Some New GDP Numbers–And 3 Trendlines

We end the week with news of only modest economic growth, but also with a set of revised data that does not seriously worsen the economic outlook. Today the Bureau of Economic Analysis announced the release of an advanced estimate of 2nd quarter GDP, as well as revised data for 2009Q1 through 2012Q1. Their press release notes that:

“Real gross domestic product—the output of goods and services produced by labor and property located in the United States—increased at an annual rate of 1.5 percent in the second quarter of 2012, (that is, from the first quarter to the second quarter), according to the “advance” estimate released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In the first quarter, real GDP increased 2.0 percent.”

An article from the FT points out that consumption grew by 1.5 percent, while government spending at all levels of government fell by 1.4 percent. Leaving the drop in government spending out of the calculation would raise the overall growth rate to 1.8 percent per year, or .3 percent higher than the actual figure released today.

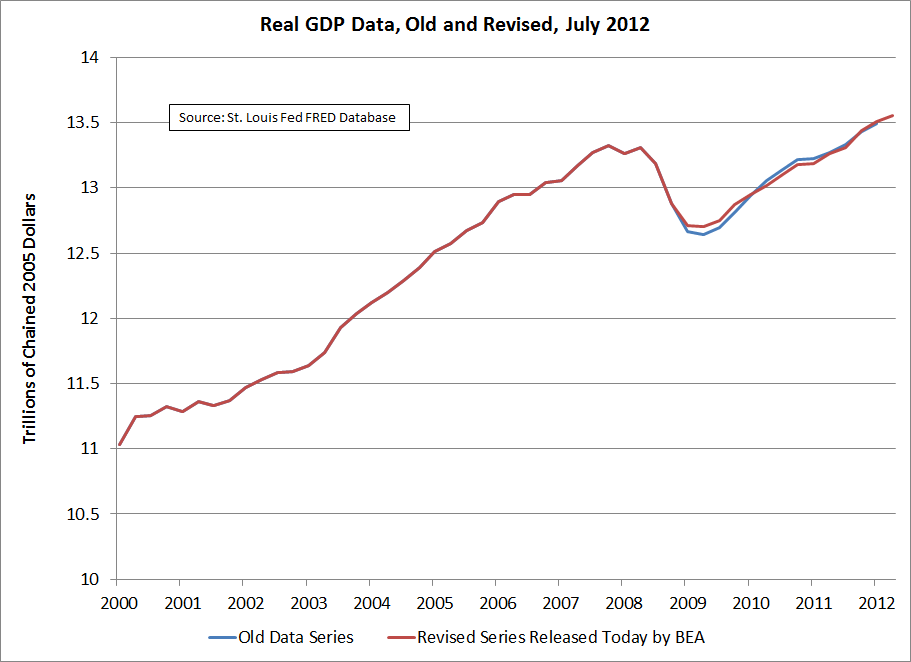

Here is a graphical comparison of the old and new data series:

As the figure shows, the new data series implies that the fall in real GDP during the 2007–09 recession was not as deep as previously believed, though this difference is rather small. (Note: This earlier FT article mentions some of the reasons the GDP series needs to be revised, and well as some of the anticipated policy implications of today’s data release.)

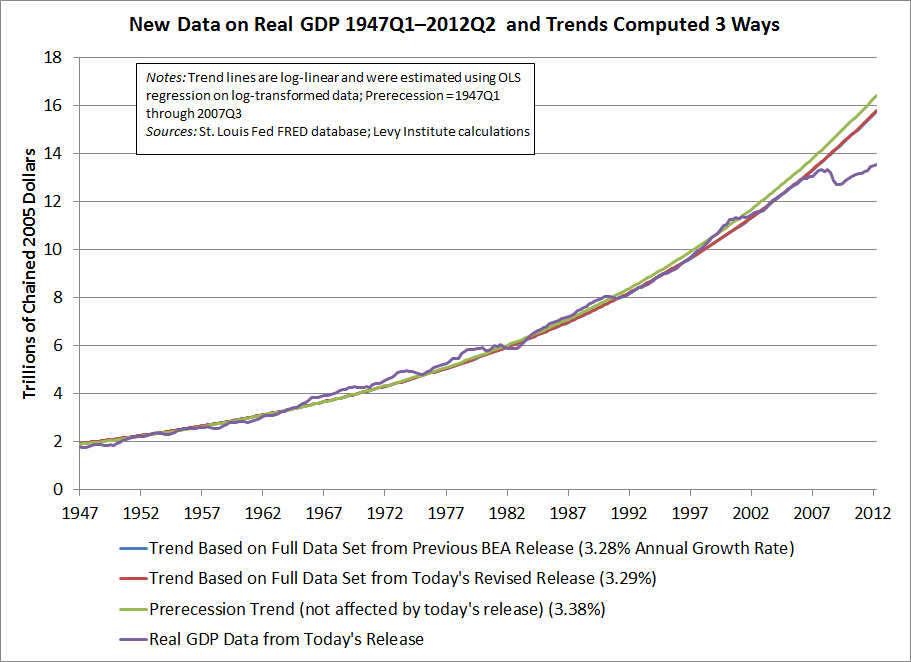

Also, the revisions make only a slight difference in an estimated trend line for all the data, as seen in the figure below, where the blue line is hidden behind the red one. However, these trend lines are much different from a similar estimate constructed using prerecession data (1947Q1–2007Q3) only, which is also seen below.

The continuing weakness of the actual GDP data compared to the prerecession trend line provides further support to the notion that the economy has a lot of extra room to grow. In other words, such a sharp drop in economic activity relative to an existing trend is an indication that private-sector output can recover to a great extent without straining supplies of labor and most other resources. Hence, economic stimulus designed to increase aggregate demand is in order, as we have argued for some time. The reported decline in government spending is of some concern indeed.

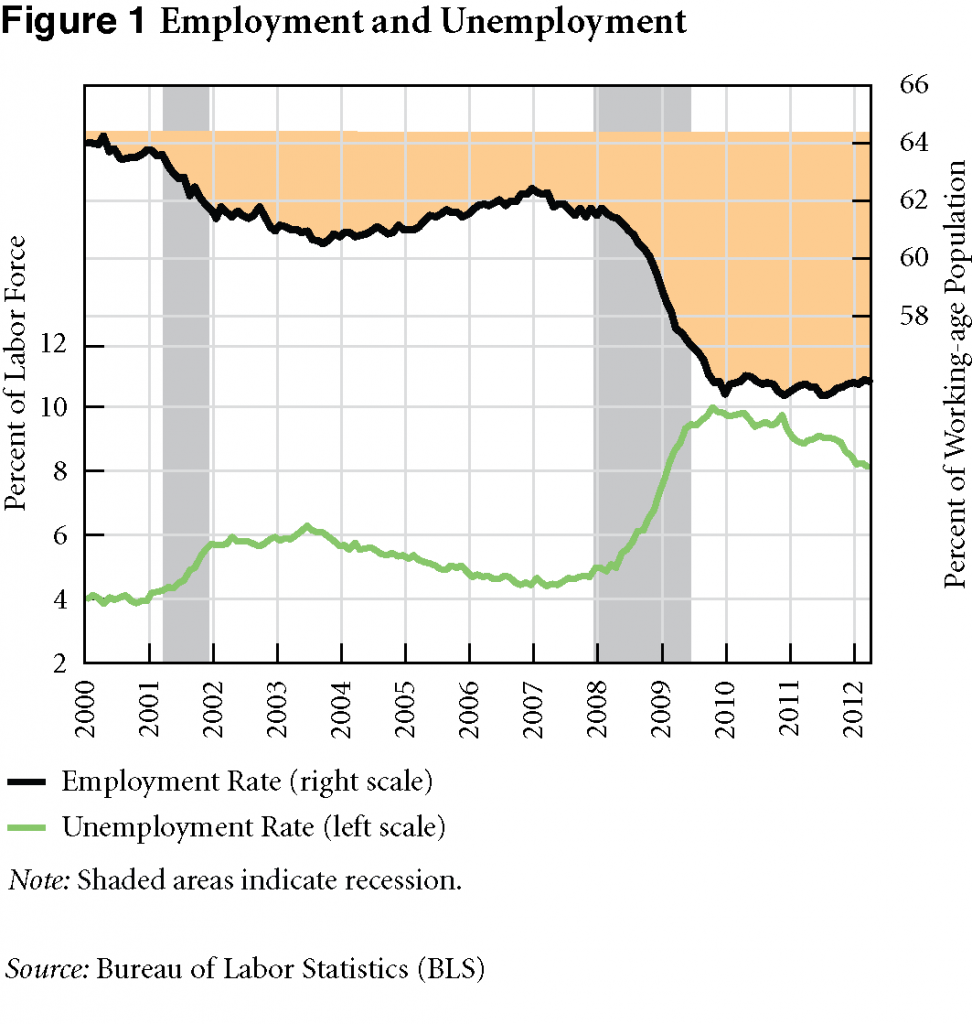

These numbers of course do not constitute a good measure of national well-being, but at their recent levels, they are symptomatic of an economy experiencing a prolonged period of high unemployment rates, which can contribute to many other social and economic problems.

Postscript, July 27: Interesting, same-day posts by New York Times bloggers point out that the revised data reveal a shrinking government sector and analyze the effects of the revisions.

ShareThis

ShareThis