People often say that the problem in Greece is profligacy. Greece, the story goes, is a nation living beyond its means. Reading the press, in fact, one gets the impression that Greeks must enjoy one of the highest standards of living in Europe while making the frugal Germans pick up the tab.

In reality, Greece has one of the lowest per capita incomes in Europe, much lower than the Eurozone 12 or the German level. Furthermore, the country’s social safety net might seem generous by US standards but is truly modest compared to the rest of Europe. As to borrowing, Greece is far from unique in its level of overall indebtedness as a percentage of gross domestic product.

So what’s the real problem? It all started when Greece embraced the Euro, which some saw as the country’s salvation. But as is so often the case, what once seemed a strength turns out to be weakness. The same might be said of Greek social programs; once seen as a pillar of the state, in hard times they automatically swell government deficits.

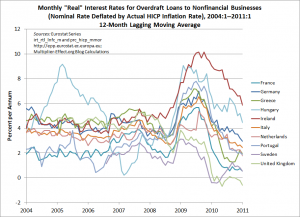

Remember that as Europe slid into recession, tax revenue fell and social transfer payments (such as unemployment benefits) rose, opening a larger gap between tax receipts and spending. The same thing happened in the United States. But the United States controls its own monetary policy. In Greece, which is stuck with the Euro, yawning deficits began to worry investors. With borrowing costs soaring, the country has embarked on an austerity program. Unfortunately, If the government lowers its deficit during a recession through spending cuts or tax increases, the strategy is destined to fail.

Cutting wages and pensions, as the recent presidential decree declared, which is a large part of the imposed EU/IMF plan, or raising taxes for that matter, will only make budget deficits bigger by lowering national income and tax revenue. This will mean lower effective demand, which will exacerbate the already bad unemployment situation and potentially lead to more civil disturbances. Some analysts estimate that unemployment will increase by 6 percentage points as a result of the austerity package.

More importantly, Greece continually imports more than it exports, and its firms and individuals spend more than they save (much like some large countries in North America that I can think of). Now, any country’s current account deficit plus its private sector deficit equals its government deficit. During recessions the private sector cuts spending and tries to save more. This automatically takes the government further into deficit territory as social programs grow and taxes fall. Bear in mind that when the current account goes into a deficit, which is a leakage out of private sector income, it means that unless the government deficit rises by the same amount, the private sector’s saving will fall. In the context of Greece’s high current account deficit, its private sector has been running a deficit for the past decade.

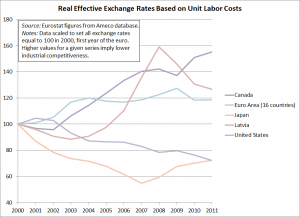

Even though the macroeconomic accounting identity linking the sectoral balances is not a theory, it is a good way to analyze policy proposals. When some analyst says that Greece needs to lower its budget deficit to 3% of GDP, then looking at the sectoral balances one must ask, what will need to happen to the balances of the other sectors for this to take place? For example, in 2009, the Greek current account deficit was about 10 percent of GDP. The budget deficit including swaps was about 13 percent of GDP allowing the private sector to save at 3 percent of GDP. Without the option of currency depreciation, it is hard to imagine that Greece can boost its exports (and/or reduce imports) to the point of a balanced or surplus trade account—a swing of 10 percent of GDP. If the budget deficit is to be lowered to 3 percent of GDP to comply with the Eurozone’s Stability and Growth Pact limit, firms and households will need to run a deficit of 7% if there is no change to the current account balance.

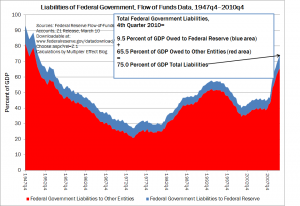

In other words, without a massive adjustment of its current account balance, the austerity plan can succeed only if the country replace public deficits with private deficits, and private debt buildup at this rate would certainly be unsustainable. It looks like Germany’s disciplined fiscal policy has been able to accomplish precisely this. Low levels of German government debt have been offset by high levels of private debt—arguably, more unsustainable than public debt. Ireland, Spain and Portugal are in a similar situation. Greece, on the other hand, has allowed its private sector to operate with somewhat lower levels of debt as the government’s deficit has risen relatively more. Indeed, the “profligate” Greeks have less private debt than that of their neighbors—which could place them in a better situation to withstand this crisis.

Still, financial crises and recessions inevitably lead to larger public deficits and debts. The private sector deleveraging that occurs in recession must be accompanied by public sector leveraging unless the current account moves to the surplus side.

Most developed countries, including the United States, United Kingdom and Japan, are in a similar situation in terms of their deficit and debt positions. But they have their own currencies. In the Eurozone, the issue is that the Stability and Growth Pact requirements are not rooted in any sensible theoretical arguments or empirical evidence. Countries have different export profiles and private-sector saving rates, and these influence the public sector’s balance. For European governments to be able to comply with the Stability and Growth Pact requirements at all times, they would need to abandon most of their social protection policies so that spending on the safety net does not rise in recessions. This would be counterproductive, to say the least. The bottom line is that the non-discretionary nature of Greece’s deficit does not leave many options for the government during bad times.

ShareThis

ShareThis