A New Collection of Minsky’s Work

Hyman Minsky is probably best known for his work on financial instability and financial reform, but he also wrote extensively about how to address the persistent problem of all those left behind by our increasingly financialized economy; about how to design policies that would put an end to income poverty in the midst of plenty. Despite the fact that far more attention has been paid to his writing on financial fragility, these were intimately related issues in Minsky’s research, connecting the financial and “real” economies.

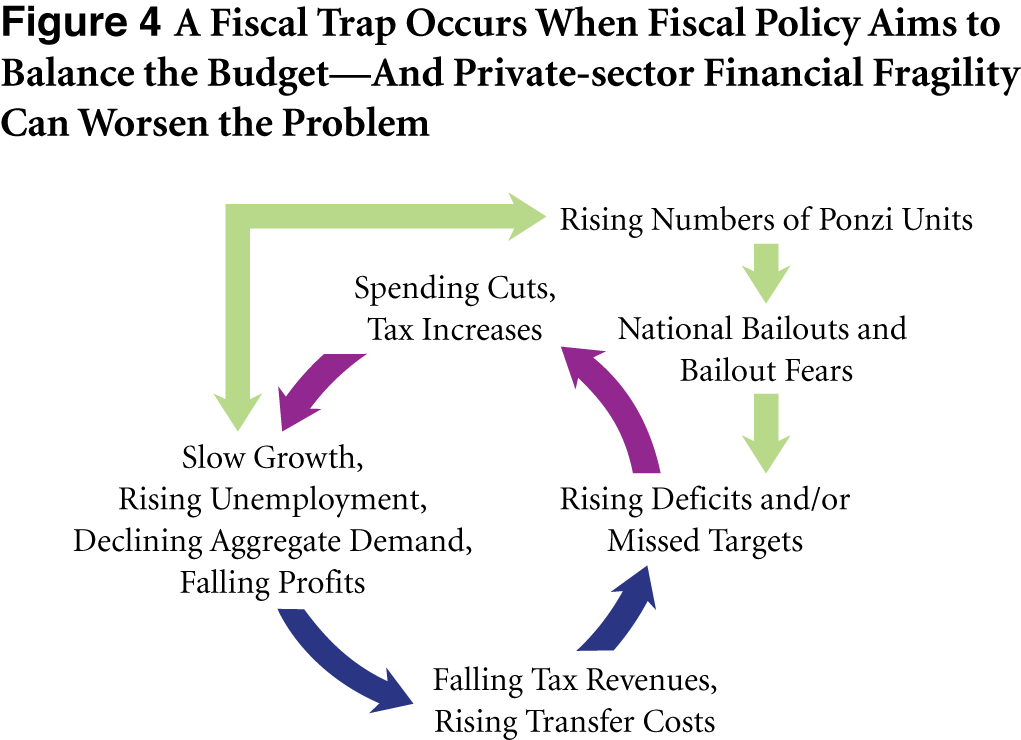

As with his work on finance, Minsky’s approach to poverty did not fit comfortably within the confines of the status quo. With “trickle-down” on one side, pure tax-and-transfer approaches on the other, and vague calls for retraining floating somewhere in the middle, Minsky found the conventional menu of policy options incomplete and inadequate (a menu that has changed very little over the last several decades). Calling for “upgrading” workers without ensuring there are enough jobs to go around is, as Minsky put it, “analogous to the great error-producing sin of infielders — throwing the ball before you have it.” What’s missing, he thought, is a commitment to ensuring that paying jobs are available to all who are ready and able to work; a commitment to “tight full employment.” The question is how to get there without sparking runaway inflation or inducing financial crises. Private markets, left to their own devices, aren’t going to get us there. For part of the answer, Minsky turned to a forgotten side of the New Deal: direct job creation.

In the interests of providing a more complete picture of Minsky’s intellectual legacy, the Levy Institute has published a collection of his central writings on poverty and full employment: Ending Poverty: Jobs, Not Welfare. The chapters span roughly three decades of Minsky’s writing and feature four never-before-published pieces. The earliest were written in the context of the “War on Poverty” of the Kennedy and Johnson years, but readers will find more than mere historical interest here. Minsky’s critiques of both the “neoclassical synthesis” and the welfare state hold up rather well. If anything, the material is even more relevant today, given our widening income inequality and chronic rates of long-term unemployment — and the fact that the battle against poverty, while not won, has largely been forgotten.

The paperback is now available on Amazon; the Kindle version will be appearing shortly.

ShareThis

ShareThis