In advance of this week’s Ford–Levy Institute conference in Athens, Greece (Nov. 8–9), Jörg Bibow gave an interview with George Papageorgiou, senior editor of newmoney.gr, on the role German policy has played (and still plays) in generating and exacerbating many of the problems plaguing the eurozone periphery — something Bibow was warning about back in 2005 (see here, for instance). He also addressed where the eurozone needs to go from here, touching on a plan for a Euro Treasury he’ll be discussing at the Athens conference.

The English text of the interview follows (Greek version here):

You have been critical of German policy. How does it really affect the rest of Europe? In what ways does it cause harm to the peripheral economies?

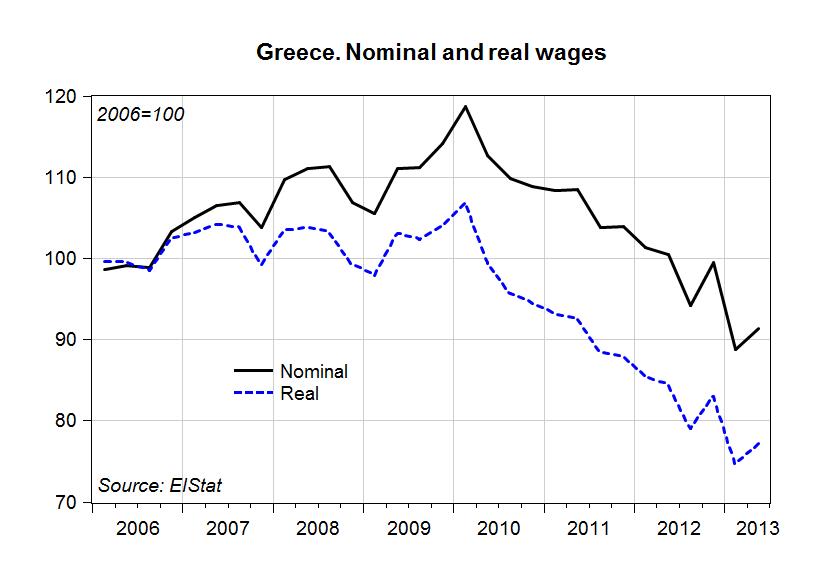

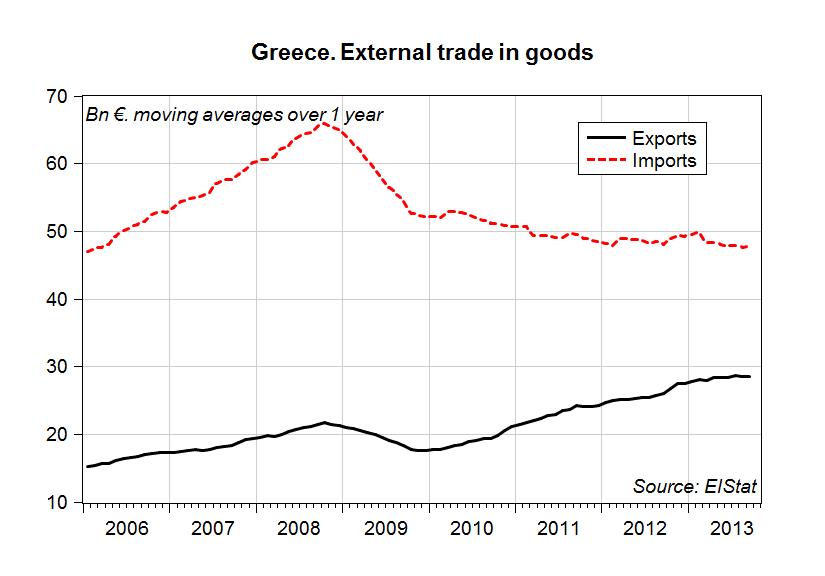

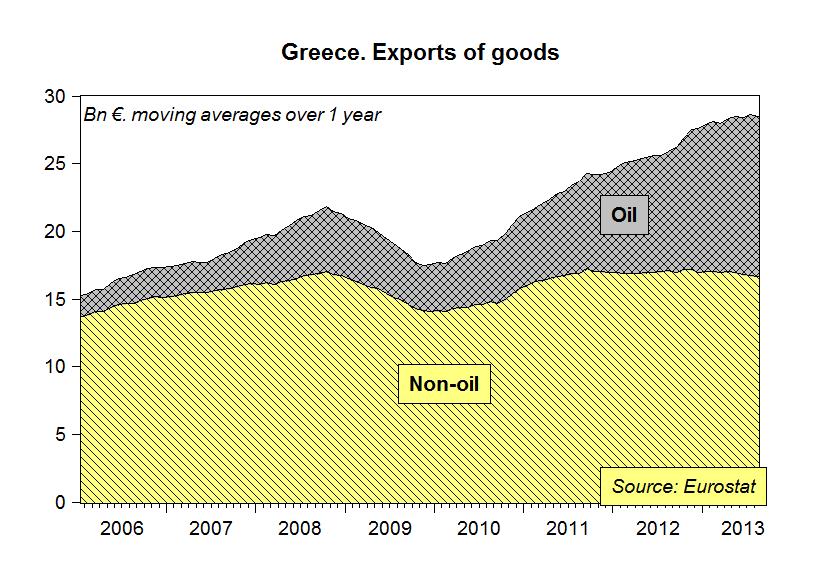

Yes, indeed, German policy bears foremost responsibility for the euro crises and German policy is key to Europe’s future. Germany is Europe’s largest economy. For that reason alone whatever happens in Germany inevitably significantly impacts the eurozone economy. For instance, when Germany prescribed itself an extra dose of wage repression and fiscal austerity in the early 2000s, this had rather fateful consequences for the currency union. For one thing, stagnant domestic demand in Germany constrained its euro partners’ exports to Germany. For another, stagnation in Germany provoked some degree of monetary easing from the ECB, monetary easing which was both too little for Germany but too much for the euro periphery where wages and domestic demand were thereby propelled further. In other words, Germany undermined the ECB’s “one-size-fits-all” monetary policy stance. This happened alongside cumulative divergences in intra-area competitiveness positions, current account imbalances and the corresponding buildup in foreign asset and debt positions. Together this meant that the currency union was going to face trouble as soon as those imbalances would start to unravel. I started warning of these developments in 2005, but the euro authorities were sleeping at the wheel for many years to come.

This is the background to the still unresolved euro crisis, which is primarily a balance-of-payments and banking crisis that only became a sovereign debt crisis as a consequence. Adding insult to injury, the crisis has left Germany in the driver’s seat in eurozone policymaking. Germany punches above its weight in current policy debates. Unfortunately, in misdiagnosing the true nature of the crisis, Germany’s policy prescriptions have focused on nothing but fiscal austerity and structural reform. The consequences are proving a disaster for Europe. In particular, since Germany refuses to adjust its massive external imbalance and continues to have very low inflation, the ongoing rebalancing process inside the currency union is proving deflationary for everyone else. Essentially, as average eurozone wage and price inflation has fallen to extremely low levels, euro crisis countries are forced into debt deflation. Predictably, the wreckage is truly enormous. Policies and consequences are akin to what U.S. President Hoover and German Chancellor Brüning attempted in the 1930s. As we know, this sad experiment in macro policy folly gave the U.S. FDR, the New Deal, and Social Security, while outcomes in Germany were far less benign. It is as yet unclear which path Europe will take this time; the constructive or the destructive one.

What drives then Germany’s current policy? Doesn’t its leadership recognize the danger it poses for the future of the eurozone?

Confusion, a load full of ideological baggage, and short-sighted vested interests, I suppose. Apparently the German authorities do not understand the futility of their favored policies. My reading is that they have never quite understood that Germany could only succeed with its peculiar economic model in the past because and as long as its key trading partners behaved differently. Today Germany is forcing Europe to become like Germany. The trouble is of course that not everyone can be super-competitive and run perpetual current account surpluses at the same time. Somehow the German authorities are stuck in a deep ideological hole on this issue – and they keep on digging.

If Germany continues practicing its current policies, what would be the most likely outcome? Will we head towards the dissolution of the eurozone or with the permanent two- or even three-tier Europe and with the periphery in a quasi colonial situation? continue reading…

ShareThis

ShareThis