Michael Stephens | December 23, 2011

Japan is the champion nation in terms of budget deficits and government debt relative to GDP. Many have long argued (wrongly) that this is because holders happen to have addresses in Japan. Nonsense. A sovereign government that issues its own currency makes interest payments on its debt in exactly the same manner whether the holder has an address at the South Pole or on Mars: a keystroke to a savings deposit at the central bank. What matters is whether the country issues its own currency.

That is why the little spat between the UK and France—with France insisting that credit agencies ought to down-grade the UK before they downgrade France—is so silly. France can have a debt ratio under 15% of GDP and still be forced to default. The UK can have a debt ratio above Japan’s 200% and still face no chance of involuntary default. That is the beauty and utility of issuing your own currency. France is a currency user and its fate depends on Germany—which is busy sucking up every spare Euro it can lay its greedy hands on. France is no better off than the panhandler on the street corner begging for pocket change—a user of currency, not an issuer.

Read the rest here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | December 22, 2011

The Levy Institute, with underwriting from the Labour Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Workers, has helped design and implement a program of direct job creation throughout Greece. Two-year projects, financed using European Structural Funds, have already begun.

This report by Senior Scholar Rania Antonopoulos, President Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, and Research Analyst Taun Toay traces the economic trends preceding and surrounding the economic crisis in Greece, with particular emphasis on recent labor market trends and emerging gaps in social safety net coverage. Overall, the report aims to aid policymakers and planners in channeling program resources to the most deserving regions, households, and persons; and in devising data collection methodologies that will facilitate accurate and useful monitoring and evaluation systems for a targeted employment creation program.

On its own, the report provides an excellent in-depth portrayal of the evolution of the Greek economy since joining the euro and traces some of the harrowing challenges ahead—particularly in youth employment (the youth labor force participation rate is 20 percent below the OECD average—what’s happening in Greece will truly mark an entire generation).

For those interested in the policy side, the report also provides a solid introduction to the conceptual justification behind a direct job creation program along the lines of Hyman Minsky’s “employer of last resort” idea (beginning on p.33 of the report), while also detailing some of the nuts-and-bolts monitoring and evaluation aspects of making this kind of policy work.

Comments

Michael Stephens | December 20, 2011

Philip Arestis and Malcolm Sawyer have a guest post at Triple Crisis that critiques the latest proposal for a new fiscal compact in the EU (essentially an SGP with more automatic sanctions for those who surpass the 3 percent of GDP budget deficit limit and the annual structural deficit limit of 0.5 percent of GDP). Arestis and Malcom note the asymmetrical restrictions of the compact (there are limits on deficits, but not surpluses) and demonstrate that the deficit limits are entirely too stringent:

The ‘fiscal compact’ assumes that an upper limit of 3 per cent of GDP is consistent with a near balanced structural budget despite the swings in economic activity and associated swings in budget deficits as the automatic stabilisers take effect. As a rule of thumb a 1 per cent fall in GDP below trend leads to around a 0.7 per cent rise in the budget deficit – hence a more than 3 per cent drop in GDP before trend with a structural deficit of 0.5 per cent would lead to a country breaching the limit. Note that this is a drop in GDP below trend – and could come from an actual drop of more like 1 per cent (with a 2 per cent trend growth rate).

Comments

Michael Stephens | December 13, 2011

Micah Hauptman of Public Citizen has drawn from the work of the Levy Institute’s Marshall Auerback and Randall Wray to put together a concise piece that lays out five core critiques of credit default swaps. Among the basic problems he highlights is a flaw-riddled process for determining when a CDS pays off:

… there are no bright lines to determine when a CDS payment is triggered. The system for determining when payments should occur is murky, unregulated, and replete with conflicts of interest. For speculators to cash in on their bets and receive CDS payments, there must be a “credit event.” Failure to pay when due is the most common credit event, however a “credit event” can also occur through bankruptcy, a change in interest rate, a change in principal amount, or postponement of interest or principal payment date. But even within these occurrences, there is considerable legal debate over what constitutes an “event.”

Consider the current financial crisis in Greece. The country has experienced distress due to mounting government debt. European officials recently reached a tentative restructuring agreement. Under the agreement, Greece will undergo a strict austerity plan to regain solvency and Greece’s creditors will receive a reduction in their interests. Whether this restructuring agreement constitutes a “credit event” will likely be contested.

Decisions like this as to whether a “credit event” has occurred are made by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) Determinations Committee—but as Hauptman points out, the ISDA committee includes representatives of financial institutions (some of the largest banks and hedge funds) that often have a stake in whether payments are triggered.

Read Hauptman’s piece here.

For those who are paying attention to the meltdown in Europe, credit default swaps are likely to make a dramatic reappearance. Bloomberg reports, for instance, that European banks are selling CDS on their own member-nation’s debt (via Zero Hedge). Banking on failure indeed.

Comments

Gennaro Zezza | December 12, 2011

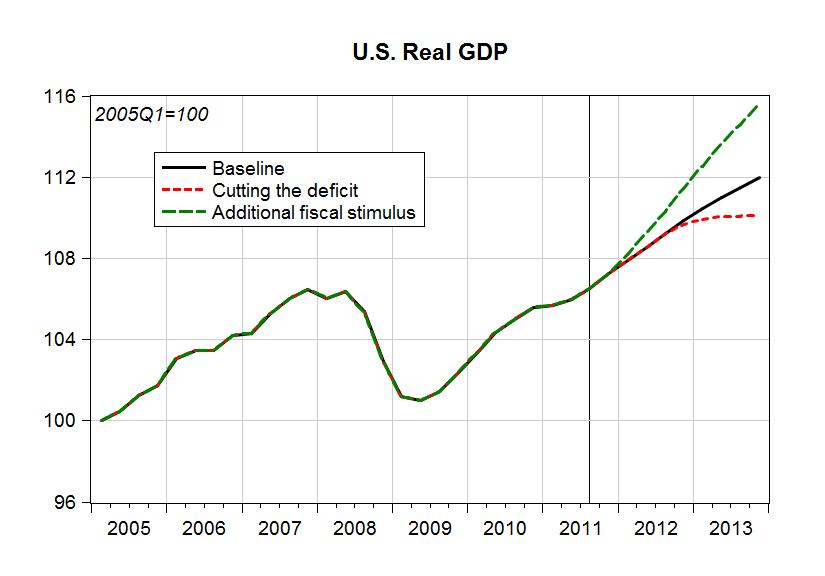

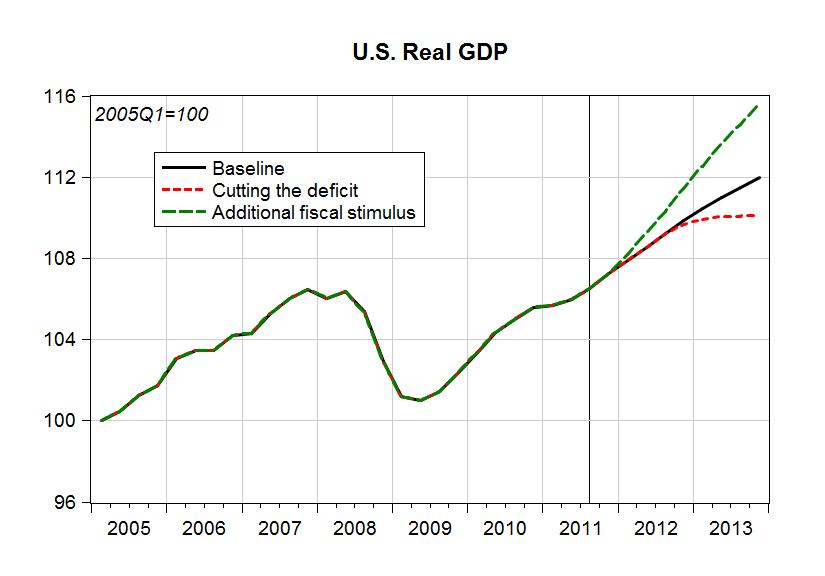

In our latest Strategic Analysis we estimate that a cut in the general government deficit in the United States would have strong adverse effects on unemployment and a relatively smaller impact on the U.S. public debt-to-GDP ratio, since GDP would slow down with a cut in government expenditures and transfers.

