Keynes on low interest rates

Whatever the outcome of efforts to resolve severe economic difficulties in Europe and elsewhere, it is becoming increasingly clear that the next big economic crisis may not hinge on interest rates at all. One reason is that the world’s central banks, many of them following something like a Robinsonian “cheap money policy,” have managed to keep interest rates reasonably low in many countries. For example, it seems clear that yields on Spanish and Italian bonds are under control for now, after statements last month by Mario Draghi, the president of the ECB, that he was “ready to do whatever it takes,” to keep interest rates down. As made clear in this interesting and enlightening 2003 book edited by Bell and Nell (Stephanie Bell Kelton and Edward Nell), the theoretical argument for the Eurozone was badly flawed from the beginning. (Indeed, many in the world of heterodox economics saw these flaws from the beginning.) But, returning in this post to a key theme in Joan Robinson’s writings on the interest rate, I will offer some of the thoughts of John Maynard Keynes himself, who wrote in 1945 that:

The monetary authorities can have any rate of interest they like.… They can make both the short and long-term [rate] whatever they like, or rather whatever they feel to be right. … Historically the authorities have always determined the rate at their own sweet will and have been influenced almost entirely by balance of trade reasons [Collected Writings*, xxvii, 390–92, quoted from L.–P. Rochon, Credit, Money and Production, page 163 (publisher book link)].

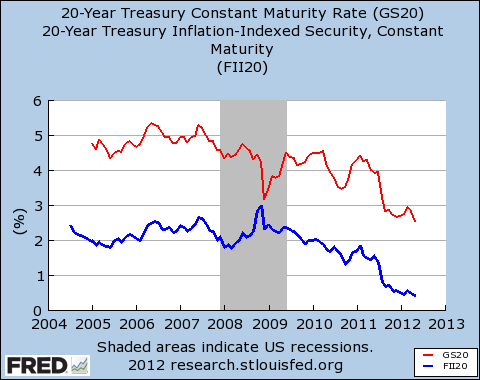

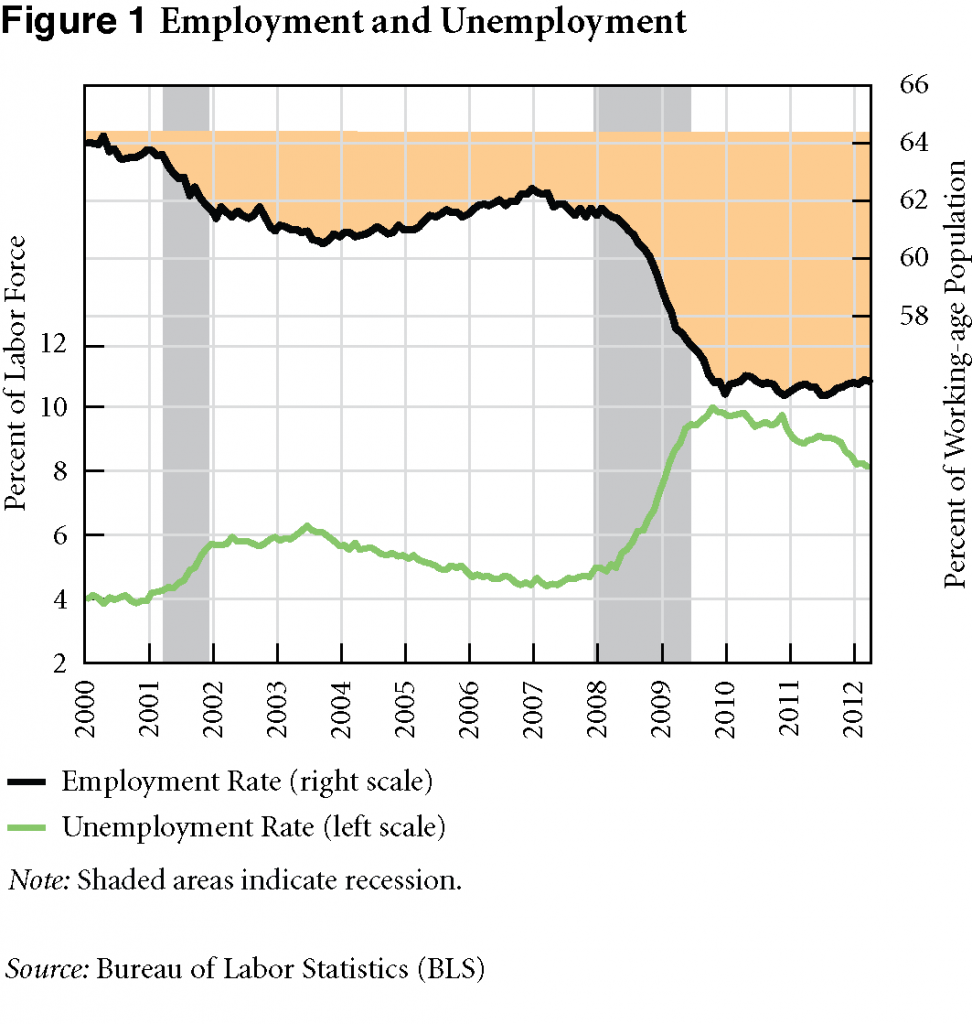

Here in the United States, the Fed has shown its ability as a liquidity provider to keep interest rates on relatively safe investments very low across the maturity spectrum, despite spending much more than it received in tax payments in calendar years 2009–2011, and presumably the current year. Keynes’s statement, much like the quote from Robinson mentioned above and the one in this earlier post, foretells this outcome.

Hence, recent US experience supports the view that calls for cuts in government spending and/or tax increases cannot be justified by fears that high deficits cause high interest rates at the national or global level.

* Note: The complete set of Keynes’s works is out of print in hardback and will be reissued as a 30-volume set of paperbacks later this fall, according the Cambridge University Press website. – G.H., September 3

ShareThis

ShareThis