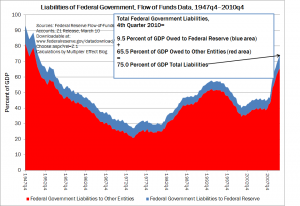

(Clicking on picture will make it larger.)

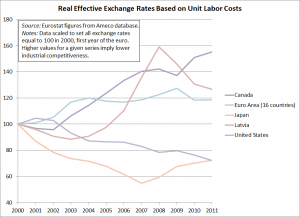

Floyd Norris has an interesting column in this morning’s New York Times. Earlier this week, I was getting ready with some observations similar to his, though I am sure I could not have done as good a job as he has in getting across the gist of the problem and presenting some evidence. Essentially, Norris shows that since the introduction of the euro in 2000, products from the countries now in fiscal crisis have lost competitiveness relative to German products in international markets. Norris presents data on competitiveness. His data is similar to the series depicted in the chart at the top of this post, but the data above are real exchange-rate indexes. The lines in my chart compare the competitiveness of various economies’ exports, taking into account not only differences in unit labor costs but also the values of their currencies relative to those of their trading partners. Norris’s graph and my own feature data from different economies.

Norris’s point is that Germany is an big exporter partly because it has reduced labor costs relative to its competitors. Meanwhile, according to Norris’s theory, the peripheral countries of Europe, such as Greece, Ireland, and Portugal, have become less competitive, as their labor costs have risen relative to those in Germany and other “core” European nations. And because of the common currency, these higher-cost countries cannot use a devaluation to regain competitiveness.

As all acknowledge, the issues involved are complex. One key critique of the current approach to policy embodied by the European Central Bank and European Union rules is that this game clearly has winners and losers, mostly the latter. Norris’s graphs show increasing trade deficits in Italy, France, Spain, as well as the aforementioned troubled economies. While there is no reason that all countries must lead at once, someone, in either government or in industry, must hire workers to produce goods or services if employment is to be increased. Current bailout agreements and big debts are leading to drastic cuts in government employment and wages, even as they bring protests from opposition parties in countries called upon to help fund bailouts. This has contributed to a situation in which unemployment is extremely high in much of Europe, while all are focusing on the need to cut government spending, seemingly ruling out new or enlarged Keynesian public works programs.

However, it must also be said that the notion of cutting wages and benefits is also hard to swallow for most Europeans. The countries currently in deep crisis are not known as having high real wages for rank-and-file workers. Also, wage cuts have a tendency to undermine domestic demand for consumer goods, but cannot accomplish the complex task of making a country’s exports competitive in foreign markets. This is doubly true at a time when so many countries are attempting to cut production costs at the same time. Wage cuts do not reduce standards of living if they are accompanied by cuts in domestic prices. However, deflations have a tendency to make it more difficult for consumers and governments to pay off debts, which are mostly for a fixed amount of euros. Also, most deflationary policies tend to reduce economic growth and are appropriate only when the economy is booming and inflation is high. This is one of the key problems with the “new Keynesian” view—held by many economists—that rigid or “sticky” wages set in union contracts, etc., are a key cause of unemployment during business-cycle downturns.

There is much discussion of these issues on the web these days. Jeffrey Sommers and Michael Hudson, who holds an appointment at the Institute, have pointed out in a number of articles this year (such as this one) that the Latvian economic-policy model, which involved spending cuts and other efforts to regain competitiveness, has not been as popular in Latvia itself as some commentators have implied. Moreover, recent policies in Latvia have led to large-scale emigration, while failing to bring strong economic growth, in the aftermath of a 25 percent fall in output. (Latvia’s real exchange rate is among those shown in the chart above.) Charles Wyplosz analyzes data similar to those shown above and in Norris’s New York Times column and comes to the conclusion that differences in labor costs are fairly small—especially considering the likely accuracy of the data—and are not crucial to current problems in Europe. Last month, Alejandro Foxley of the Carnegie Endowment offered a more sanguine view than Sommers and Hudson of events in Latvia, while attributing many European problems to the rapid deregulation of financial markets and the rush to the adoption of the euro. He sees the latter process as having brought about an unsustainable boom in financial investment, property values, and consumption spending in many currently struggling economies.

We disagree with many of the arguments in these articles. They describe a situation that differs in many ways from the current one here in the United States. But the authors’ analyses are helpful to economists like me who lack intimate knowledge of the countries involved and their economic issues. While European countries should certainly not attempt to reduce wages across the board, policymakers there are in a position in which issues of excessive public debt are very real. Hence, the lessons for the United States, with its dollar-printing machine, are not always straightforward. But also, as the figure above suggests, the United States also has little reason to worry about excessive wages relative to those in the average industrialized country.

Update, April 25, approximately 8:10 am: I have revised the chart to include Canada, a major trading partner of the United States. Also, I made minor clarifying edits to the text used in the post and figure.

ShareThis

ShareThis