What Happens if We Don’t Raise the Debt Ceiling? A Stock-Flow Analysis

Some commentators and members of Congress have insisted that failing to raise the debt ceiling would not necessarily require defaulting on the national debt. The theory is that Treasury could prioritize payments to bond holders while defaulting only on commitments to other payees (say, Social Security recipients).

Most of the discussion of what might happen if Congress fails to raise the borrowing limit has focused on the financial market consequences of defaulting on the debt. But even if prioritization is possible (there is some debate about whether it’s logistically possible, or even legal), we would still be facing a serious macroeconomic crisis.

This is because failing to lift the debt ceiling would require extreme spending cuts some time after October 17. Essentially, the federal government would be forced to balance its budget. (This is all assuming that trillion dollar coins and premium bonds are off the table.)

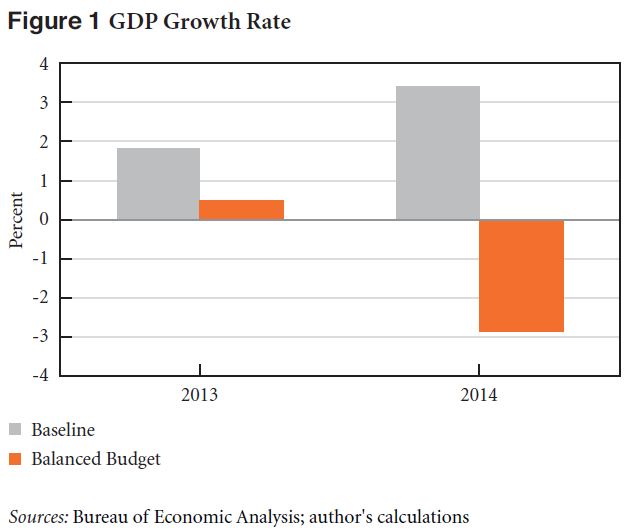

What would that kind of radical austerity do to the economy? Michalis Nikiforos uses the Levy Institute’s macroeconomic model to estimate the effects of beginning rapid fiscal consolidation in the last quarter of this year and maintaining a balanced budget through the rest of the 2014 fiscal year (which is to say, through 2014Q3).

The result? A big swing in the expected growth rate, leading to a deep recession:

Nikiforos stresses that if anything this underestimates the economic damage:

(1) the simulation relies on the IMF’s forecast for US trading partners, which currently assumes a reasonably healthy US economy. But “[a] recession in the United States would certainly exert a negative influence on growth in the rest of the world, which would in turn feed back to the States.”

(2) the private sector’s balance sheet is still fragile. If the US enters another steep recession, it could induce “a new round of rapid deleveraging, which would further push down the growth rate” (and, Nikiforos suggests, probably cause problems in the financial sector).

(3) fiscal stabilizers helped place a floor under the economic collapse during the Great Recession, but this time around, automatic and discretionary fiscal stabilizers would be AWOL due to the need to maintain a balanced budget. “In the case of a new crisis originating from rapid fiscal consolidation,” he writes, “it is not clear who would play the role of system stabilizer.”

Read the policy note here (pdf).

As of today, it looks like John Boehner is trying to get House Republicans to agree to a short-term increase in the debt limit, of perhaps six weeks. If this passes and is accepted by the President (it’s not crystal clear right now whether there will be any demands attached to the House’s debt ceiling increase), we’ll be back on the edge of this macroeconomic crisis around Thanksgiving.

Update: No deal

@michlstephens

ShareThis

ShareThis