A similar strategy of deficit reduction seems to be on the agenda for many eurozone countries; notably Italy, where a new government was recently put in charge to implement unpopular tax increases that the Berlusconi government was not willing to adopt.

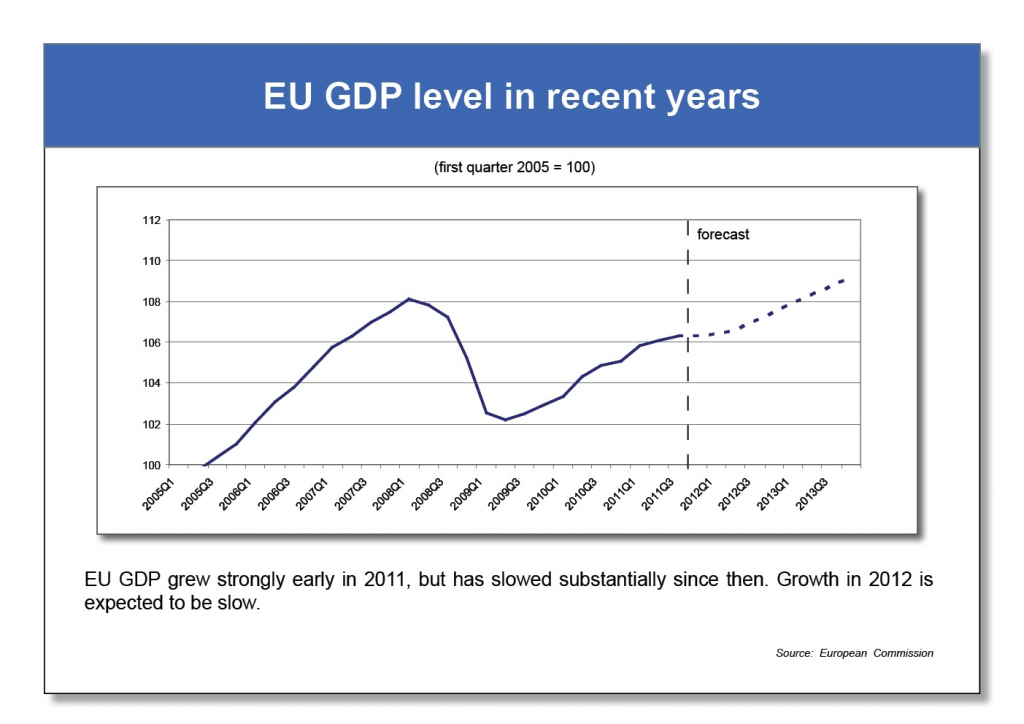

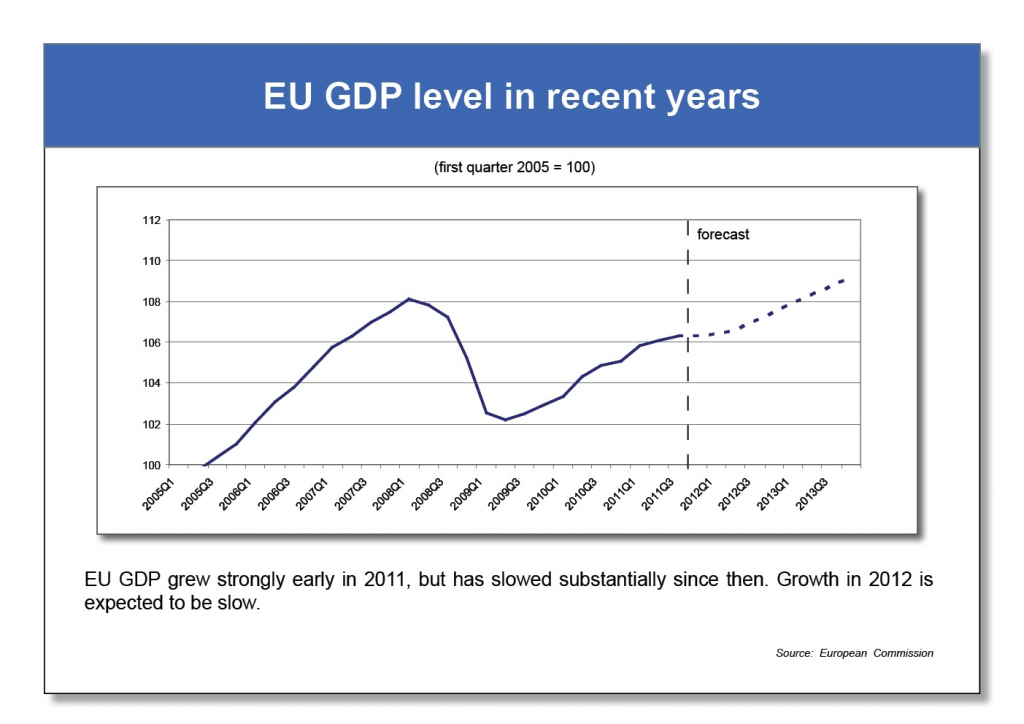

A comparison of our simulation for the U.S. with the European Commission’s for the eurozone may therefore be interesting.

First of all, the United States is now (third quarter of 2011) back to the pre-recession level of output, as measured by real GDP. Using this figure we could say that the recession is behind us, and we can plan for the future (although this is far from true if we look at the unemployment rate!). And in our projections we show that an acceleration in aggregate demand is needed if the unemployment rate is going to be reduced (the green line), while policies to cut the government deficit will lead to stagnation (the red line) and an increase in unemployment.

Let’s look at a similar chart for Europe, taken from a simple synthesis of the new roles for economic governance in the area:

Real GDP in the area is still below its pre-recession level, and stagnating. We would think that European governments would be meeting frequently to discuss how to recover the lost ground in output and employment, but instead they meet with quite a different problem in mind: how to enforce balanced budget rules on national governments. The Italian government, still one of the largest economies in the area, is now passing a bill that will increase taxes substantially, further depressing domestic demand.

What the EU is planning is the wrong policy at the wrong time. And if the multiplier in the EU is similar to what we estimate for the United States, the consequences for the unemployment rate will be substantial.

Comments

Michael Stephens | December 8, 2011

In his latest installment, C. J. Polychroniou surveys the slow motion collapse of the eurozone and the ongoing fragility of the US economy, and insists that underneath it all lies a deeper crisis. What we are witnessing, he suggests, is not just the fallout from the latest banking panic or financial crisis, but a set of symptoms linked to a broader economic malaise: a crisis of advanced global capitalism.

Advanced capitalism had been facing severe structural stresses, strains, and deformations for many years prior to the eruption of the financial crisis in 2007, including overproduction, growing trade deficits, lack of job growth, and elevated debt levels.

Private debt accumulation in the West, which has spiraled out of control, is largely the outcome of wage stagnation. In the United States, wages have remained stagnant since the mid to late 1970s, leading to a new Gilded Age, with renewed claims about the superiority of Darwinian capitalism. At the same time, the poor and working-class populations have come to be seen as a sort of nuisance in the galaxy the rich occupy, with attacks being launched by the rich on their wages and working conditions and the media often carrying out derogatory campaigns against working-class identity.

Read the one-pager here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | December 7, 2011

As Dimitri Papadimitriou has said, the European Central Bank is one of the only institutions that can save the euro project. The commitment alone to making unlimited purchases of member-state debt might do the trick. But as we have seen, there is a lot of opposition to the ECB acting as lender of last resort. Why?

Here are a couple more links on this question:

Paul De Grauwe (“Why the ECB refuses to be a Lender of Last Resort“): it may not (just) be dogma holding the ECB back, but a rational (though, to De Grauwe’s mind, unfortunate) calculation. His analysis suggests the ECB won’t act until the sovereign debt crisis turns into a banking crisis.

Noah Millman (“In the Long Run, We’re All German“): the ECB is engaged in a game of chicken, attempting to secure as much of a commitment to fiscal rectitude and reform as it can before it steps in to stave off a eurozone collapse. (Recent suggestions of a kind of quid pro quo in which a stronger fiscal pact would lay the groundwork for the ECB stepping up as lender of last resort lends some credence to this theory. They should also plant doubts for those who think the ECB’s inaction on this front stems merely from good faith concerns about Article 123-type Treaty obstacles).

Update, Dec. 8: Paraphrasing ECB chief Mario Draghi, today: “Quid pro what? Never heard of it.” (Or more accurately, according to the FT “Mr Draghi made clear that the option of capping government bond yields had not been raised at the governing council meeting.”)

Comments

Michael Stephens |

This is one of the questions Marshall Auerback tackles in a piece at Counterpunch. His answer, as you might expect, is “no.” He also addresses the concern that the ECB risks an impaired balance sheet if it steps up and plays a larger role in buying member-state debt:

… if the ECB bought the bonds then, by definition, the “profligates” do not default. In fact, as the monopoly provider of the euro, the ECB could easily set the rate at which it buys the bonds (say, 4% for Italy) and eventually it would replenish its capital via the profits it would receive from buying the distressed debt (not that the ECB requires capital in an operational sense; as usual with the euro zone, this is a political issue). At some point, Professor Paul de Grauwe is right : convinced that the ECB was serious about resolving the solvency issue, the markets would begin to buy the bonds again and effectively do the ECB’s heavy lifting for them. The bonds would not be trading at these distressed levels if not for the solvency issue, which the ECB can easily address if it chooses to do so. But this is a question of political will, not operational “sustainability.”

So the grand irony of the day remains this: while there is nothing the ECB can do to cause monetary inflation, even if it wanted to, the ECB, fearing inflation, holds back on the bond buying that would eliminate the national [government] solvency risk but not halt the deflationary monetary forces currently in place.

Comments

Michael Stephens | December 2, 2011

Yanis Varoufakis has an interesting exchange with Warren Mosler and Philip Pilkington, responding to their thoughts on the ideal path for a nation intending on breaking away from the euro. The Mosler-Pilkington “plan” (clearly gunning for the Wolfson Prize) is basically this: (1) the government in question starts using the new national currency as a means of payment (paying public salaries, etc.); (2) the government announces that tax payments must be made in that currency. The merit of this approach, they say, is that it is “hands off”:

Should the government of a given country announce an exit from the Eurozone and then freeze bank accounts and force conversion there would be chaos. The citizens of the country would run on the banks and desperately try to hold as many euro cash notes as possible in anticipation that they would be more valuable than the new currency. Under the above plan, however, citizens’ bank accounts would be left alone. It would be up to them to convert their euros into the new currency at a floating exchange rate set by the market. They would, of course, have to seek out the currency any time they have to pay taxes and so would sell goods and services denominated in the new currency. This ‘monetises’ the economy in the new currency while at the same time helping to establish the market value of said currency.

Varoufakis, with a nod to his Levy Institute policy note “A Modest Proposal,” suggests that it’s not too late to save the eurozone project. Although jumping ship in the manner they describe might end up being necessary at some point, says Varoufakis, Mosler and Pilkington are underestimating the severity of the fallout from a euro exit (for the country jumping ship, and for the countries remaining in the boat). Here’s a taste, from Varoufakis: continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 30, 2011

Speaking of balances, late last week Martin Wolf delivered a helpful column (“Why cutting fiscal deficits is an assault on profits,” FT Nov. 24). Wolf writes that if households are cutting back, a government that attempts to reduce deficits while anticipating no substantial changes in net exports must expect corporate surpluses to shrink. But increased investment is unlikely, so: “If the government wishes to cut its deficits, other sectors must save less. … What the government has not admitted is that the only actors able to save less now are corporations. The government’s – not surprisingly, unstated – policy is to demolish corporate profits.”

Wolf is consistently worth the read.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis