Rachel! | August 24, 2011

The author is a Professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi. His views are his own.

An anti-corruption movement in India, run by a set of elites primarily from Delhi, has put poor Anna Hazare out in front and called itself a national movement. Their key demand is an anti-corruption citizen ombudsman bill, the Jan Lokpal Bill (JLPB), which would create an independent body investigating corruption cases, completing the investigation, and holding a trial within a specific time frame.

Is the Jan Lokpal Bill (JLPB) the path toward a corruption-free India? Presumably, if the answer were a straight forward “yes,” we would probably have had a JLPB by now. The founding fathers of this nation have gifted us a Constitution which laid the foundation for a vibrant democracy, a secular republic, and a federal structure. This strong foundation has not only kept this country together despite its adversities, but it has also been able to accommodate the needs and aspirations of people of diverse cultures, ethos, and religion with a fair degree of success. If the JLPB or a law of such nature were so important, certainly our founding fathers would not have deprived us of that perceived magic wand to keep India corruption-free. In the existing system itself there are sufficient institutional safeguards against corruption. Unfortunately, corruption continues to grow despite these safeguards. Public anger against corruption is justified, but Anna’s methods are not. continue reading…

Comments

Gennaro Zezza | August 9, 2011

While public discussion in the last several weeks has been absorbed by the debt ceiling saga, and in the coming weeks will probably focus on the S&P downgrade, employment (or lack thereof) is still a major problem. Our employment problem is one of the main factors contributing to a sizeable government deficit and growing public debt.

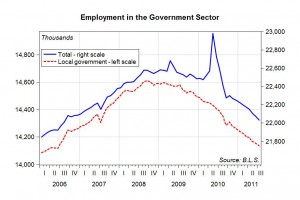

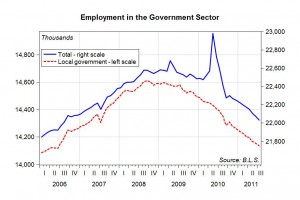

For all those who think that government has expanded wildly during the recession as a result of the fiscal stimulus, think again. The chart above shows that of the 7.3 million jobs lost since November 2007, 300,000 of those were lost in the government sector; more specifically in local government, which accounts for about 64% of the employment in the government sector. Local governments have to run a balanced budget, and when a recession hits and their tax receipts decline, they have to cut expenses—which means fewer jobs. If the federal government were to embrace similar balanced-budget policies, its ability to support a struggling economy would be severely curtailed. It would not only be unable to create jobs directly; it would struggle to even maintain its existing workforce.

The chart below shows one measure of the employment rate, computed as a percentage of the working-age population. This share rose in the post-WWII period with the increase in the female participation rate. It stabilized in the twenty years before the Great Recession at around 63%, dropped to 58% during the recession, and has remained roughly stable in the last ten months. To see what the prospects are for employment going forward, we have made some simple calculations. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 5, 2011

The BBC have broadcast a recent debate, dubbed “Keynes vs Hayek,” featuring Keynes’ biographer Lord Skidelsky. For anyone interested in an entry-level discussion of these competing policy approaches, and plenty of binge-drinking/hangover metaphors, it’s worth a listen.

* (Keynes, in reference to Hayek.)

Comments

L. Randall Wray | August 1, 2011

Bill Gross has weighed in on the debate about excessive sovereign debt, invoking a study produced by Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart that purports to show a negative relation between debt and economic growth. The “Maginot line” is a debt ratio of 90%, beyond which economic growth slows by 1%. Yet Mr. Gross does not consider the alternative: that high deficit and debt levels can be caused by plummeting revenue collection in the midst of an economic crisis. Neither Gross nor Rogoff and Reinhart offer any clear argument for their interpretation of the direction of causation, but the evidence this time around for the US is quite clear: it is the collapse of revenue that accounts for most of the growth of deficits. Unlike the case of Ireland (where the Treasury actually absorbed bank debt), the US bail-out of Wall Street has added virtually nothing to government deficits.

Further, like the original study, Gross lumps together countries with sovereign currencies (such as the US and the UK) and countries that abandoned currency sovereignty (the EMU members who adopted the euro, for example) or countries that never had it (those on specie standards).

The greatest fear surrounding growth of sovereign debt is that some point is reached where it becomes difficult or impossible to service the interest due. As that point is approached, markets demand ever higher interest rates, creating a vicious cycle. Greece knows that scenario all too well. But the case is different for the US, the UK, and even for Japan—as issuers of their sovereign currency they can make all payments as they come due. Involuntary default is not possible.

We are left with the possibility of a voluntary default, or a decision to “inflate away” the debt (something Gross discusses). The first of these certainly appears relevant, given the debate consuming Washington over the last months (although an agreement appears to have been reached, whether it will pass the House should still be considered an open question). The second is at best a remote possibility—inflation is not an emergent issue.

As we near the August 2 “Day of Reckoning,” when the US government exhausts the extraordinary measures it has been taking since hitting the $14.3 trillion debt ceiling, Washington’s myopic debate makes for a tragic farce. While politicians have been toying with the possibility of voluntary default, outside the beltway real problems abound: unemployment, housing foreclosures, torched 401k plans that have stalled earned retirements, and college graduates struggling to begin their careers with paying jobs. Rather than pointing to the US government’s debt as the cause of slow growth, Gross should consider these headwinds.

But there is a more profound problem with this farce. continue reading…

Comments

levyadmin | March 29, 2011

Charts in last week’s entry, which contained approximations of real interest rates for various European countries, were unfortunately incorrect. The problem resulted from a silly mathematical error in the formula used to calculate the figures shown in the graphs. Accordingly, the author has recently uploaded a new version of the post, including corrected diagrams. He apologizes for the errors and any confusion they may have caused.

Comments

Daniel Akst | June 18, 2010

Levy public policy scholar Daniel Akst argues in this op-ed that the rise of unpaid internships is exacerbating income inequality. These internships are perceived to offer important professional experience and contacts. Yet young people without money can’t afford to take them, which means kids without money are at a further disadvantage in applying later for desirable paid work.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis