Jörg Bibow was recently interviewed by CJ Polychroniou in Kyriakatiki Eleftherotypia (Κυριακάτικη Ελευθεροτυπία).* An English transcript of the interview follows:

Since Mario Draghi’s announcement last fall that the ECB will intervene with the purchase of government bonds, the euro crisis is in a state of relative calm. Is it over? And if not, what developments could make the crisis resurface?

Yes, Mr. Draghi’s promise of ECB support for government bond markets seems to have calmed fears of an imminent euro breakup, at least for the time being. That does not mean the euro crisis is over though. Not at all, as the underlying problems remain largely unresolved. Liquidity can buy time but it cannot solve the imbalances inside the euro area and related debt overhangs that are the deeper cause behind the euro crisis. It is important in this context that the ECB promise is for conditional support. As liquidity support comes along with mindless austerity and asymmetric adjustment pressures imposed on debtor countries, debt problems are bound to get worse rather than better. Markets are currently in complacency mode about these prospects. The crisis may resurface at any time.

In several of your studies, you point to Germany as the main culprit behind the euro crisis. Why is that?

Yes, Germany is the culprit. Being the largest economy in Europe, Germany’s performance and policies inevitably impact Europe. In the currency sphere Germany is also Europe’s traditional anchor of stability. As a result, the policy regime of Economic and Monetary Union agreed at Maastricht is largely of German design, based on the Bundesbank success story and deutschmark stability. It was not understood that the pre-EMU success of the German model of export-led growth required that other countries behaved different from Germany. Germany’s traditional two-percent price stability norm stimulated export-led growth as long as Germany’s trade partners had higher inflation, as such a differential would give rise to cumulative German competitiveness gains over time. Exporting the German model to Europe and requiring everyone to abide by the two-percent stability norm was therefore begging for trouble. Exports would no longer fulfill their traditional role as growth engine. Confronting high unemployment, Germany therefore departed from its own stability norm by prescribing itself flat wages. German wage repression—joined by mindless fiscal austerity—turned Germany into the “sick man of the euro,” suffering from protracted domestic demand stagnation. However, German competitiveness once again improved over time, this time inside the currency union. At the same time, given Germany’s size, the ECB’s monetary policies became too easy for countries with stronger domestic demand dynamics. Herein rests the source of the currency union’s internal imbalances and consequent crisis. German banks sponsored the boom in the so-called periphery serving as the vent for German trade surpluses.

You have argued that a euro country that runs up surpluses must lend or transfer its surpluses to the deficit-running euro countries. Germany and the other “northern” euro countries will never accept such a condition, so what are the implications of this for the future of the eurozone—a permanent fixture between a metropolis and satellite?

In pre-crisis times liberalized private capital flows permitted soaring intra-area trade imbalances. While Germany’s foreign asset position improved markedly, in the deficit countries, this meant a corresponding rise in external indebtedness. Internally, these debts were actually largely private debts, with Greek public debt developments as the outlier. At some point the markets woke up, and private capital flows dried up or even reversed. The irony is that since Germany cannot have perpetual export surpluses without bankrupting its partners, it is bound to end up paying for its über-competitiveness by means of fiscal transfers. The German authorities refuse to understand this accounting logic. They also decline to recognize that wrecking their debtors’ economies and driving them ever deeper into debt does not really improve the creditor’s position either. If Germany does not want Europe to be a transfer union it should end policies that make such a transfer union inevitable.

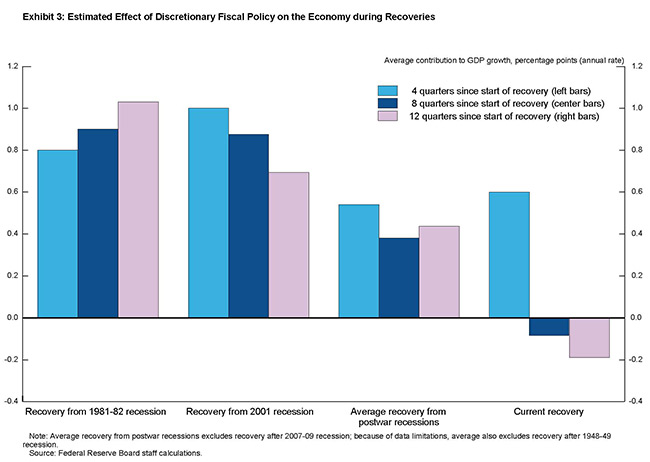

The IMF has admitted twice that it miscalculated the negative impact of the austerity measures on Greek growth because it misjudged the impact of the fiscal multiplier. But isn’t it the case that the IMF never paid much attention to the multiplier, anyway, considering it to be a Keynesian obsession? continue reading…

ShareThis

ShareThis