Dimitri Papadimitriou, Greg Hannsgen, Michalis Nikiforos, and Gennaro Zezza have just published a new strategic analysis for the US economy, with a baseline projection and alternative policy simulations through the end of 2016. The report takes a closer look at the potential payoff of R&D investment in the context of a US export strategy.

As Papadimitriou et al. point out, fiscal policy at the federal level is simply stuck on a self-defeating course, with nothing but further growth-killing contraction on the horizon. Their baseline projection shows that if we stay on the current fiscal path, in which the deficit continues to shrink rapidly, growth won’t be high enough to appreciably bring down the unemployment rate — as far out as 2016 unemployment would be just below 7 percent.

The significant increases in federal spending that would be needed to accelerate the recovery and quickly bring down the unemployment rate don’t seem to be politically viable, to put it gently. So the authors turn to the external sector; more precisely, to an export-oriented strategy driven by innovation.

Research and development may be an area in which a proposed increase in government investment would attract less rabid congressional opposition. And from the authors’ perspective, recent revisions to the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) now allow us to get a better handle on what to expect from this sort of strategy: “we now enjoy an improved ability to conduct an inquiry in this area: R&D activity is the largest change to measured US GDP, with the recently revised NIPA concepts treating this sort of spending as a form of investment.”

They examine the effects of an increase in R&D spending of $160 billion per year (around 1 percent of GDP) through the end of 2016. This would be R&D expenditure focused on fields with applications in the tradable goods and service sector. In addition to the fiscal stimulus effects, part of the mechanism here is that innovation would increase average productivity in these export sectors, reduce unit costs and relative prices, and thereby boost export volume (“We assume that this spending is aimed exclusively at reducing domestic costs of production, although in reality the effects might also include bringing novel products to market overseas”).

The results of the R&D simulation show that unemployment would drop below 5 percent by the end of the projection period (2016Q4), with economic growth nearing 5.5 percent. Their simulations also suggest that R&D investment would be slightly more potent than the same amount invested in infrastructure, though the authors don’t present this as an either/or policy choice.

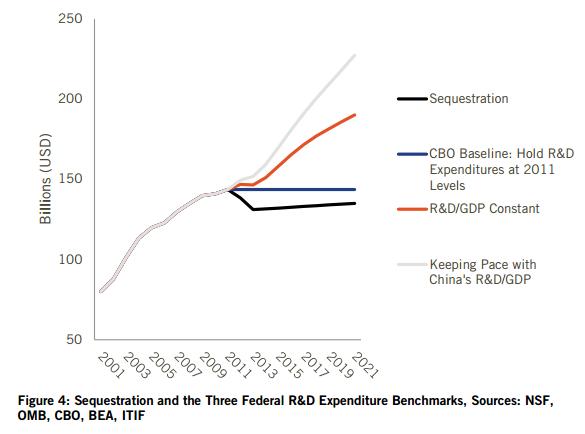

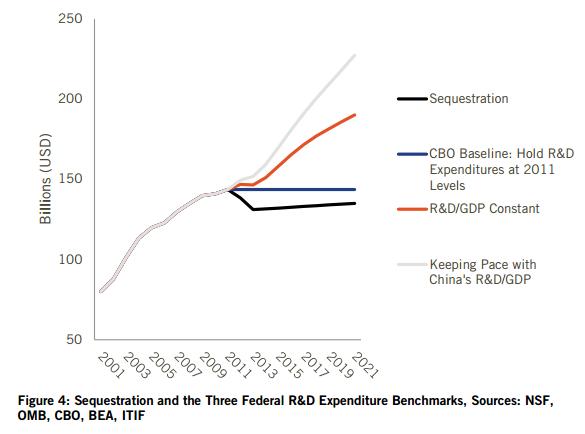

The result is particularly noteworthy, given that the meat-axe approach to federal budgeting over the last couple of years has meant that government investment in R&D has been stagnating — and is scheduled for big cuts (from ITIF, via Brad Plumer):

Papadimitriou et al. also introduce a note of caution in their new report. Many economic forecasts assume that the post-financial-crisis deleveraging process — the reduction of the private sector’s debt-to-GDP ratio — will end shortly. In other words, a lot of growth projections for the next few years assume renewed household and business borrowing.

The authors run a simulation in which deleveraging continues for households in particular. Why should we consider this possibility? “Following the work of Wynne Godley, we think it reasonable to argue that historical norms are relevant as benchmarks for household indebtedness ratios.” In this instance, taking that approach would mean treating the private sector’s negative net saving from the 1990s through the 2000s as an exception.

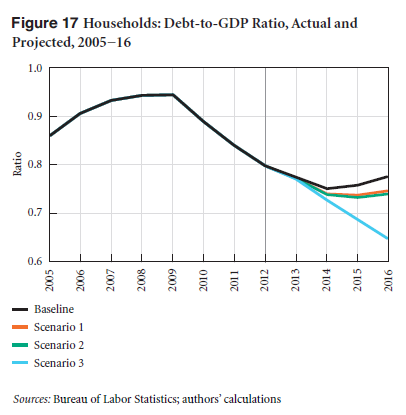

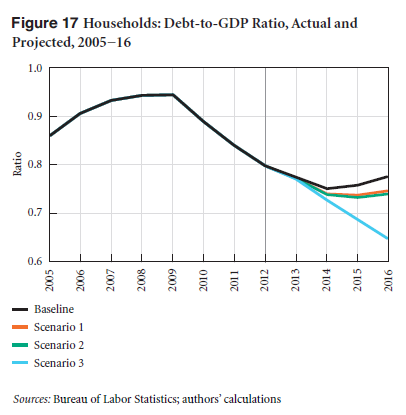

This is what household indebtedness would look like in this scenario (“scenario 3” in the figure, which includes the R&D investment of 1 percent of GDP per year. “Scenario 1” and “scenario 2” correspond to the infrastructure and R&D investment scenarios, respectively, but with the CBO’s more optimistic assumptions about the path of household debt):

If households continue to reduce their debt levels, the positive effects of the R&D investment would be somewhat blunted: growth would just fail to reach 5 percent by the end of 2016 and the unemployment rate would be about 5.5 percent (compared to sub-5 percent unemployment for the R&D scenario in which the household deleveraging process ends).

The upshot is that policymakers need to be prepared for the possibility that the deleveraging process is not finished. If households continue to reduce their debts, there will be even more drag on the economy — and an even more urgent need for ambitious thinking about policies to boost growth and employment.

You can read the report here (pdf).

ShareThis

ShareThis