Are Structural Reforms the Cure for Southern Europe?

I have recently signed the “Economists’ Warning” on the situation in the eurozone, which states that

It is essential to realise that if the European authorities continue with policies of austerity and rely on structural reforms alone to restore balance, the fate of the euro will be sealed.

The Economists’ Warning was published by the Financial Times (“European governments repeat mistakes of the Treaty of Versailles,” September 23), and a reply by Professor Gilbert of the University of Trento appeared in the Letters section on September 25.

Professor Gilbert seemed to imply that the Economists’ Warning was advocating external support for Southern European countries in trouble — a position that is not apparent in the original document, which only advocated “concerted action” among eurozone members.

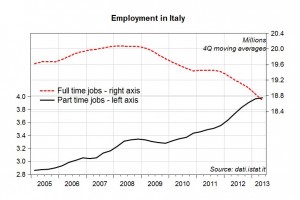

My reply to Professor Gilbert was published late last week in the Letters section of the Financial Times. I argue that structural reforms have already been implemented in Italy: such reforms aimed at cutting pension payments to generate a structural reduction in the government deficit (matched of course by a reduction in the purchasing power of people in retirement) and increasing flexibility in the labor market. The chart below documents the dramatic drop in employment since 2007 — almost one million jobs, with a fall in full-time positions of 1.77 million partially compensated by 813,000 new part-time positions.

In a recent report on Greece we have argued along similar lines: structural reforms and austerity have pushed the unemployment rate to unprecedented levels, and increased competitiveness achieved through lower labor costs has done (and will do) little to improve the external balance, while it has contributed to a dramatic drop in domestic demand.

Professor Gilbert responded to my letter in the Comments section of the Financial Times, and since I hope this discussion could be of interest to others (the Letters section of the FT is only open to subscribers), I would suggest continuing it on this blog.

First of all, what strikes me in Professor Gilbert’s reply is his view of economists as a group of scientists who share the same beliefs:

Economists believe in incentives …

Economists favour equality…

Economists believe in the exploitation of comparative advantage …

I thought that since the start of the Post-Autistic Economics Movement and the failure of mainstream economists to see the crisis coming, economists should be (more) aware of other approaches to macroeconomics that don’t rely on the imaginary world of rational, forward-looking agents. The University of Trento used to offer a pluralistic approach, with outstanding personalities such as Vela Velupillai and Axel Leijonhufvud; not to mention the reputation of Trento in behavioural economics, which showed — among other things — that what many economists believe about incentives and rationality is not applicable to the real world.

Getting to the specific points Professor Gilbert raises:

Italy, it appears, is in the best possible of all worlds. Professor Zezza cannot be serious.

On the contrary, it is clear from my letter and The Economists’ Warning that Italy is already in a deep crisis which requires an immediate policy response, while Professor Gilbert seems to suggest that such a crisis has not arrived yet.

Reform processes are blocked by special interests. Any particular reform will inevitably result in loss of privileges or monopoly power by some section of society even though the country as a whole benefits. Countries which fail to reform find themselves in the bad corner of the Prisoners’ Dilemma matrix. It requires either a major crisis or external pressure (often both) to force a move to the good corner of the matrix. This has always been the justification of IMF and World Bank conditionalities.

I thought you would move to the good corner of a Prisoners’ Dilemma through cooperation among the players. IMF and World Bank actions have very often privileged some social groups while causing losses to others.

I agree that some privileges — la Casta! — have to disappear, but I contend that if having a full-time job, which decreases uncertainty about one’s future economic conditions and allows one to form a family and raise children, is a privilege, then such privileges should be extended, rather than eliminated.

In the end, the unsustainably high level of Italian debt and the massive social exclusion generated by labour market malfunction will force a crisis in which Italy will, like Greece, need to choose between Eurozone exit and externally imposed radical reform.

The idea that massive social exclusion in Italy is generated by the inability to fire (labor market malfunction) — in the face of a credit crunch and austerity policies — does not deserve further comment. As for the “unsustainably high level of Italian debt”: its sustainability depends on the rules of the game for debt roll-over and access to credit. Other countries, such as Japan, have larger, but sustainable, debt. The rules for public debt management are, IMHO, among the changes advocated by the Economists’ Warning for avoiding the breakdown of the eurozone. I have argued elsewhere that, should Italy leave the eurozone, its public debt would immediately be manageable.

Coming finally to Professor Gilbert’s proposals for reform:

Economists believe in incentives. Currently, tax levels on both firms and employees are too high. It would be advisable to shift taxation [from] those who make money to those who have money. IMU on first houses should be retained with possible exemptions on low value properties. Bequests and gifts should be taxed. This would allow reduction of taxes on income and employment.

I don’t believe that firms are not investing (only) because the tax burden is too high. Austerity implies a fall in expected profitability, which is much more relevant. However, I entirely agree that shifting taxation from labor to wealth is a move in the right direction. I would add that more reasonable — and progressive — income tax rates coupled with a serious attack on tax evasion would imply a redistribution of income in the right direction, with perceptible effects on aggregate demand.

Economists favour equality. Current labour market law discriminates between those who have permanent jobs and those who have temporary jobs and even more acutely between current employees and potential employees. Youth unemployment is massive and without action will grow further. Employment of additional workers is an investment decision and, with terminations virtually impossible, is a long term investment decision. Firms choose to invest in labour-saving machinery rather than in labour since machines can be scrapped or sold on. Alternatively, they transfer their activities to countries where labour laws are more favourable. The “politically impossible” solution is a system in which firms can terminate contracts, subject to a specified and possibly generous tariff but without the danger of being taken to court and being obliged to re-employ the sacked worker. The distinction between permanent and temporary workers would then become redundant and de-industrialization would be reversed.

I fail to see how a society in which all workers are uncertain of their employment next month would be better. It is certainly true that this will improve profitability.

Italy has too many levels of government. It would be easy to totally abolish provinces, strengthening communes and regions.

Why not? Let’s abolish provinces and create new departments to address all the problems currently taken care of by provinces. It may increase efficiency in local governments, but it would not make a dent, IMHO, in current macroeconomic conditions.

As Professor Zezza will be aware, regional differences in Italy are enormous. This results in certain parts of the country, the state is the major employer resulting in a tendency towards clientism. (This is a problem which is probably even more acute in Spain). Decentralization of wage bargaining together with an element of fiscal devolution would result in enhanced fiscal responsibility.

I fail to see the connection between clientelism, wage bargaining, and fiscal devolution. Clientelism should be prosecuted effectively in all regions and at all levels. Lower wages in southern regions and smaller fiscal transfers from richer to poorer regions will surely contribute to a further exacerbation of the crisis. It is one of the ideas implemented in Greece.

Economists believe in the exploitation of comparative advantage. Italy’s very clear comparative advantage is in culture and tourism but the state offers little support to these industries. Industrial policy should be redirected from the support of ailing large manufacturing and towards culture and tourism. many small and medium sized manufacturers are performing well despite the recession but they are typically not beneficiaries of government largesse or protection.

Comparative advantages in modern societies are created through (publicly funded) long-term investment in human capital, research, and innovation. It is certainly true that some Italian regions could improve their attractiveness with regard to tourism and culture, but there is a limit to the amount of tourists you can host on a beach. Specializing in low productivity sectors may not be such a good idea.

Everything I have suggested here is fiscally neutral. None of it requires any European or international support. Each of these reforms will be opposed by one or other special interests and by the political parties that represent these interests. Taken together, they would increase Italian competitiveness and, over time, raise growth, reduce unemployment and reduce social exclusion. For now, it is up to the Italians to decide. But it is up to university professors of economics, such as you, Professor Zezza, to take a responsible and positive position.

My responsible and positive position is that austerity policies are doing damage and will not by themselves generate the reforms that Italy needs. Most of the problems we need to address in order to improve efficiency and equity — eradicating organized crime, moving to a more equitable tax system, helping start businesses — require more government expenditure, coupled with efficient monitoring processes (end of clientelism). And the policies we need to improve long-term prospects require, again, more government expenditure on education, research, and probably some infrastructure; not to mention the short-term need to sustain employment and profitable businesses, many of which have been brought to bankruptcy by the credit crunch.

ShareThis

ShareThis