Where Will US Growth Come From If Austerity Reigns?

That’s one of the questions the Levy Institute’s latest Strategic Analysis asks as it examines the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for growth and employment in the context of tighter and tighter government budgets. At the federal level alone we’re facing a well-publicized “fiscal cliff” in 2013, featuring large scheduled spending cuts and the expiration of a number of tax cuts.

As Dimitri Papadimitriou, Gennaro Zezza, and Greg Hannsgen note, the CBO “expects real GDP to grow by 2.2 percent in 2012 and by only 1 percent in 2013, and to accelerate once most of the fiscal adjustment has taken place, with growth reaching 3.6 percent in 2014 and 4.9 percent in 2015. The unemployment rate is expected to rise to 9.1 percent with the slowdown in economic activity, and to fall rapidly from 2014 onward, once the economy recovers.” This is all expected to take place in the presence of shrinking government deficits (based on the CBO’s “current law” projections for the federal budget).

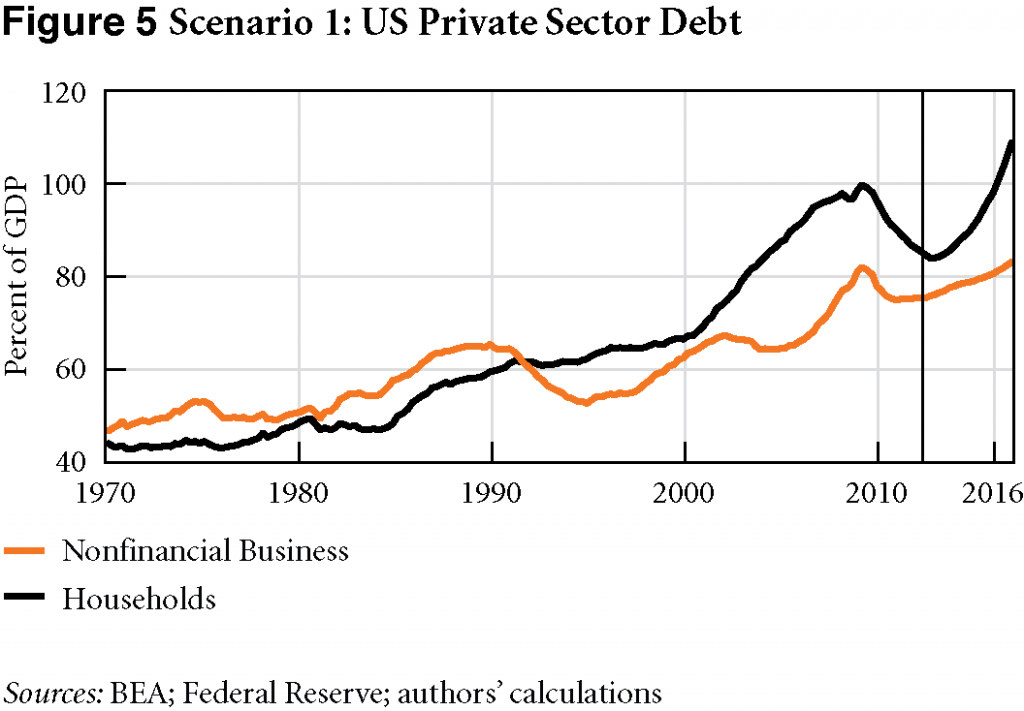

Using the CBO’s numbers, the Institute’s macro team ran a simulation to find out what would have to happen in the rest of the economy to make this combination of budget austerity and even tepid-to-moderate growth possible. The answer: dramatic increases in private sector borrowing. Here’s their graph showing, through 2016, the rise in private sector debt that would be necessary to attain the CBO’s economic growth projections in the context of austerity:

Since we cannot expect strong demand for US exports, given the state of the world economy, household and nonfinancial business debt would have to rise, relative to GDP, to levels that would return us to a situation “not so different from the one we had before the 2007-09 recession.” If you recall, that didn’t end well.

ShareThis

ShareThis