Greg Hannsgen | June 12, 2013

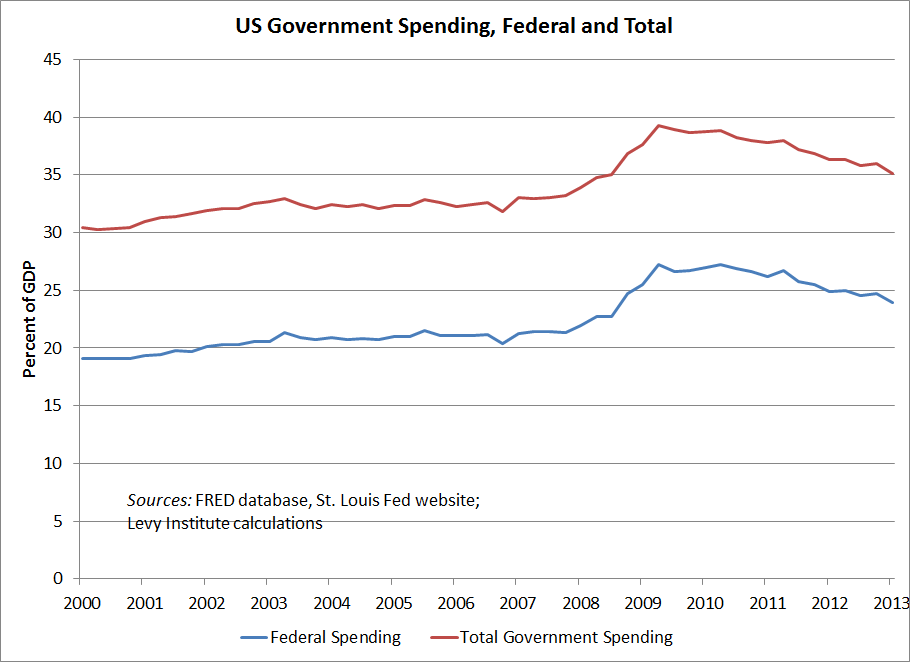

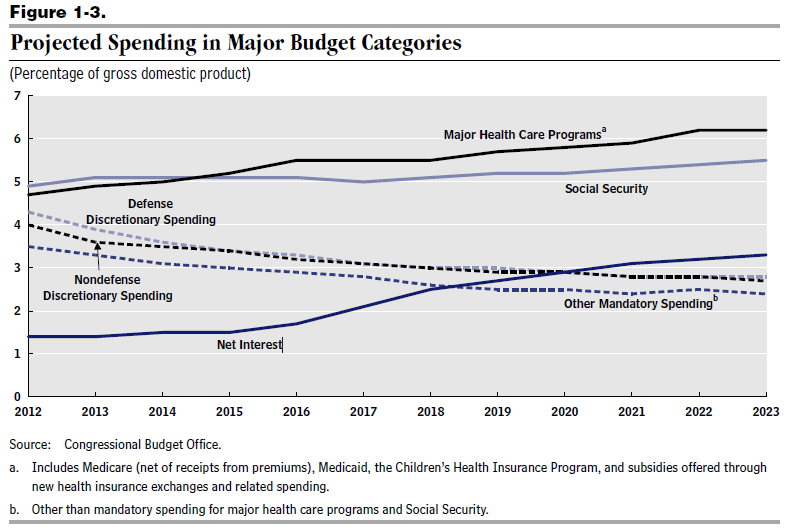

I used a figure like the one above in a talk that I gave at the Eastern Economic Association 39th Annual Conference last month on the topic “Heterodox Shocks.” (The diagram above incorporates data released at the end of last month.) Total government spending in the US, shown in red, continues to fall as a percentage of GDP. Similarly, federal spending is trending downward following a 2009Q2 peak. The effects of the spending sequester, which technically went into effect on March 1, have probably not been fully felt yet in the Q1 data.

My talk was intended only to be a thought-provoking discussion of the concept of shocks in macroeconomics (including policy shocks) and does not contain, say, a complete new economic model. It began with two concrete examples from recent data, including the one above, which may be of some interest to readers who have followed the Institute’s work on the recent move to austerity in US fiscal policy, in this blog and elsewhere on our website. For those interested, a revised working paper version of the conference paper just went online and is available at this link. Finally, this Powerpoint file may be of interest to readers looking for an outline-style summary of the talk and paper, though it contains some additional visual examples and could be described mostly as a pitch for the paper.

Comments

Michael Stephens | June 7, 2013

Today in the Guardian, Philip Pilkington notices the British Labour party potentially inching away from their scaled-down proposal for a “job guarantee,” an idea fleshed out by Hyman Minsky:

Minsky’s theories of financial instability suggested that capitalist economies were prone to serious downturns in which huge amounts of the labour force would find themselves unemployed. What’s more, this would lead to large shortfalls in demand for goods and services which would further exacerbate such downturns. The result was a vicious circle that would become worse and worse as the financial system evolved into an increasingly fragile entity and households and businesses became increasingly mired in debt. …

While progressive taxation and unemployment benefits went some way toward both protecting workers and propping up demand during downturns, it did not, according to Minsky and his followers, go nearly far enough. They believed that governments should offer a job to anyone willing and able to work and then pay for these jobs by engaging in increased deficit spending …

Read the whole thing. Pilkington notes that the original Labour proposal differed from Minsky’s “employer of last resort” in both its scope (limited to the long-term unemployed) and its compulsory nature (the ELR is meant to be voluntary, in Minsky’s original formulation), but the proposal did at least represent a departure from the Conservative government’s fixation with the budget deficit and an attempt to do something about the long-term unemployment crisis.

