Michael Stephens | November 11, 2011

1) Marshall Auerback, at New Economic Perspectives, digs into the issue of whether the ECB is legally permitted to engage in the sort of “lender of last resort” activities that many think are key to mitigating this crisis:

The notion that it cannot act as lender of last resort is disingenuous: The ECB does have the legal mandate under its “financial stability” mandate which was provided under the Treaty of Maastricht. True it is fair to say that the whole Treaty of Maastricht is full of ambiguity. The institutional policy framework within which the euro has been introduced and operates (Article 11 of Protocol on the Statute of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) and of the European Central Bank) has several key elements. One notable feature of the operation of the ESCB is the apparent absence of the lender of last resort facility, which is an issue raised by the WSJ today, and which Draghi uses to justify his inaction. But it’s not as clear-cut as suggested: The Protocols under which the ECB is established enables, but does not require, the ECB to act as a lender of last resort.

Proof that the ECB exploits these ambiguities when it suits them is evident in its bond buying program. The ECB articles say it cannot buy government bonds in the primary market. And this rule was once used as an excuse not to backstop national government bonds at all. But this changed in early 2010, when it began to buy them in the secondary market. The ECB also has a mandate to maintain financial stability. It is buying government bonds in the secondary market under the financial stability mandate. And it could continue to do so, or so one might argue that it could. True there is now great disagreement about this within the ECB. It has been turned over to the legal department, which itself is in disagreement, which ultimately suggests that this is a political judgement, and politics is what is driving Italy (and soon France) toward the brink.

Read the rest here.

2) Brad Plumer of the Washington Post runs down the reasons (with rejoinders from Paul De Grauwe) why the ECB might be unwilling to step in as lender of last resort (hint: the words “inflation” and “moral hazard” come up a lot).

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 10, 2011

Here is another flattering mention of Wynne Godley‘s prescient writings on the euro, this time from John Cassidy’s blog at the New Yorker. (Cassidy sat in on the Keynes side of this week’s “Keynes vs. Hayek” debate.)

Many of Godley’s publications at the Levy Institute (“haven for heterodox thought,” as Cassidy calls it), including his early observations about the exponential growth in private debt that marked the Greenspan economy, can be found here.

Gennaro Zezza, together with Marc Lavoie, is also putting together a new book featuring Wynne Godley’s writings (The Stock-Flow Consistent Approach: Selected Writings of Wynne Godley). It will be released in early 2012:

This book is the intellectual legacy of Wynne Godley, the famous British economist who was the head of the Department of Applied Economics at the University of Cambridge for nearly 20 years, after having been deputy director of the Economic section at the UK Treasury. These selected writings are useful not only as a summary of the evolution of Godley’s analysis, but also equip economists with new tools for the achievement of sustainable economic growth. Professor Godley’s work always originated from puzzles in the real world economy, rather than from curiosities in economic models, and his work has retained its practicality; the stock-flow models have proved to be effective in predicting recent recessions. These essays present Godley’s challenge to accepted wisdom in the field of macroeconomic modelling, which, in his opinion, did not reflect the economics that he had learned by working on practical matters for the Treasury in the 1960s. Godley developed post-Keynesian traditions and created models which fully integrate theory with the financial system and real demand and output.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 8, 2011

Among the (many) obstacles to working out a solution to the crisis in the eurozone is resistance to schemes that involve debt buyouts, national guarantees, mutual insurance, and fiscal transfers. Stuart Holland has a new one-pager and policy note in which he suggests a twin-track strategy for solving the crisis that does not rely on any of the above.

His recommended strategies revolve around using the EIF (European Investment Fund) as an issuer of eurobonds, and having member-states with at-risk bonds convert a share of them, through enhanced cooperation, into EU bonds (allowing, for instance, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, and Finland to keep their own bonds). According to Holland, neither of these strategies would require ratification by national parliaments or an alteration of the EU treaty. The one-pager builds on an earlier policy note by Holland and Yanis Varoufakis, “A Modest Proposal for Overcoming the Euro Crisis.”

Read Holland’s one-pager here and the elaborated policy note version here.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

At Pragmatic Capitalist, Cullen Roche writes about the “eerily prescient” predictions regarding the euro made by Modern Money Theorists and economists looking at sectoral balances. Roche quotes from Randall Wray’s Understanding Modern Money (see in particular p. 91ff), a paper by Stephanie Kelton (Bell), and a Wynne Godley article written in 1997 (“Curried Emu — the meal that fails to nourish,” Observer, Aug. 31). From Godley:

If a government does not have its own central bank on which it can draw cheques freely, its expenditures can be financed only by borrowing in the open market in competition with businesses, and this may prove excessively expensive or even impossible, particularly under ‘conditions of extreme emergency.’ … The danger, then, is that the budgetary restraint to which governments are individually committed will impart a disinflationary bias that locks Europe as a whole into a depression it is powerless to lift.

See also Godley’s earlier piece (1992) in the London Review of Books, “Maastricht and All That“:

I recite all this to suggest, not that sovereignty should not be given up in the noble cause of European integration, but that if all these functions are renounced by individual governments they simply have to be taken on by some other authority. The incredible lacuna in the Maastricht programme is that, while it contains a blueprint for the establishment and modus operandi of an independent central bank, there is no blueprint whatever of the analogue, in Community terms, of a central government. Yet there would simply have to be a system of institutions which fulfils all those functions at a Community level which are at present exercised by the central governments of individual member countries.

With regard to Godley’s prescience, take a look at this policy note from 2000 on the US economy (“Drowning in Debt“) that discusses the eye-popping rise in private indebtedness (“…it is certainly entirely different from anything that has ever happened before–at least in the United States”). It’s really worth reading the whole thing (only five pages).

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 3, 2011

[The following is the text of Senior Scholar Randall Wray’s presentation, delivered October 28, 2011, at the annual conference of the Research Network Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies (IMK) in Berlin. This year’s conference was titled “From crisis to growth? The challenge of imbalances, debt, and limited resources.”]

It is commonplace to link Neoclassical economics to 18th or 19th century physics with its notion of equilibrium, of a pendulum once disturbed eventually coming to rest. Likewise, an economy subjected to an exogenous shock seeks equilibrium through the stabilizing market forces unleashed by the invisible hand. The metaphor can be applied to virtually every sphere of economics: from micro markets for fish that are traded spot, to macro markets for something called labor, and on to complex financial markets in synthetic CDOs. Guided by invisible hands, supplies balance demands and all markets clear.

Armed with metaphors from physics, the economist has no problem at all extending the analysis across international borders to traded commodities, to what are euphemistically called capital flows, and on to currencies, themselves. Certainly there is a price, somewhere, someplace, somehow, that will balance supply and demand—for the stuff we can drop on our feet to break a toe, and on to the mental and physical efforts of our brethren, and finally to notional derivatives that occupy neither time nor space. It all must balance, and if it does not, invisible but powerful forces will accomplish the inevitable.

The orthodox economist is sure that if we just get the government out of the way, the market will do the dirty work. Balance. The market will restore it and all will be right with the world. The heterodox economist? Well, she is less sure. The market might not work. It needs a bit of coaxing. Imbalances can persist. Market forces can be rather impotent. The visible hand of government can hasten the move to balance. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 2, 2011

In the LA Times today, Dimitri Papadimitriou writes about the very real danger of seeing the end of economic union in Europe; a union Papadimitriou insists is ultimately worth saving.

He quickly sketches out what a serious first step toward a solution might look like (rather than this patchwork of half-measures that is sure to be torn apart). The latest set of deals don’t look like they will provide the “breathing room” they’re intended to create. What’s needed, Papadimitriou suggests, is for the European Central Bank to step forward with a bond-buying program; something that would perform a function similar to that of the US TARP program.

But calming volatility, providing real breathing room, is just the first step. The next steps in the eurozone triage ultimately need to include serious efforts to tackle the underlying growth problem in Greece:

Greece lacks both an industrial base and the widespread availability of technology. It simply can’t be productive enough to compete with neighbors such as Germany, France or the Netherlands. It’s in deep recession and doesn’t have the resources to grow out of it, even with an easing of its still-enormous debt level.

Most of the austerity measures and reforms in place — and calls to continue or increase them — won’t work. Raising taxes in a society distinguished by flagrant tax evasion has only boosted the shadow economy …

Read the entire op-ed here.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

C. J. Polychroniou delivers his verdict on the recent eurozone “haircut” deal for Greece (that already looks likely to fall apart given yesterday’s news that Papandreou will submit the plan to a sure-to-be-defeated referendum). In this new one-pager, he highlights a number of elements that make the deal destined for failure—even if the referendum were to succeed. The most glaring flaw, says Polychroniou, is the absence of any credible plan for growth (and as the leaked “troika” document reveals, even some policymakers in the eurozone are coming to admit that “austerity!” does not constitute such a plan):

More fundamentally, a 50 percent haircut alone will not solve the Greek debt problem. When all is said and done, neither recapitalizing European banks nor turbo-charging the EFSF (especially with dubious schemes) can credibly resolve the eurozone crisis without also enacting policies to promote long-term growth. And at this stage, the only viable and immediate solution to reviving the economies of Greece and the other European member-states is through public spending and quantitative easing. But these are policies that are precluded by Germany’s incorrigibly stubborn disposition toward expansionary fiscal consolidation.

Read the one-pager here.

Comments

Gennaro Zezza | November 1, 2011

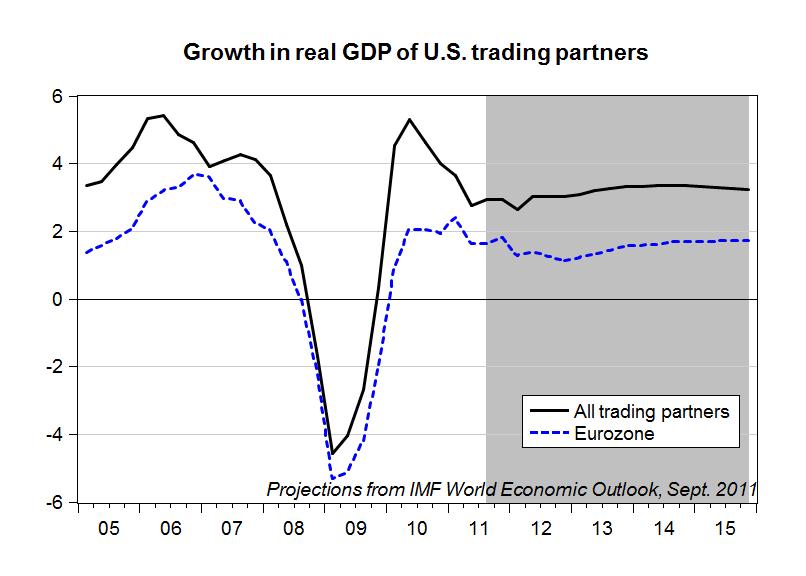

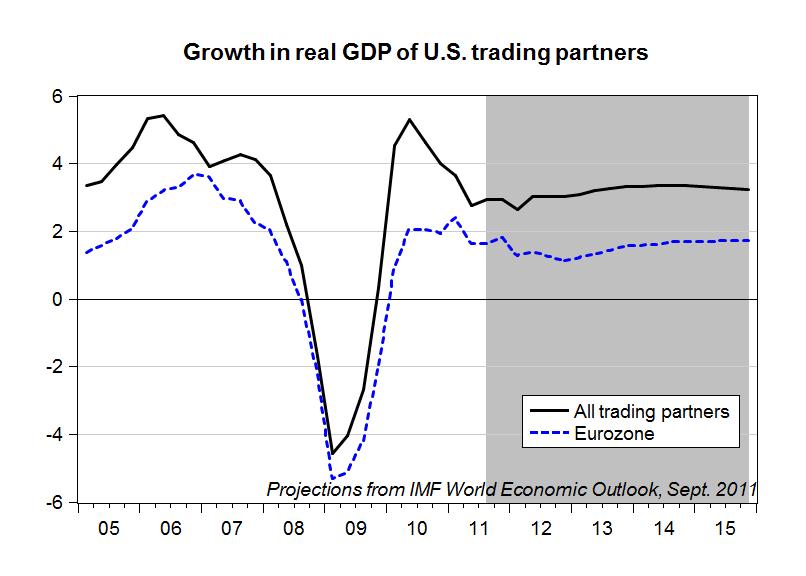

This post provides our latest update of the quarterly figures for the real and nominal GDP of U.S. trading partners (1970q1-2016q4), which were presented a few years ago in a Levy Institute working paper and have now been updated to the second quarter of 2011, with predictions up to 2016 based on the latest IMF World Economic Outlook.

The database has been requested over the years by other researchers, so we decided to put it up on our web site. It is, and will be, available here: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/gdp_ustp.xls

Our index for the annual growth rate in the real GDP of U.S. trading partners, reproduced above, now shows that no boost in U.S. exports from accelerating growth in the rest of the world can be expected. More specifically, according to the IMF the eurozone will not contribute much to global growth, and if fiscal consolidation in Southern European countries will indeed be implemented, we expect a further slowdown in the area. Given that the eurozone accounts for roughly 16 percent of U.S. exports, the impact on the U.S. economy of a European slowdown, through trade, will not be dramatic — certainly not as dramatic as the potential negative impact on financial wealth if the eurozone sovereign debt crisis spirals out of control.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 31, 2011

At Eurointelligence, Rob Parenteau digs into a recently-leaked “Troika” (the IMF, European Central Bank, and European Commission) document that discusses the outlines of a Greek debt restructuring deal. Among the revelations Parenteau extracts from the document is evidence of a growing willingness to concede that fiscal consolidation is not expansionary. As Parenteau comments:

In 2009 and 2010, citizens across the eurozone were sold large, multi-year tax hikes and government spending cuts on the idea that [expansionary fiscal consolidations] are commonplace and achievable, and besides, balanced fiscal budgets are a sign of prudence and moral purity. In fact, a closer inspection of history suggests fiscal consolidation will tend to be expansionary only under fairly special conditions, namely when accompanied by a) a fall in the exchange rate that improves the contribution of foreign trade to economic growth, and b) a fall in interest rate levels that improves interest rate sensitive spending by households and firms.

Notice that neither of these special conditions are automatic, and neither of them have been present in the eurozone of late.

Read the whole article, including a link to the leaked document, here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 25, 2011

Research Associates Marshall Auerback and Rob Parenteau have a long piece up at Naked Capitalism taking on the lazy anthropology that poses as economic analysis regarding Greece and the euro zone crisis. With respect to the image of Greeks lolling about living off an absurdly generous dole at the expense of frugal Germans, they provide some helpful contextual data:

… the Greek social safety nets might seem very generous by US standards but are truly modest compared to the rest of the Europe. On average, for 1998-2007 Greece spent only €3530.47 per capita on social protection benefits… By contrast, Germany and France spent more than double the Greek level, while the original Eurozone 12 level averaged €6251.78. Even Ireland, which has one of the most neoliberal economies in the euro area, spent more on social protection than the supposedly profligate Greeks.

One would think that if the Greek welfare system was as generous and inefficient as it is usually described, then administrative costs would be higher than that of more disciplined governments such as the German and French. But this is obviously not the case, as Professors Dimitri Papadimitriou, Randy Wray and Yeva Nersisyan illustrate. Even spending on pensions, which is the main target of the neoliberals, is lower than in other European countries.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis