Michael Stephens | September 17, 2013

Back in 2009, Janet Yellen delivered a speech at the Levy Institute’s Minsky conference that explained how the financial crisis had changed her views about the role of central banks in handling financial instability. At the time she was the head of the San Francisco Fed.

The focus of her 2009 remarks was the question of how (or whether) central banks should try to counteract bubbles in asset markets. (Yellen also recalled the unfortunate topic of her 1996 conference speech: supposedly promising new innovations in the financial industry for better measurement and management of risk.) Bursting suspected bubbles has become the topic du jour in US monetary policy discussions, as it currently stands as the fashionable justification for tightening despite low inflation and high unemployment.

With the announcement that Larry Summers’ name has been withdrawn from consideration for the next Fed chair, the spotlight has turned to Yellen. Here (from the 2009 conference proceedings) is the text of her speech and a transcript of the brief Q&A that followed:

A Minsky Meltdown: Lessons for Central Bankers? (1)

It’s a great pleasure to speak to this distinguished group at a conference that’s named for Hyman Minsky. My last talk at the Levy Institute was 13 years ago, when I served on the Fed’s Board of Governors, and my topic then was “The New Science of Credit Risk Management at Financial Institutions.” I described innovations that I expected to improve the measurement and management of risk. My talk today is titled “A Minsky Meltdown: Lessons for Central Bankers?” and I won’t dwell on the irony of that. Suffice it to say that with the financial world in turmoil, Minsky’s work has become required reading. It is getting the recognition it richly deserves. The dramatic events of the past year and a half are a classic case of the kind of systemic breakdown that he—and relatively few others—envisioned.

Central to Minsky’s view of how financial meltdowns occur, of course, are “asset price bubbles.” This evening I will revisit the ongoing debate over whether central banks should act to counter such bubbles, and discuss “lessons learned.” This issue seems especially compelling now that it’s evident that episodes of exuberance, like the ones that led to our bond and house price bubbles, can be time bombs that cause catastrophic damage to the economy when they explode. Indeed, in view of the financial mess we’re living through, I found it fascinating to read Minsky again and reexamine my own views about central bank responses to speculative financial booms. My thoughts on this have changed somewhat, as I will explain.(2) continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | September 16, 2013

(The following was written by Sunanda Sen and first appeared at TripleCrisis)

A panic of unprecedented order has struck the crisis-ridden Indian economy. It brings to the fore the question of what led to this massive downturn, especially when the country was touted, not long back, as one of the high-growth emerging economies of Asia.

A volte-face, from scenes of apparent stability marked by high GDP growth and a booming financial sector to a state of flux in the economy, can completely change the expectations of those who operate in the market, facing situations with an uncertain future. Such possible transformations were identified by Kindleberger in 1978 as a passage from manias, which generate positive expectations, to panics, which head toward a crisis. While manias help continue a boom in asset markets, they are sustained by using finance to hedge and even speculate in the asset market, as Minsky pointed out in 1986. However, asset-market bubbles generated in the process eventually turn out to be on shaky ground, especially when the financial deals rely on short-run speculation rather than on the prospects of long-term investments in real terms. With asset-price bubbles continuing for some time under the influence of what Shiller described in 2009 as irrational exuberance, and also with access to liquidity in liberalised credit markets, unrealistic expectations of the future, under uncertainty, sow the seeds for an unstable order. The above leads to Ponzi deals, argues Minsky, with the rising liabilities on outstanding debt no longer met, even with new borrowing, since borrowers are nearing insolvency. Such situations trigger panics for private agents in the market, who fear a possible crisis situation. These are orchestrated with herd instincts or animal spirits in the market, as held by Keynes in 1936. In the absence of actions to counter the market forces, a possible crisis finally pulls down what in hindsight looks like a house of cards!

Indeed, when markets have the freedom to choose the path of reckless short-run financial investments, with high risks and high returns, the individual’s profit calculus eventually proves wrong in the aggregate, leading to a path of downturn; not just for the financial market, but for the economy as a whole. This is how manias lead to panics and then to crisis in an economy.

Characterisations like the above help to explain the slippages in the Indian economy. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | September 13, 2013

From a panel discussion yesterday at the George Washington University Law School on what we have(n’t) learned since the 2008 financial collapse (via Matias Vernengo). Galbraith begins by cautioning that these “lessons learned” frameworks often leave unchallenged the premise that the crisis is over and done with, when, as he argues, the events of 2008 were merely an “acute phase” of a broader crisis we are still living through.

[iframe src=”http://www.youtube.com/embed/rY-U9A7f-7o?start=822″ frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen width=”432″ height=”243″]

Comments

L. Randall Wray | September 11, 2013

I hope that all of you saw the very nice feature on Wynne Godley in the NYTimes. It is about time he’s getting the notice he deserved. I just came across a juicy quote from Wynne: “I want to say of neoclassical macroeconomics what I have sometimes said of certain kinds of fiction; I know that the world is not like that and I have no need to imagine that it is.”

Here’s an interview I recently gave to a Brazilian reporter.

Q: The crisis, which began with the collapse of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, will complete five years. What has changed in the world economy during this period?

LRW: Unfortunately, the global financial system was restored to its 2006 status through massive bail-outs by the public sector. It was not reformed. It was not investigated and prosecuted for fraud. Essentially, it was allowed to go back to doing what it did in the years preceding the crisis. Our real economies are still “financialized” with too much debt and with the financial sector taking far too big a share of profits. As a result, in most developed economies around the world, the real sector is very weak.

Of course, the success story was the BRICs—which largely avoided the worst of the crisis and even made gains in their real sectors. China’s development of its economy is unprecedented.

Q: The crisis is over? Is near the end? Still going to get worse?

LRW: No it is not over—especially in Euroland. While it might appear that the USA, UK, and some other developed non-European countries have recovered, as I said their real sectors are weak and their financial institutions have resumed risky practices. The global economic system is fragile and a full-blown crisis could return.

Q: U.S., Europe and emerging countries, such as Brazil, faced the crisis in different ways. How to describe these differences and which country or region got more successful in dealing with the crisis? continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | September 6, 2013

Robert Barbera, a regular contributor to the Levy Institute’s Minsky conferences, has a great post at Johns Hopkins’ Center for Financial Economics on the cycle of amnesia and remembrance that seems to plague mainstream economic theorists. Here’s a key passage:

Perhaps the most indictable offense that mainstream economists committed, from 1988 through 2008, was to retrace, step by step, Keynes’s path of discovery from 1924 through 1936. Wholesale deregulation of finance and categorical confidence in a reductionist role for central banks came into being as the conventional wisdom embraced the 1924 view that free markets and stable prices alone gave us the best chance for economic stability. To add insult to injury, the conventional wisdom before the crisis was embedded in models called “new Keynesian” which were gutted of the insights of Keynes. This conventional wisdom gave license to a succession of asset market boom/bust cycles that defied the inflation/deflation model but were, nonetheless, ignored by central bankers and regulators alike. Quite predictably, in the aftermath of the grand asset market boom/bust cycle of 2008-2009, we are jettisoning Keynes, circa 1924, for the Keynes of 1936.

It’s worth reading the whole thing: “Exit Keynes, the Friedmanite, Enter Minsky’s Keynes.”

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 15, 2013

In a new policy note, Jan Kregel draws out some of the policy lessons of the Cypriot deposit tax episode for plans to create a system of EU-wide deposit insurance. In addition to the necessity of a strong central bank (the ECB in this case) standing behind the deposit insurance scheme (which does not appear to be part of the current plans), Jan Kregel explains why a certain amount of moral hazard is inescapable.

We can see this by looking at two types of deposits that correspond to the dual functions of banks: deposits of currency and coin, and deposits created when loans are made. If a bank makes bad loans — and as Kregel points out, “it is the failure of the holder of the second type of deposit [loan-created deposits] to redeem its liability that is the major cause of bank failure” — the first type of depositor (of currency and coin) should not bear the brunt of these bad decisions. The role of deposit insurance, one might argue, is to provide such protection.

But since deposit insurance has to be extended to all of a banks’ deposits (up to a certain level), including those created by loans, moral hazard is inevitable. Ideally, deposit insurance would be structured in such a way as to distinguish between deposits based on currency and coin and deposits generated through loans, as well as between deposits created by good and bad loans (loans that default). But if you examine how the banking system functions, says Kregel, this isn’t operationally possible:

Unfortunately, it is impossible in practice to make these distinctions between reserve deposits, defaulted-loan-created deposits, and deposits created by loans that are current. It is for this reason that there are limits on the size of insured deposits based on the presumption that the first type of deposits will be relatively small household deposits created by the transfer of reserves and used as means of payment or store of value. It thus limits coverage of the other types of deposits. However, this is clearly inequitable for the deposits held by borrowers who are still current on their loans.

As he explains, with some help from Minsky, it is the means of payment function that makes these distinctions practically impossible (for more on why this is, read the note here). Kregel concludes that “It would thus seem impossible to design a truly fair deposit insurance scheme that eliminates the inherent moral hazard and the necessity of a contingent guarantee of the central bank.”

Comments

Greg Hannsgen | April 4, 2013

There have been many concerns expressed on the internet about the eventual necessity of reversing the Fed’s cheap-money policies, which include “quantitative easing,” as well as a near-zero federal funds rate.

One idea some have is that there are “too many bonds” in the Fed’s portfolio, and that problems will occur with insufficient demand whenever the Fed attempts to reduce its holdings. This doomsday scenario often seems to vex public discussion but is unlikely to materialize, given that the Fed can always make use of its ability to “make a market” for Treasury securities.

An alternative way of looking at the same situation is that there is a huge amount of money and money-equivalents on bank balance sheets and in nonfinancial corporate coffers, and that the tendency of the modern economy toward financial fragility will eventually lead to risky loans and investments using these funds. (Jeremy Siegel adopts this view in the FT, with, however, an unfortunate emphasis on the possibility of a takeoff of inflation. Inflation remains below the Fed’s 2-percent approximate objective, and the greater risk by far is still recession. An Alphaville comment on his column makes the point that the threat of fragility remains regardless of whether banks have excess reserves on hand.) Concerns have already emerged about “junk” bonds, so-called leveraged loans, and other effervescent areas of finance. Of course, the problem then becomes for the authorities to implement an appropriate restraint on financial excesses. One conventional method would be to increase interest rates using open-market operations, which would of course probably entail the sale of securities. This scenario unfortunately might lead to some serious threats to financial stability, including problems that short-term and/or variable-rate borrowers might have meeting payment commitments on their debts, if the Fed were to raise interest rates sharply.

One big historical example of this kind of fragility is the rise in short-term interest rates that occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s at the behest of the Fed. The resulting delta-R effect helped to bankrupt Mexico, among other disastrous impacts. Many years before that, the Fed was more inclined to use direct controls on credit, restricting the amount of money banks could lend out.

Key to the situation today, efforts are ongoing in Washington to formulate and implement appropriate rules to insure that various kinds of bank lending do not get out of hand in the first place. Efforts of this type would be unlikely to completely prevent future crises, but, if effective, would act to reduce fragility. Among other benefits, this approach might also permit the recovery in housing investment—currently only in a fledgling phase—to continue. Given the problems that sharp interest-rate increases can bring, it would also be helpful to keep the effects of moderate inflation in perspective, and to cope with inflation in non-destabilizing ways.

Comments

Michael Stephens | March 19, 2013

Yesterday, Dimitri Papadimitriou joined Ian Masters to discuss the response to the banking crisis in Cyprus. The plan on the table, in which Cypriot banks would impose a deposit tax (9.9 percent on deposits above €100,000, and 6.75 on deposits below that) in order to gain access to a €10 billion bailout from the troika, unconscionably makes small depositors pay for someone else’s regulatory blunders — and is likely to be ineffective anyway, said Papadimitriou.

The entire episode once again points to the fundamentally unworkable setup of the eurozone, in which each member-nation is (ostensibly) responsible for its own banking system. For more on these deeper structural problems, see this policy note: “Euroland’s Original Sin.”

Listen to the interview here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | February 25, 2013

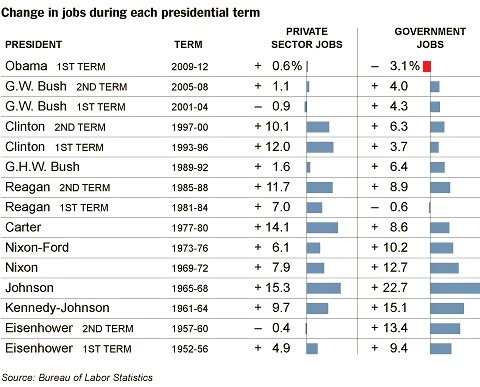

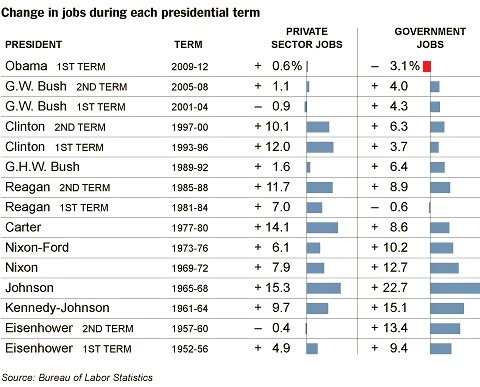

Randall Wray joined Suzi Weissman on her “Beneath the Surface” radio show on Friday. They began the interview with a discussion of the policy blunders that are creating headwinds for the US economy, including the expiration of the payroll tax cut, the decline of real per capita government spending, and, as Wray put it, “the government sucking jobs right out of the economy.” He’s not referring here to the walking corpse of the theory that regulatory uncertainty is to blame for the slow recovery, but to the fact that government is holding back job growth far more directly: by laying off workers at an unprecedented rate. For context, look at this chart put together by Floyd Norris (highlighted):

They also addressed this Marketplace segment on the “death of inflation,” ongoing threats from the financial system, and some ideas for financial reform that are currently being tossed around. On the latter, Wray argued that the idea of a financial transactions tax (being considered by a number of EU countries) is a second-best or partial solution. Instead of sin taxes and other such “economists’ solutions,” as he described them, Wray recommended coming at the problem more directly: by outlawing certain speculative activities and going after practices like high-frequency trading. They closed with a discussion of the prospects of another financial crisis emerging.

Listen to the interview here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | February 24, 2013

Tomorrow at UCLA, Randall Wray, Frank Partnoy, and Robert Brenner will discuss “The Economic Crisis: Causes, Consequences, and What’s Next” as part of the annual colloquium series of the Center for Social Theory and Comparative History.

The speakers will consider the origins and results of the ongoing global economic crisis. They will give special attention to the rise of finance and the role of financial markets and institutions in its onset, spread, and ultimate consequences. How has the meltdown of Wall Street, its bailout by government, and its apparent recovery affected the macroeconomy and the future of finance itself? Are the great banks and other leading financial institutions now more or less likely to experience new meltdowns in the foreseeable future? Will the real economy see a new surge of growth, continuing stagnation, or renewed crisis? These are only some of the issues that will be addressed at this colloquium.

Monday, 25 February 2013

2:00-5:00 pm

History Conference Room, 6275 Bunche

See the flyer for more information:

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis