An update on the Fed and the debt-limit impasse

A deal was reached over the weekend by congressional leaders and the President to resolve the debt-ceiling impasse. By that point, it was clear that the possible way out described by John Carney in a blog post to which we linked on Thursday would not be feasible. Nonetheless, the Fed’s ability to supply cash as needed if the deadline were missed had been made clear in official statements reported by the New York Times in Sunday’s early print edition. To wit, in response to concerns expressed by top banking executives,

“Mr. Geithner made it clear that the Treasury and the Federal Reserve had taken precautions so that payments for food stamps, military wages, and other federal obligations would not bounce, according to people involved in the call.”

An article posted to the Times website Saturday had phrased this point somewhat differently:

“Mr. Geithner assured [JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon] that the Treasury and Federal Reserve had taken steps to keep the payment system functioning smoothly, according to individuals briefed on the call.”

The phrase “keep the payment system functioning smoothly” is a euphemism known by Fed observers to entail in practice the types of functions described in the above quote of the print edition.

Obviously however, this use of overdrafts could not be continued very long, owing to the will of the negotiators and probably the relevant laws. These laws are intended to keep the Federal Reserve largely independent from the federal government. Hence, while the Fed honors checks written by the Treasury Department and presented to it by banks, the use of this privilege is extremely limited in the U.S. system, compared to “overdraft systems” of the type I described in this earlier post.

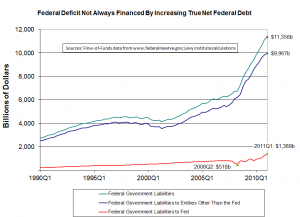

On the other hand, if the somewhat artificial distinction between the central bank and the central government were to be eliminated in the United States, the federal government would gain access to the printing press, enabling it hypothetically to back a virtually unlimited amount of outlays. Of course, this process would not create new “debt,” but rather new currency and bank reserves. Of course, the Fed itself can currently use its “printing press,” mostly to stabilize the banking system, a role that led to a massive expansion of bank reserves during the financial crisis of 2007–08.

In current mainstream macroeconomic thought, which is carrying the day in most of the developed world now, a system in which the government has control of the printing press is thought to court intolerable levels of inflation. However, in an economy growing as slowly as this one, it is extremely doubtful that excessive inflation would necessarily follow if the impasse were to be resolved by creating new currency and bank reserves, rather than by selling bonds, increasing taxes, or cutting spending. Yet given the legal independence of the Fed, the latter two options were the only ones open to the negotiators last weekend. Moreover, new taxes were unacceptable to many, if not most, in Congress. Hence, it now appears that the government may be about to make potentially devastating new cuts to key federal programs.

ShareThis

ShareThis