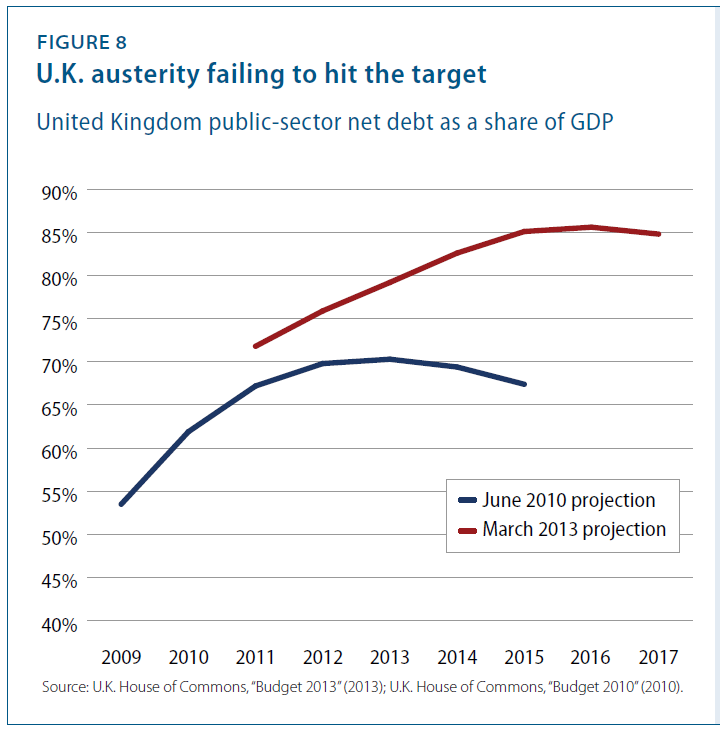

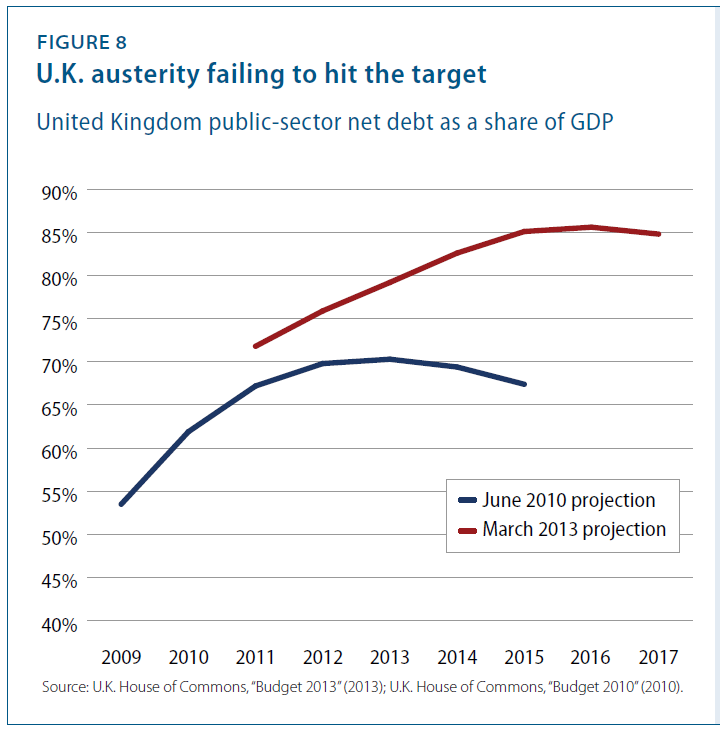

Pilkington now sees Labour leaders positioning themselves closer to the ruling Conservatives’ pro-austerity stance. That may or may not be a shrewd political move, but in terms of policy, what recent economic events have made austerity look more attractive? The UK just posted a blistering GDP growth number of 0.3 percent (thus barely avoiding its third slide into recession in the last five years), and as Michael Linden illustrates (pdf) with the figure below, since Cameron’s austerity measures were imposed in 2010, the UK’s projected debt-to-GDP ratios have gone up instead of down. Assuming the goal was to reduce the debt ratio, and not simply reduce government spending for its own sake, austerity seems to be failing:

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 24, 2013

Whether it’s the terrible growth numbers in the eurozone (Eurostat), the revelation of spreadsheet errors in everyone’s favorite debt disaster study (for some of the non-spreadsheet-based problems with the Reinhart-Rogoff approach, see this 2010 working paper), or the fact that the US federal deficit is on track to shrink to a measly 2.1 percent of GDP in two years (CBO report here), the past couple months have offered up some embarrassing and inconvenient news for those who continue to push for austerity.

Nonetheless, we’re unlikely to see any of this dramatically alter the budget debate, and the key to understanding why is to appreciate that there is a significant constituency among austerity supporters for whom most of this data is irrelevant. It’s not just that this information isn’t likely to persuade them, but that for a certain species of austerian, it couldn’t possibly. After four years of fiscal fear-mongering, it has become clear that for some ostensible austerity supporters, it was never really about the deficit.

With last week’s updates, the CBO now predicts that the budget deficit will fall to 2.1 percent of GDP by 2015. If that number means nothing to you, consider that the original Bowles-Simpson plan — the standard by which budget seriousness is measured in the press — called for a 2015 deficit of … 2.3 percent of GDP. Pikers.

Yet, revealingly, there are some deficit hawks who are treating the rapid shrinking of the deficit as bad news — and not for the Keynesian reason that this indicates the government is failing to do its part in supporting the economy, as Bernanke stressed in his remarks yesterday, but because the disappearing deficit is easing congressional pressure to pass “entitlement reform” (which, as we’ll see below, does belong in scare quotes).

And lest you think this is all about concern for the long-term deficit, note that one of the reasons projections of future deficits have been falling is due to a slowdown in the growth of healthcare costs. If this slower rate of cost growth maintains itself for any significant period of time, the story we’ve been hearing with regard to the long-term budget changes dramatically. Here, according to the CEA‘s Economic Report of the President, is what Medicare spending will look like over the long term if the more recent trend in healthcare costs sticks: continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 15, 2013

That’s the implication of a James Pethokoukis post linked to here by Reihan Salam. Let’s assume for the sake argument that a federal budget surplus does emerge in 2015 (yesterday’s CBO report projected the 2015 deficit would be a mere 2.1% of GDP). Salam expresses concern that such a scenario would leave Republicans, who have been banging the austerity drum since inauguration day 2009, in a political and policy bind. It would allow Democrats to declare “mission accomplished,” as Salam puts it, leaving Republicans with no agenda.

One problem with this analysis is that it assumes the voting public would even recognize/concede the existence of a budget surplus. If you’ve been paying any attention to US public affairs, you’ll have observed that the realm of empirical fact is a fiercely contested battlefield (see warming, global). And on budget matters, as Dimitri Papadimitriou has pointed out, the battlefield is tilted in one direction: “The deficit has arguably gained the distinction of being the single most widely misunderstood public policy issue in America. Just 6% (6!) of respondents in a recent poll correctly stated that it had been shrinking, which has in fact been the case for several years, while 10 times more, 62%, wrongly believed that it’s been getting bigger.”

Now, it ought to be mentioned that no one should get any credit for a budget surplus in 2015 (or for a deficit as low as 2.1% of GDP, as the CBO predicts). Under current economic conditions, this would represent the continuation of an inexcusable fiscal policy error — and the reason it would be an error points to another problem with Salam and Pethokoukis’s political concerns. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | April 5, 2013

Here are today’s big pieces of economic policy news: (1) net job creation in the month of March (+88,000) was too low to keep up with population growth; (2) the president’s budget proposal will reportedly include cuts to Medicare and Social Security (or as the latter will be described in most newspapers, “adjustments to the way inflation is calculated for the purposes of determining Social Security benefits”).

These two items may seem unrelated, but in reality they form the basis of an unhappy remarriage. continue reading…

Comments

Greg Hannsgen | March 29, 2013

An update on some developments on the fiscal-trap front: After a Levy brief on fiscal traps was issued in November, events continue to bear out the fears expressed therein that budget cuts and tax increases being implemented in Europe and the US would lead to disaster. For example, recent news coverage of events surrounding the announcement of the UK budget confirm that the trap can hit nations that possess their own currencies, particularly in a region such as Europe where recessionary forces are dominating at the moment. Martin Wolf notes that owing to disappointing growth figures, the UK deficit surprised again on the high side. As the fiscal-trap theory asserts, governments implementing austerity policies have run into unexpectedly low growth in their attempts to reduce government debt.

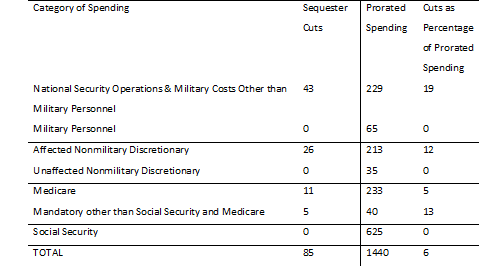

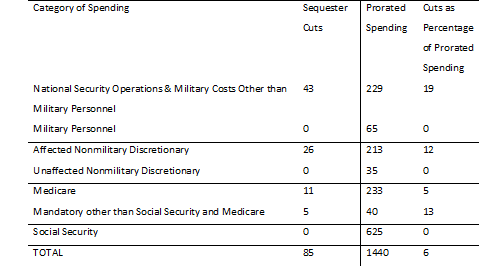

Meanwhile, despite the warnings of macroeconomists, including those here, the austerity measures that together make up the fiscal cliff in the US were only partly averted. Among these policy changes are the loss of the 2-percent partial payroll-tax holiday and the sequester cuts to discretionary spending. The latter unfortunately went into effect at the beginning of this month, following a two-month Congressional reprieve. Based on unofficial data from the Bipartisan Policy Council in this New York Times article, which are similar to those in a recent and more detailed CBPP report, the cuts for the remainder of the fiscal year are large as a percentage of planned spending, as seen in Table 1:

Dollar amounts shown in billions.

continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | March 28, 2013

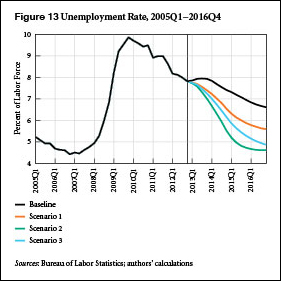

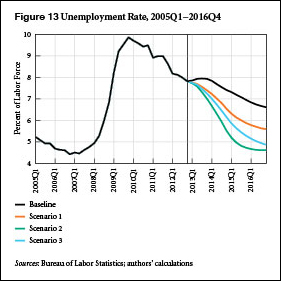

How much fiscal stimulus would the government need to inject into the economy over the next two years in order to get the unemployment rate into the 5.5–5.9 percent range? In their newest strategic analysis, Dimitri Papadimitriou, Greg Hannsgen, and Michalis Nikiforos provide us with some harrowing answers.

The authors lay out a scenario (“scenario 3” in the analysis) featuring some favorable macroeconomic tailwinds in the form of higher private sector borrowing and increased exports. As they explain, such developments are not entirely unlikely (and policy changes could help contribute to such an export boost). Nevertheless, even in these relatively rosy circumstances the government would need to pitch in a spending increase of 6.8 percent* (after inflation) in each of 2013 and 2014 to bring the unemployment rate below 6 percent by the end of 2014. That would amount to a stimulus program worth around $600 billion over the next two years. Without these tailwinds from private sector borrowing and exports (“scenario 2”), spending would need to increase by 11 percent per year — or roughly over a trillion dollars of stimulus over two years — in order to bring unemployment down to around 5.5 percent.

As the authors note, Washington is not in the mood for a trillion-plus-dollar stimulus program, or a program half that size. Congress has consistently rejected a mere $50 billion for infrastructure repair. If anything, the policy challenge of the moment is to temper the zeal for cutting spending. Moreover, 5.5 percent unemployment is arguably still shy of what we ought to consider “good enough.” This level is around a full percentage point above where we were before the recession hit in 2007. In other words, even if this Congress were to approve a stimulus package larger than the 2009 Recovery Act (ARRA) — which is unimaginable at this point — we would still not be back to pre-recession unemployment levels after two years (or even four years, as the strategic analysis demonstrates).

While we’ve been focused on phantom budget menaces derived from assumptions about the state of medical technology in 2080, the jobs crisis has continued to ruin real lives. Without a dramatic turnaround in our fiscal priorities, it will continue to do so for years to come. It’s become pretty clear that the actual needs of this economy far outstrip what the political system is willing to deliver. (The authors actually favor direct job creation, in the form of an employer-of-last-resort policy, but they suggest that this is currently even further outside the realm of the politically possible as compared to traditional fiscal stimulus.)

Assuming no further stimulus is possible, the “best case” scenario over the next four years might be to merely hold off any new attempts at grand bargains or further budget cuts; to maintain the miserable status quo on the budget. In that case, as the figure below illustrates (the authors’ “Baseline” forecast represented by the black line), unemployment would still be above 7 percent in two years, and above 6.5 percent by the end of President Obama’s term in office (which, as the authors point out, is still in excess of the threshold at which the Fed would consider tightening monetary policy).

The full analysis can be downloaded here.

* Specifically, the increase applies to “real government purchases of final goods and government transfers to the private sector.”

Comments

Michael Stephens | February 22, 2013

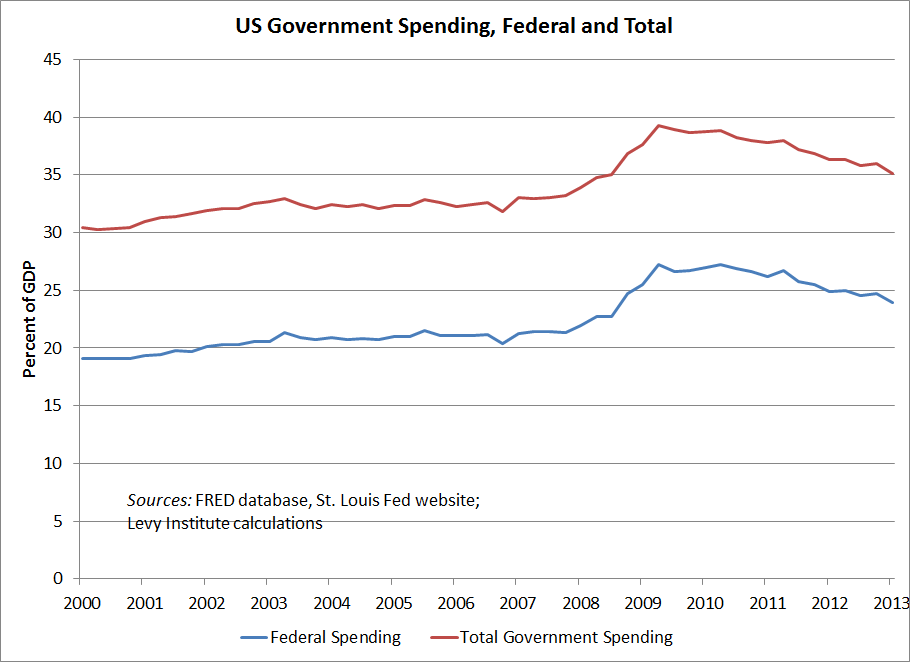

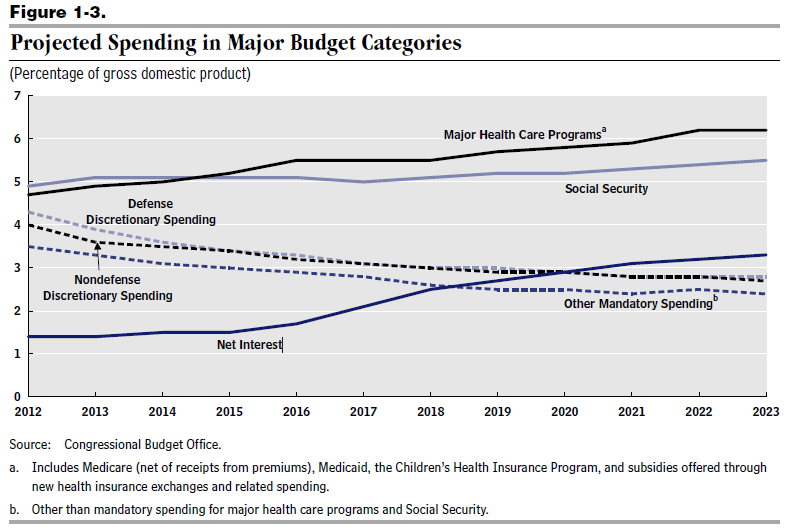

The Congressional Budget Office’s latest report on the budget outlook revealed (perhaps unintentionally) that fixating on Congress and the President as the central players in the federal deficit drama is a mistake. According to the CBO, the path the federal budget deficit will follow over the next 10 years is just as much (if not more so) a question of Federal Reserve policy.

Here’s CBO’s latest 10-year outlook for the federal budget:

As you can see, the fastest rising category of spending is not “Social Security,” or even “major healthcare programs,” but rather “net interest,” which CBO projects will grow from 1.4 percent of GDP to 3.3 percent of GDP by 2023 (“a percentage that has been exceeded only once in the past 50 years,” they note). continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | February 19, 2013

A couple of links worth sharing on the politics and policy of the budget debate.

First, the Wall Street Journal reports that Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles are coming out with a new deficit reduction plan, worth $2.4 trillion. If it’s anything like the last plan, every lawmaker will claim to love it, journalists will assume its goodness as a fact more established than the shape of the earth, no one will have a clue what’s in it, and it will go nowhere.

The details have not yet been released, but one initial question you might have is this: where does that $2.4 trillion number come from? Have they taken their original deficit reduction target from 2010 ($4 trillion) and subtracted the amount of budget savings already achieved ($2.5 trillion)? Apparently not. Has the deficit picture worsened since 2010? Quite the contrary. If you look at healthcare alone, the government is now set to spend almost $1 trillion less over the next decade than what was expected when Simpson and Bowles were coming up with their plan. If their new plan takes these recent developments into account, it’s not clear how. The question remains: why this number?

