Michael Stephens | November 29, 2011

In a new one-pager C. J. Polychroniou illustrates how dire the situation in Euroland is becoming, running briefly through the outlooks for Greece, Portugal and Ireland, Italy and Spain, Belgium, France, and Germany. From his entry on Italy and Spain (emphasis mine):

Both nations are currently engulfed in debt flames (in spite of the fact that Spain does not have a public-finance crisis, as its debt-to GDP ratio is just slightly over 60 percent and lower than that of Germany and France, while Italy, at only 4.6 percent of GDP, runs one of the lowest budget deficits in the EU) and being administered the usual neoliberal medication (a sure way to worsen their condition!).

Read the rest here.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

In a recent interview Dimitri Papadimitriou talked about the EU leadership’s failure to prevent the euro crisis from entering its terminal phase and ran through the likely repercussions for the US financial system. Papadimitriou cites $3 trillion in exposure for US finance, half of which is mutual fund investments in European banks and sovereign debt—and he notes that this doesn’t even include the fallout from any unraveling of credit default swaps.

Unless the European Central Bank steps up as lender of last resort (an announcement that it is willing to engage in unlimited purchases of sovereign debt should be sufficient), we will see the end of the euro project, says Papadimitriou. He contrasts the Federal Reserve’s $29 trillion worth of pledges to save the banking system with the anemic actions of the ECB (less than half a trillion euros so far). This is, says Papadimitriou, a truly historic moment we are witnessing, as the European project falls apart before our eyes.

Listen to the interview with Ian Masters here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 28, 2011

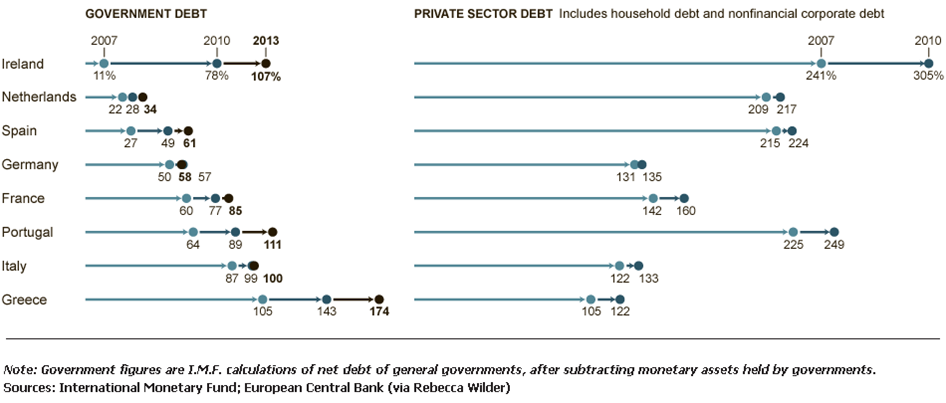

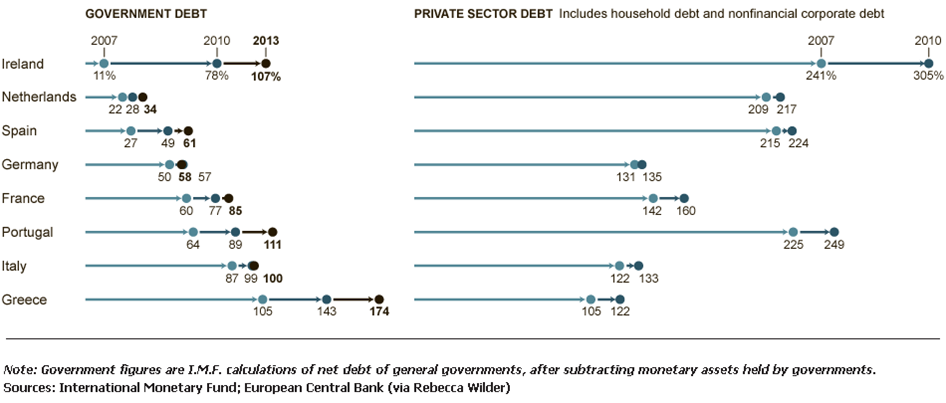

In a new one-pager, Dimitri Papadimitriou and Randall Wray team up to offer their take on the confusion that seems to afflict many approaches to the eurozone crisis. Government spending did not cause this crisis, they argue, and austerity will not solve it. Wray and Papadimitriou include this chart showing both government and private debt ratios for key EMU nations. They note that prior to the crisis only Italy and Greece were substantially beyond the 60 percent Maastricht limit for government debt. But if you look at private sector debt, every one of these countries had debt ratios above (well above, for most) 100 percent of GDP. (click to enlarge)

The problem, in other words, goes well beyond Mediterranean profligacy. “There was something else going on here;” they write, “something that has been in the works for the past 40 years: a general trend in the West of rising debt-to-GDP ratios. While government debt is part of this trend, it is dwarfed by the rise in private debt. Taking the West as a whole, government debt grew from 40 percent of GDP in 1980 to 90 percent today, while private debt grew from over 100 percent to roughly 230 percent of GDP.”

Moreover, tackling the crisis through austerity is bound to fail as long as policymakers continue to be oblivious to balance sheets. The only way that austerity in the periphery will not cripple economic growth (and therefore worsen the private debt problem) is if there is a substantial reduction in current account deficits in the periphery. But this is only possible if Germany reduces its current account surplus—and there is no evidence that key policymakers will make this happen. That leaves us, say Wray and Papadimitriou, with deflation as the only mechanism for restoring competitive balance. In other words, it leaves us with an approach that makes default, and the collapse of the EMU, more likely.

Read the one-pager here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 23, 2011

In a new policy note Marshall Auerback argues that discussions of how to solve the euro crisis often conflate two distinct issues: solvency and insufficient demand. “Policymakers want the ECB to do both,” he writes, “but in fact, the ECB is only required to deal with the solvency issue. When you do that in a credible way, then you get the capital markets reopened and you give countries a better chance to fund themselves again via the capital markets.”

Auerback considers a proposal that would, by addressing national solvency, give member-states the space necessary address the growth problem. The proposal (developed also by Warren Mosler) calls for the ECB to make annual distributions of euros to national governments on a per capita basis. By contrast with targeted bailouts, these per capita distributions would avoid problems of moral hazard, says Auerback. They would also provide the ECB with a more effective policy lever (withholding of payments) to ensure compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact. Concerns about inflation with respect to this plan are misplaced, he argues:

To anticipate the screams of the hyperinflation hyperventillistas, the revenue sharing proposal would be noninflationary. What is inflationary with regard to monetary and fiscal policy is actual spending. These distributions would not alter the actual annual government spending and taxation levels demanded by the austerity measures and SGP constraints. They would simply address the solvency issue, which has effectively cut the PIIGS off from market funding (because the markets believe they are insolvent).

Read the whole thing here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 18, 2011

(Update added below)

In our last post on this topic, we found the head of the Bundesbank citing legal obstacles (Article 123 of the EU treaty) as the reason why the European Central Bank cannot step up as lender of last resort. Can the ECB work around that Article 123 restriction?

In the last couple of days we’ve seen reports of a new, convoluted approach in which the ECB would lend to the IMF, which would in turn directly buy member-state debt. Marshall Auerback noted another possible workaround, via a mechanism the ECB has already used (though not to the extent that would be necessary): the ECB can get around the prohibition on buying member-country debt in the primary market by doing so through the secondary market. (On the ECB buying bonds in the secondary market, Brad Plumer of the Washington Post has a nice quote from Richard Portes of the London Business School: “If that’s illegal, then officials should already be in jail. Because they’ve been doing it sporadically since May of 2010.”)

At Modeled Behavior, Karl Smith questions whether this would really work. He points out that while the ECB has conducted limited buying of this sort in the secondary market, what would be required for the ECB to act as lender of last resort would be unlimited buying. Smith then runs down the legal obstacles to unlimited ECB operations, citing two provisions that could stand in the way of this secondary market solution:

The first provision says that the ECB cannot target a price for Italian Debt on the secondary market.

The second provision says that ECB cannot guarantee that newly issued Italian debt will stand as collateral under repurchase agreements.

If the ECB were able to do either of the above things then it could provide guaranteed liquidity to the holders of Italian debt and cause the yield to collapse towards the overnight rate.

Smith ends by offering a couple of alternative routes, but in many ways, this may all be beside the point. If you read between the lines in interviews given by people like Jens Weidmann, what comes through is not simply an expression of regret regarding the obstacles to a lender of last resort function, but something more like an endorsement of the value of these Article 123-type restrictions. The barriers, in other words, seem to be more a matter of ideology and politics.

Update: Ramanan adds some serious value to this discussion in comments (go take a look), including a link to a 2006 paper by Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie in which they consider this very issue of working around the rules prohibiting the ECB from directly financing member-state Treasuries. From the paper (emphasis mine): continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens |

It has become a cliché that the survival of the European Union (EU) depends on its ability to reform, either through enlargement—greater economic and fiscal coordination in the direction of some sort of federal state—or by getting smaller, with the eurozone becoming a true optimum currency area.

Surprisingly enough, most analysts, including leading EU officials, have sided unequivocally with the former proposition.

In a new one-pager, C. J. Polychroniou lays out the likely scenarios for the eurozone going forward and casts a skeptical eye on the idea that the future path will or should involve tighter economic and fiscal coordination. The most likely scenario, he argues, is the exit of Greece and possibly Portugal from the eurozone—countries that are really struggling as a result of having given up control over monetary policy.

Read the one-pager here.

Comments

L. Randall Wray | November 17, 2011

Yesterday a group of economists issued a petition to the (new, Berlusconi-free) Italian government. You can read it here. They set out what is mostly good advice based on the premise that Italy should remain in the EMU. Many of my friends signed the petition, but I had to decline. Here is the text of my response to them:

“Dear Friends: I share your concern about the grave situation in Italy. I support much of the petition. In particular, I agree that the ECB must stand ready to buy government debt – indeed, it should announce its intention to drive interest rates for government debt of every member below 3%, and keep buying until it achieves the goal. I also agree that fiscal contraction must be abandoned. There are however three points discussed in the petition on which my views diverge:

a) The solution to the Euro crisis is not to be found in SDRs and the IMF. The ECB can immediately end the problem with government debt. No external help is required, nor should it be sought.

b) The petition should not call for stabilizing debt ratios at current levels. With an ECB backstop, the debt ratio disappears as a matter for concern. It is impossible to say in advance what debt ratio will be required for Italy (and others) to grow back toward prosperity and full employment. There is no point in tying government’s hand to any particular debt ratio.

c) The petition’s statement about “freeing resources” to direct them to promoting full employment is confused. It seems to be based on some loanable funds model. Europe’s problem is that it has far too many “free resources” that are idle – unused capacity: labor, factories – so it does not need to “free” any more. If the petition is discussing “financial resources,” then these are never a scarce resource that needs to be “freed.” I also do not like the statement about taxes. Of course tax evasion should be reduced – but that is a matter of fairness, not “financial resources.”

The first of these points is admittedly minor. The final two points are important. I would like to join my friends in signing the petition but I regret to say that I cannot support arbitrary debt limits (once there is a backstop – and without the backstop then all euro-using governments must reduce their debt ratios tremendously, perhaps to no more than 15% to 20% of GDP), nor a confusing statement on the necessity of freeing resources.”

Comments

Gennaro Zezza | November 16, 2011

Italy is getting a new government today, which is expected to act rapidly to strengthen the Italian growth potential, thus addressing the public debt “problem.” However, it is doubtful that any new government in Italy can succeed in addressing the European financial crisis without concerted action at the European level.

I endorse at least the following portion of this petition: “…we maintain that the new Italian government should rapidly act through the appropriate European institution, with the required determination and political alliances, to obtain a firm and unlimited guarantee by the ECB on the European sovereign debts…”

http://documentoeconomisti.blogspot.com/2011/11/to-parliament-of-italian-republic-to.html

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 15, 2011

Relevant to the question of the legal limits of relying on the European Central Bank as lender of last resort, Tyler Durden observes Jens Weidmann, head of the Bundesbank, defending the narrow view of the ECB’s role in a recent Financial Times interview:

FT: Can you explain why the ECB cannot be lender of last resort?

JW: The eurosystem is a lender of last resort – for solvent but illiquid banks. It must not be a lender of last resort for sovereigns because this would violate Article 123 of the EU treaty [prohibiting monetary financing – or central bank funding of governments]. I cannot see how you can ensure the stability of a monetary union by violating its legal provisions.

I think the prohibition of monetary financing is very important in ensuring the credibility and independence of the central bank, which allow us to deliver on our primary objective of price stability. This is a very fundamental issue. If we now overstep that mandate, we call into question our own independence.

This looks like two separate arguments: (1) lender of last resort activities would violate Article 123; (2) this prohibition of LLR activities (“for sovereigns”) is a good idea anyway, because it preserves ECB independence.

The second argument, if this is what Weidmann intends, would imply that a great many central banks that do have LLR roles, including the Fed, lack sufficient independence. As Brad DeLong argues, this narrow, LLR-less mandate for the ECB represents a radical break with central banking tradition (which, in and of itself, needn’t count as a decisive objection, but it is important to keep all of this in context—in DeLong’s story, Weidmann’s vision for the ECB does not represent some staid, tested, conservative approach). DeLong:

Our current political and economic institutions rest upon the wager that a decentralized market provides a better social-planning, coordination, and capital-allocation mechanism than any other that we have yet been able to devise. But, since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, part of that system has been a central financial authority that preserves trust that contracts will be fulfilled and promises kept. Time and again, the lender-of-last-resort role has been an indispensable part of that function.

Comments

L. Randall Wray | November 14, 2011

(cross posted at EconoMonitor)

For more than a decade, I’ve been arguing that the EMU was designed to fail. It was based on the pious hope that markets would not notice that member states had abandoned their currencies when they adopted the euro, thereby surrendering fiscal and monetary policy to the center. The problem was that while the center was quite happy to centralize monetary policy through the august auspices of the Bundesbank (with the ECB playing the role of the hapless dummy whose strings were pulled in Germany), the center never wanted to offer fiscal policy capable of funding essential spending. (See also Nouriel Roubini’s Eurozone Crisis: Here Are the Options, Now Choose and Marshall Auerback’s piece: The Road to Serfdom.)

Member states became much like US states, but with two key differences. First, while US states can and do rely on fiscal transfers from Washington—which controls a budget equal to more than a fifth of US GDP—EMU member states got an underfunded European Parliament with a total budget of less than 1% of Europe’s GDP. This meant that member states were responsible for dealing not only with the routine expenditures on social welfare (health care, retirement, poverty relief) but also had to rise to the challenge of economic and financial crises.

The second difference is that Maastricht criteria were far too lax—permitting outrageously high budget deficits and government debt ratios.

What? Before readers accuse me of going over to the neoliberal side, let me explain. Most of the critics on the left had always argued that the Maastricht criteria were too tight—prohibiting member states from adding enough aggregate demand to keep their economies humming along at full employment. OK, it is true that government spending was chronically too low across Europe as evidenced by chronically high unemployment and rotten growth in most places. But since these states were essentially spending and borrowing a foreign currency—the euro—the Maastricht criteria permitted deficits and debts that were inappropriate.

Let us take a look at US states. All but two have balanced budget requirements—written into state constitutions—and all of them are disciplined by markets to submit balanced budgets. When a state finishes the year with a deficit, it faces a credit downgrade by our good friends the credit ratings agencies. (Yes, the same folks who thought that bundles of trash mortgages ought to be rated AAA—but that is not the topic today.) That would cause interest rates paid by states on their bonds to rise, raising budget deficits and fueling a vicious cycle of downgrades, rate hikes and burgeoning deficits. So a mixture of austerity, default on debt, and Federal government fiscal transfers keeps US state budget deficits low.

(Yes, I know that right now many states are facing Armageddon—especially California—as the global crisis has crashed revenues and caused deficits to explode. This is not an exception but rather demonstrates my argument.)

The following table shows the debt ratios of a selection of US states. Note that none of them even reaches 20% of GDP, less than a third of the Maastricht criteria. continue reading…

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis