report.

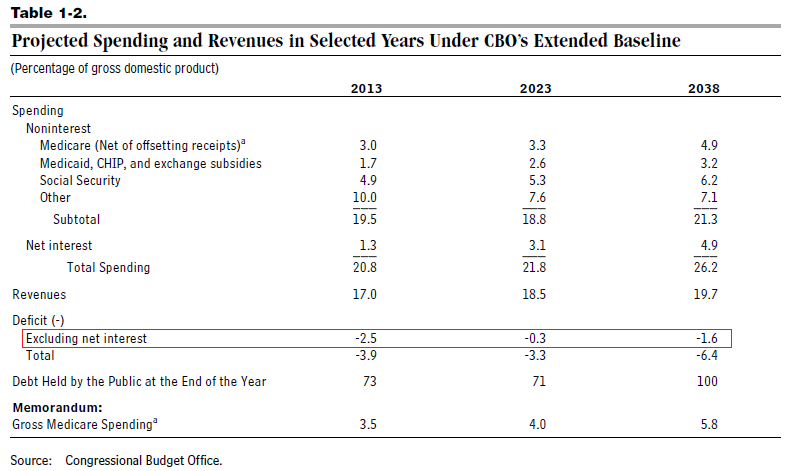

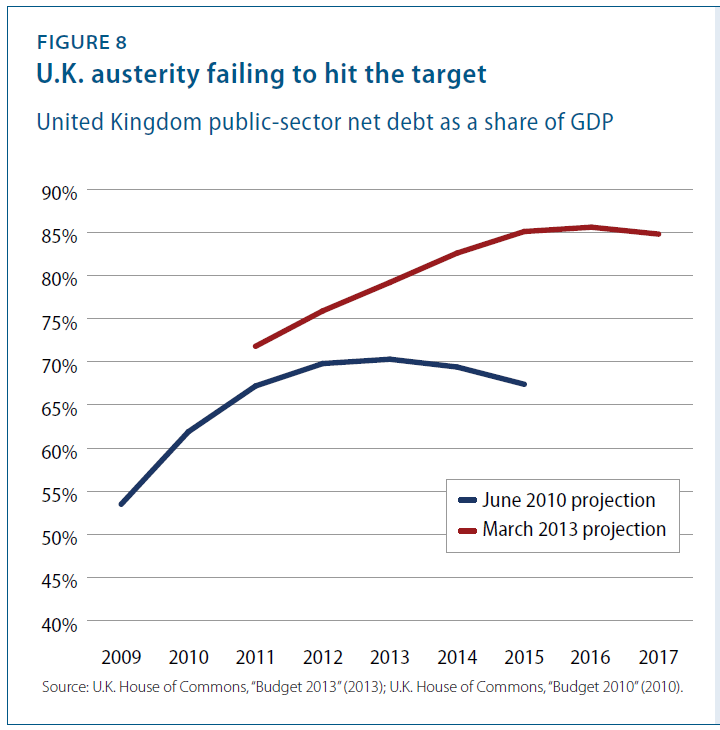

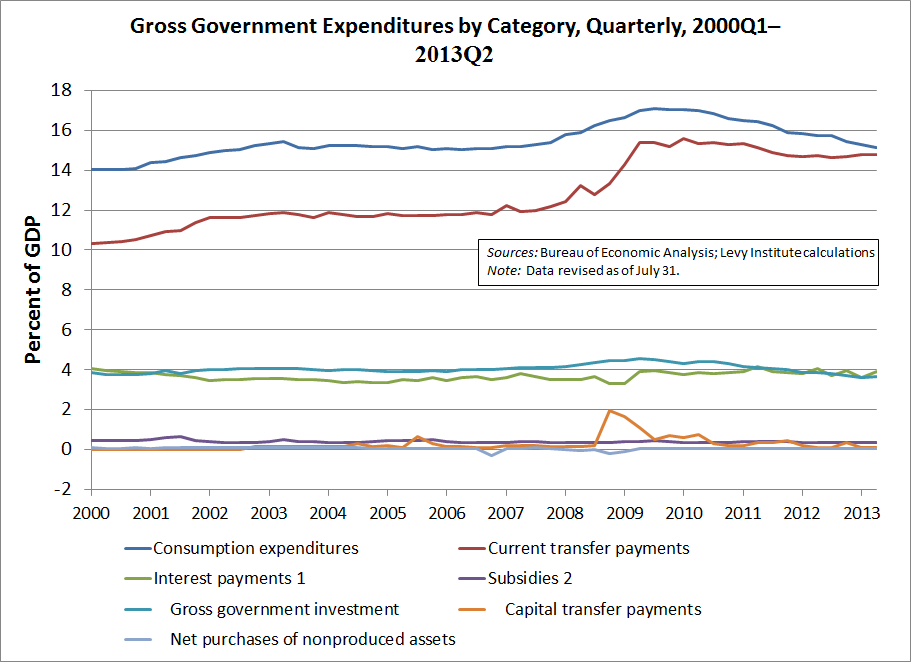

Here’s another way of presenting those CBO numbers. Spending on actual government programs is projected to fall from its current 19.5 percent of GDP to 18.8 percent in 2023, before rising to 21.3 percent in 2038. And revenues are also projected to rise, from 17 percent to 19.7 percent of GDP by 2038. The result, according to the CBO, is that the primary budget balance (that is, excluding interest payments) shrinks from its current level of -2.5 percent of GDP to -0.3 percent in 2023, and then grows to -1.6 percent of GDP by 2038.

In other words, a quarter-century from now, the primary deficit — the gap between tax revenues and the spending under Congress’s control — will be smaller than it is today, according to the CBO’s numbers. Here’s the relevant Table:

Nonetheless, the CBO’s extended baseline tells us that debt will rise from its current 73 percent of GDP to 100 percent of GDP by 2038. The key here is the interest payments — CBO’s prediction of rising interest rates over the long term (and the near term, for that matter).

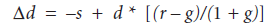

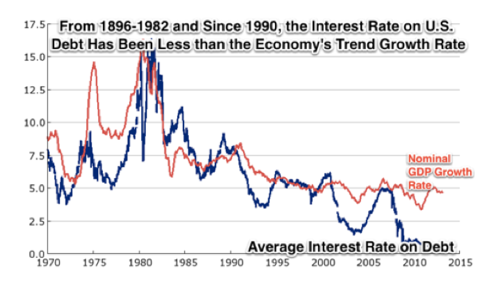

This is the sentence from the CBO report that tells you all you need to know about those predictions: “under the extended baseline, interest rates would exceed the growth rate of the economy” (p. 26). To see why that’s significant, look at this equation from Willem Buiter (or skip over it and wait for the explanation):

What this means, as James Galbraith explained in this policy note, is that if the rate of interest on government debt (r) is above the rate of economic growth (g), then any primary budget deficit will lead to an “unsustainable” path for the debt over the long term — in the narrow sense that the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise without limit.

By contrast, if r is below g, then even what would normally be considered a “large” budget deficit (Galbraith uses the example of a continuous primary deficit of 5 percent of GDP — well above what CBO is projecting over the next few decades) will be “sustainable” over the long term, in the sense that debt will eventually stabilize as a percentage of GDP.

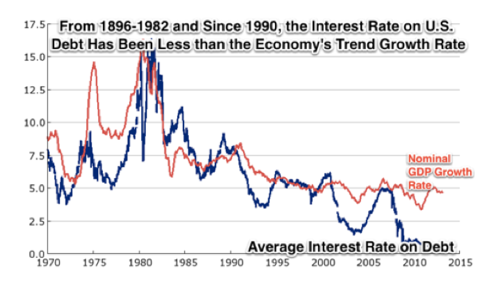

For most of the postwar history of the United States, with the exception of the 1980s and part of the ’90s, the rate of interest on government debt has tended to be below the rate of economic growth. Underlying the CBO’s projection of an ever-rising debt ratio is its assumption that over the next few decades, that will no longer be the case; that for some reason, the exception of the 1980s will become the rule.

(chart from Brad DeLong)

ShareThis

ShareThis