This posting is by Levy senior scholar Philip Arestis, University of Cambridge and University of the Basque Country, and Theodore Pelagidis, European Institute, London School of Economics and University of Piraeus.

A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of austerity. All the powers of old Europe have entered into an unholy alliance to exercise this spectre, about which all of us should be depressed. Europe probably will be soon enough.

Why this sudden emphasis on austerity, when the well-known lessons of history are that in times of recession fiscal stimulus is the best medicine? Some European countries are chronic over-spenders of course, but others with strong balance sheets have announced austerity programs as well. Why? The short answer is that it is all about the banks.

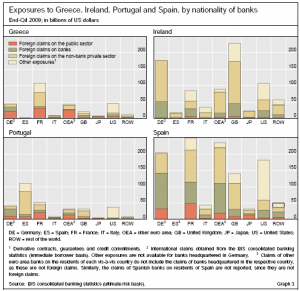

Europe’s financial institutions are loaded with potentially toxic sovereign debt issued by Greece and other shaky countries around the European periphery. French banks are said to be loaded with 75 billion euros of toxic Greek bonds; one can now understand President Sarkozy’s furious campaign to rescue Greece. Taken together, Spain, Greece and Portugal are believed to have planted a 2.2 trillion euro time bomb on the balance sheets of European banks.

The value of these assets has already plunged, threatening bank solvency, choking off lending and leaving the taxpayers of such solvent nations as Germany with Hobson’s choice: foot the bill for the prodigality of Greece and other euro area nations in similar positions, or bear the expense of bailing out their own banks. Doing neither, for now at least, appears to be unthinkable.

Thus the continent-wide turn toward austerity. If state budgets are restricted, so the magical thinking goes, wonderful things will happen. Sovereign bond prices will rise, rescuing imperilled banks. Moribund interbank lending will be resuscitated. Government borrowing costs will decline. Economies will be reinvigorated. The embrace of austerity is also easier to understand in a political context. It is clear that European politicians are incapable of directing stimulus to productive ends, and the public continues to reject tax increases to cover the future deficits that today’s stimulus would create.

The problem is that embarking on austerity now will only make a bad situation worse. In fact austerity increases the risk of a great many dreaded outcomes in Europe, including negative GDP growth, sovereign default, political instability and shuttered capital markets. These things make bank failures more likely, not less. It is actually the lack of a more powerful and more systematic stimulus that raises the risks of a double-dip recession. In Europe in particular, the near absence of a stimulus has brought the euro area very close to dissolution. It is the deep and prolonged recession that finally revealed member-states’ huge public debts, and made borrowing so expensive for most of the member-states and unbearable for others (Greece). Banks suffer by keeping trillions in devalued sovereign bonds hidden on their balance sheets; and nobody really knows which and how many banks are in this tragic situation. Would draconian cuts in the context of Europe’s fragile growth rate solve the problem? Surely not.

What is needed right now is spending, not saving, particularly in Germany. It is noteworthy that in the U.S., this kind of Keynesianism—mixing consuming and investment budgetary expenses with some tax credits—saved the system from collapse in 2009 and retained, to a great extent, a certain satisfactory level of economic activity.

The ‘over-borrowing’ of Greece and other European countries in a similar position should not be attributed to naïve Keynesianism. The real problem is that these countries, by joining the Euro, have deprived themselves of an appropriate domestic monetary policy. An extremely hard euro policy combined with cheap credit quickly eroded domestic competitiveness while raising demand for imports, which had become cheaper. The result was a ballooning current account deficit that reached 14% of GDP in Greece (2008), a deficit that requires corresponding capital inflows. Given declining domestic competitiveness, these flows could not be foreign direct investment. Thus, the government had to take over and sell bonds to finance a fast-deteriorating current account.

So if austerity is not the answer, what should be done to help the weakest Mediterranean countries stabilize their economies and thereby avoid a painful dissolution of the European Monetary Union? Aside from the perennial problem of Greece, where governments always lie about deficits and citizens always lie about their income, we should not forget the responsibilities of the EMU itself. It should have acted differently long ago, but it is not too late for it to change course in time to avert disaster. There are three important steps to be taken, all of them at odds with what the G20 decided in the first week of June.

First and foremost, the European Central Bank should buy as many toxic sovereign bonds as necessary to stabilize the market. Second, ECB should lower interest rates close to zero, as has been done in the United States. Last but not least, countries with huge surpluses, such as Germany, should be convinced to spend more and tax less, which means smaller current-account deficits for the weaker EMU partners and possibly a little more inflation for Germany. It is completely absurd for any surplus country within a monetary union to implement austerity measures while maintaining a current account surplus.

In sum, if contractionary policy prevails globally and especially around Europe, Greece and similar countries might find it even harder to drive their economies through an export-led recovery. It would then be easy to predict what will happen to those banks keeping toxic skeletons in their closets.

ShareThis

ShareThis