How Long Until Greece Recovers?

The Levy Institute has completed its most recent medium-term projections for the Greek economy. The outlook, unsurprisingly, isn’t reassuring.

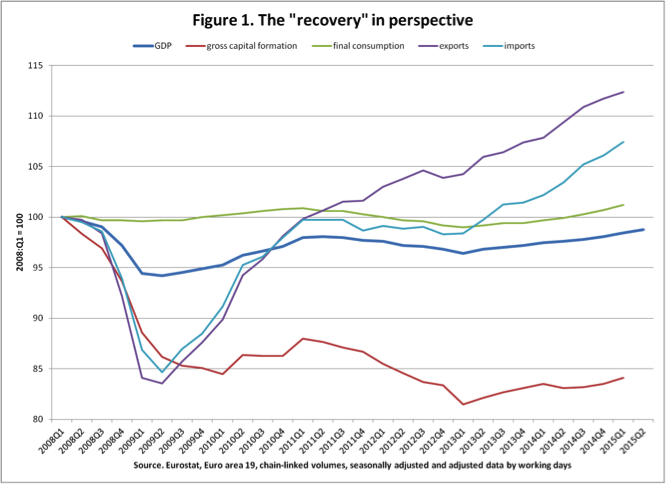

The baseline simulation, which assumes the continuation of current policy, shows the GDP growth rate turning positive in 2017 and reaching 2 percent in 2018. Yet, in a reflection of how much damage has been done by the crisis, even if Greece managed a growth rate around that pace (2.1 percent per year), it would take until 2030 for real GDP to return to its 2006 level. It’s fair to wonder whether such a delayed recovery — with little relief on the horizon for the elevated numbers of poor and unemployed in Greece — is politically and socially sustainable.

And there’s worse news in the report. The baseline generated by the authors’ model for Greece reflects a scenario in which future growth would be export-driven. But this increase in Greek exports would not be generated primarily by price competitiveness (“the price elasticity of Greek exports is low while the income elasticity is high”). That is, the decline of Greek wages — the centerpiece of the official “internal devaluation” strategy — isn’t projected to produce much of a payoff in terms of net exports.

Instead, the rise of exports in this scenario is almost entirely due to assumptions about the economic health of Greece’s trading partners; assumptions taken from the IMF. And as the authors caution, the IMF is likely overstating European growth prospects. So this lost decade-and-a-half for Greece (more, if you’re counting from the onset of the crisis) is actually the “optimistic” scenario.

What can be done? Some of the plans being considered are simply too tame. The authors run a second simulation based on the implementation of a “Juncker Plan”: an increase in public investment for Greece, funded by European institutions, of €1 billion in 2016, €2 billion in 2017, and €3 billion in 2018. The results suggest such a program could help raise GDP growth rates (to -0.4 percent in 2016, 2.9 percent in 2017, and 2.8 percent in 2018), but according to the authors the lag between output and jobs would still leave unemployment too high for too long. Something better targeted, and less reliant on the good will of European institutions, is required. More on that soon.

Read the full Strategic Analysis here and the One-Pager version here.

ShareThis

ShareThis