Are Structural Reforms the Cure for Southern Europe?

I have recently signed the “Economists’ Warning” on the situation in the eurozone, which states that

It is essential to realise that if the European authorities continue with policies of austerity and rely on structural reforms alone to restore balance, the fate of the euro will be sealed.

The Economists’ Warning was published by the Financial Times (“European governments repeat mistakes of the Treaty of Versailles,” September 23), and a reply by Professor Gilbert of the University of Trento appeared in the Letters section on September 25.

Professor Gilbert seemed to imply that the Economists’ Warning was advocating external support for Southern European countries in trouble — a position that is not apparent in the original document, which only advocated “concerted action” among eurozone members.

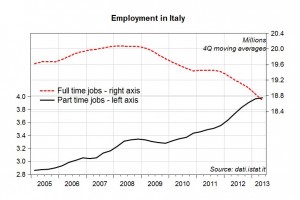

My reply to Professor Gilbert was published late last week in the Letters section of the Financial Times. I argue that structural reforms have already been implemented in Italy: such reforms aimed at cutting pension payments to generate a structural reduction in the government deficit (matched of course by a reduction in the purchasing power of people in retirement) and increasing flexibility in the labor market. The chart below documents the dramatic drop in employment since 2007 — almost one million jobs, with a fall in full-time positions of 1.77 million partially compensated by 813,000 new part-time positions.

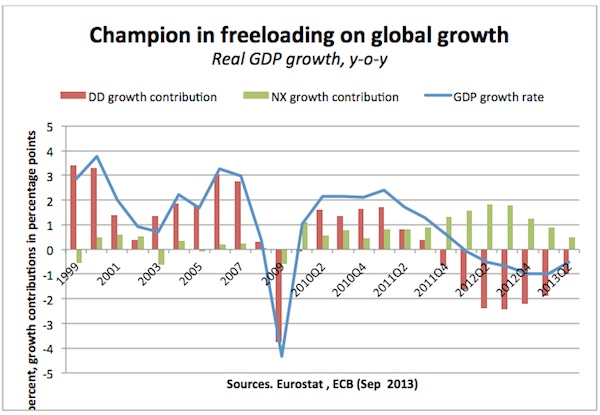

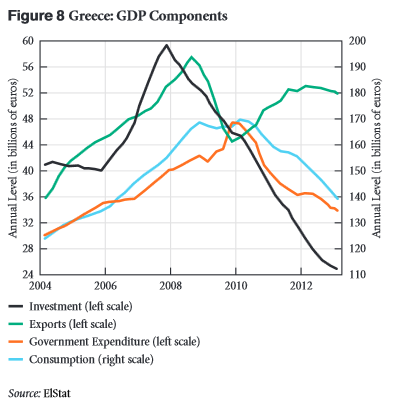

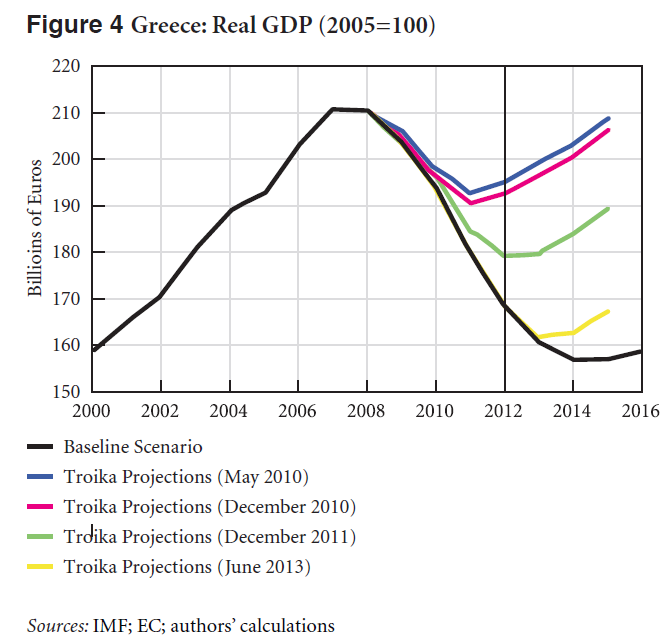

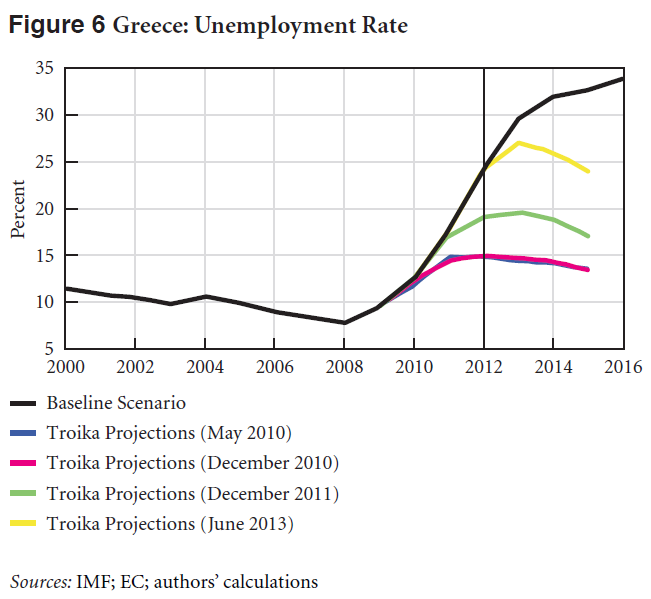

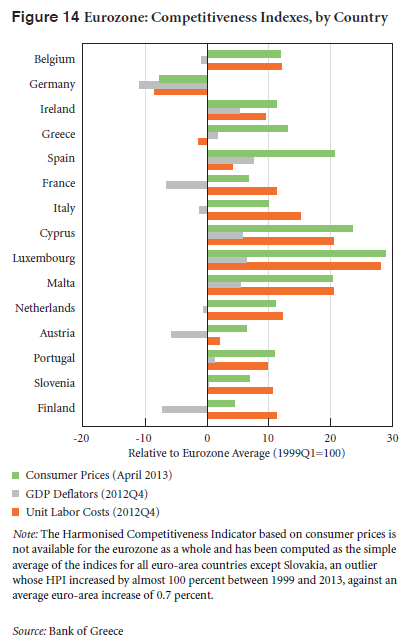

In a recent report on Greece we have argued along similar lines: structural reforms and austerity have pushed the unemployment rate to unprecedented levels, and increased competitiveness achieved through lower labor costs has done (and will do) little to improve the external balance, while it has contributed to a dramatic drop in domestic demand.

Professor Gilbert responded to my letter in the Comments section of the Financial Times, and since I hope this discussion could be of interest to others (the Letters section of the FT is only open to subscribers), I would suggest continuing it on this blog.

First of all, what strikes me in Professor Gilbert’s reply is his view of economists as a group of scientists who share the same beliefs: continue reading…

ShareThis

ShareThis