New Records for Fiscal and Regulatory Irresponsibility

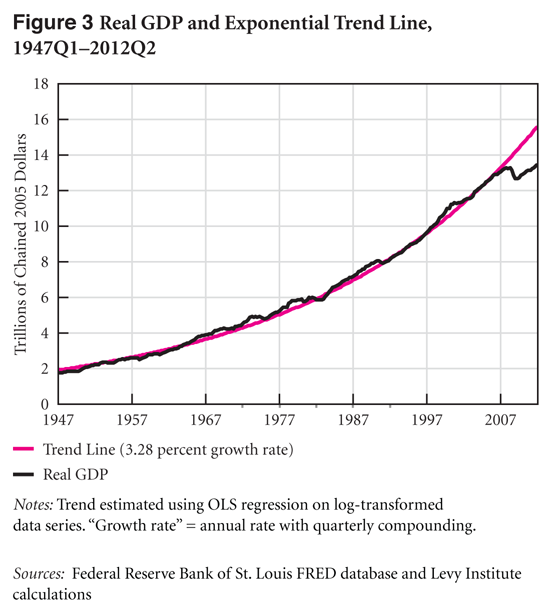

From 2009 to 2012, the US federal deficit shrank from 10.1% of GDP to 7% of GDP. That’s the fastest deficit reduction we’ve seen in six decades—and all before the fiscal cliff has kicked in. Here’s the chart from Jed Graham:

Put this alongside a record-setting contraction of government employment and a 7.9 percent unemployment rate, and what you have is a portrait of fiscal irresponsibility. A lot of this deficit reduction has to do with the fact that the economy is now growing (albeit feebly), instead of contracting, but looking at this chart should also reinforce how dangerous and unnecessary it is that we’ve decided to create an austerity crisis at this moment. (This “austerity crisis,” by the way, should really be understood to include both the possibility of going over, and staying over, the fiscal cliff AND the possibility of the cliff being replaced by a “grand bargain” on deficit reduction.) The last time the deficit was reduced at a faster rate was in 1937, when the government embraced a hard pivot to austerity and the economy tumbled back into recession.

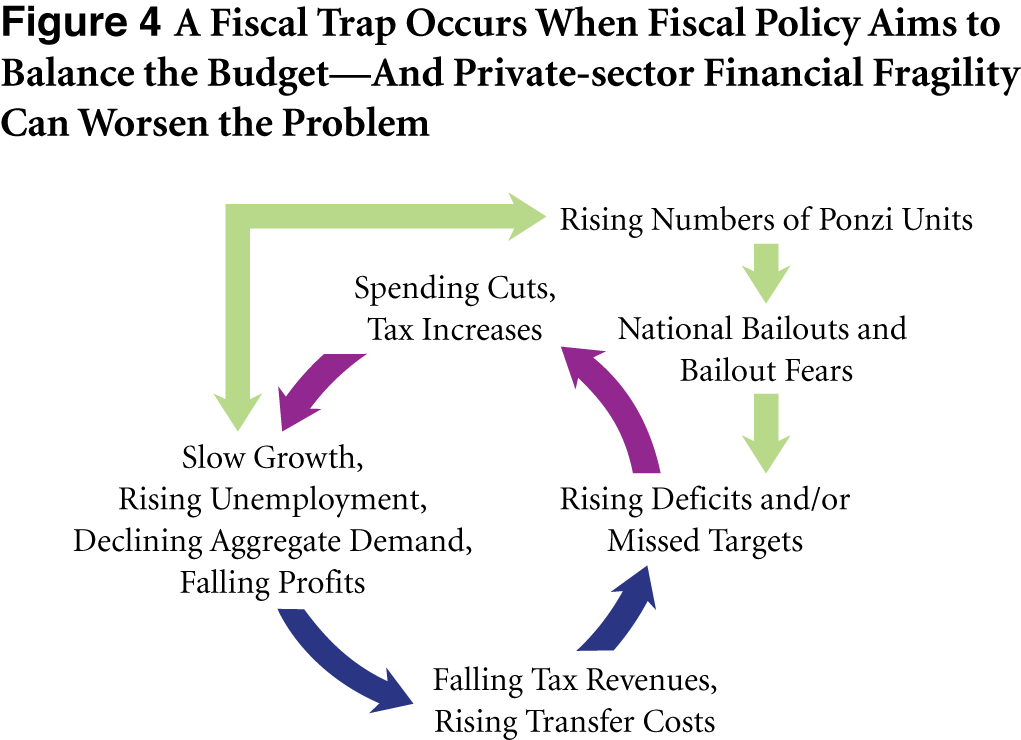

But don’t worry, we aren’t reliving the history of the 1930s. Not exactly. We are combining fiscal irresponsibility with regulatory negligence. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) reported on Sunday that the shadow banking sector, after contracting in 2008, has rebounded nicely and is doing just fine. Although it hasn’t quite seen the growth it did prior to the crisis, when it doubled in size from 2002 to 2007 (from $26 trillion to $62 trillion), the shadow banking sector reached $67 trillion globally in 2011—a new record, and “equivalent,” says the FSB, “to 111% of the aggregated GDP of all jurisdictions.”

ShareThis

ShareThis