We’ll have to wait to hear what the justification is (if there is any). Perhaps this is an issue of different budget windows, but it’s also possible we’re looking at another example of the asymmetry between deficit hawks and deficit doves (or owls) when it comes to budget targets. For the dovish, the budget math is reasonably simple: the right level for the deficit is whichever one will bring us back to full employment (likely a higher deficit than we have now). For the hawks, it’s not quite as clear. Stabilizing the public debt as a percentage of GDP (at 73 percent), the administration’s target, is apparently not sufficient. If someone is consistently specific about means (in this case, cut spending on programs that benefit the elderly in such a way that benefits are reduced; shrinking healthcare providers’ profit margins doesn’t count) but a little vague about the ends, you should start to consider the possibility that their means really are their ends, and vice versa.

Second, Dan Kervick at New Economic Perspectives argues that the debate over healthcare costs is very poorly framed as an issue of budget deficits: continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | February 15, 2013

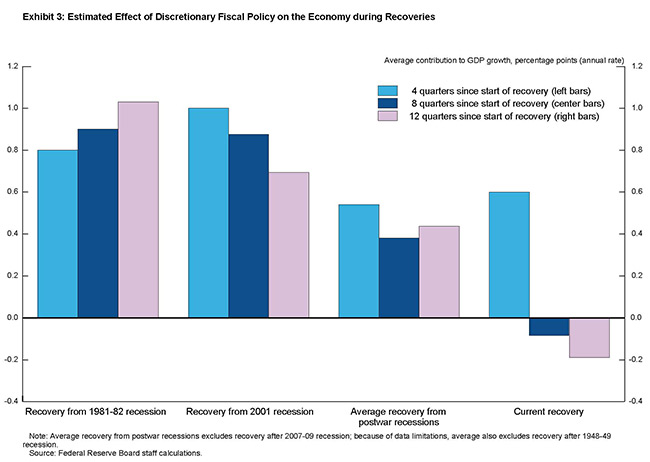

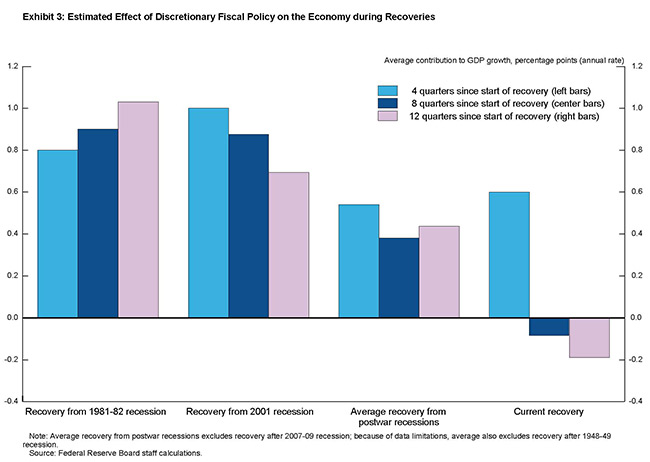

Here’s yet another way of representing the fact that to the extent the United States has a “spending problem,” it is a problem of too little spending. From a speech by Janet Yellen, Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve:

… discretionary fiscal policy hasn’t been much of a tailwind during this recovery. In the year following the end of the recession, discretionary fiscal policy at the federal, state, and local levels boosted growth at roughly the same pace as in past recoveries, as exhibit 3 [below] indicates. But instead of contributing to growth thereafter, discretionary fiscal policy this time has actually acted to restrain the recovery. State and local governments were cutting spending and, in some cases, raising taxes for much of this period to deal with revenue shortfalls. At the federal level, policymakers have reduced purchases of goods and services, allowed stimulus-related spending to decline, and have put in place further policy actions to reduce deficits.

On this issue, the conventional wisdom is so far from the truth that it’s difficult to figure out how one might begin persuading anyone who isn’t acquainted with the data (lest one appear insane). It would be one thing if current fiscal policy were merely in line with past expansionary practices in the wake of recessions (even arguing that much will get you some raised eyebrows and uncomfortable coughs). But the dismal truth is that, after 2009—when discretionary fiscal support was a hair above the postwar average but well below the expansionary stimuli under Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush—the combined federal/state/local government fiscal response broke dramatically with the postwar pattern, in a display of record-breaking stinginess. To borrow loosely from H. L. Mencken: if you want government to rein in its spending, you’re getting it good and hard.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis