Michael Stephens | June 11, 2012

An update on the distressing state of fiscal and monetary policy in the United States and Europe:

Chairman of the Federal Reserve to Congress: “I’d be much more comfortable, in fact, if Congress would take some of this burden from us ….”

Congress to Bernanke: No thanks. And while we’re on the subject, we would be much more comfortable, in fact, if you’d just stop carrying the load entirely. Kindly leave the economy in the ditch right there. Or as Binyamin Appelbaum put it in his NYTimes report:

Republicans on the committee pressed repeatedly for Mr. Bernanke to make a clear commitment that the Fed would take no further action to stimulate growth. “I wish you would look the markets in the eye and say that the Fed has done too much,” Representative Kevin Brady of Texas told Mr. Bernanke. Democrats, by contrast, inquired politely after the Fed’s plans and showed surprisingly little interest in urging the Fed to expand its efforts.

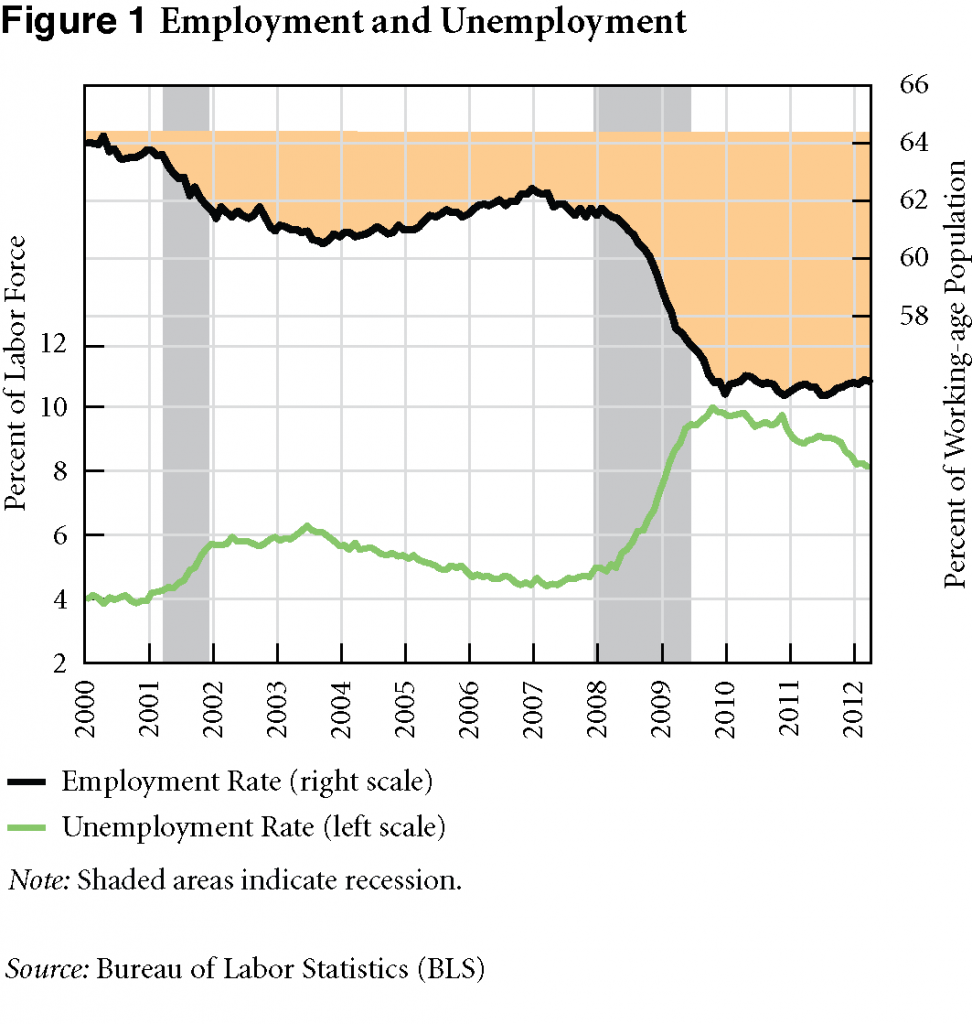

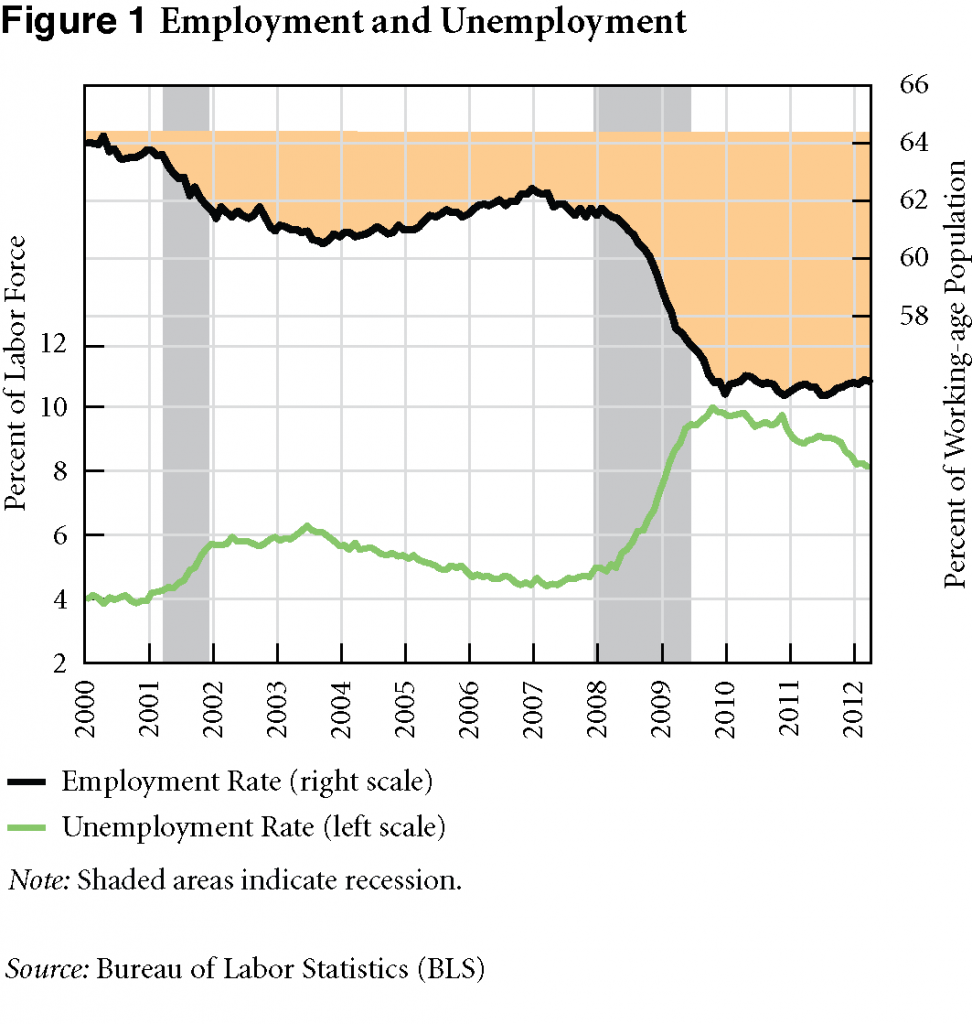

Perhaps the private sector can muddle through on its own? Here’s a graph from the Levy Institute’s Strategic Analysis showing employment and unemployment rates going back to 2000:

To fill the gap in the employment rate represented by that orange area, according to the macro team “the nation needs to find jobs for about 6 percent of the working-age population, or roughly 15 million people. Since the working age population has been growing on average by 2.4 million people per year, or 205,000 each month, job creation that barely reaches a threshold of that number multiplied by the current employment-population ratio of about .59 will not narrow the gap.” Last month the economy generated an estimated 69,000 new jobs. You don’t need your calculator to figure out that won’t narrow the gap.

And how are things in Euroland? continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 30, 2012

News sections are littered with shortcuts for explaining what’s going on in the eurozone, often featuring easy, morally sodden narratives. But the real problem here is not that narratives and other shortcuts are being employed—after all, sometimes the data need a little help. The real problem is that they’re using the wrong narratives.

We’re told more often than not that the reason peripheral countries like Spain are in trouble is that their governments engaged in an irresponsible spending binge and are now reaping the consequences. But in 2007 Spain’s debt-to-GDP ratio was low—a quaint 27 percent of GDP—and had been falling for some time. Likewise, by contrast with the Aesop-flavored conventional wisdom, German ants work 690 fewer hours per year compared to their Greek grasshopper counterparts. But this doesn’t mean morality has no place in an assessment of Europe’s economic woes. Today, for instance, the imposition of austerity and the waste of human potential this is generating—even as austerity fails to summon the “confidence” and growth that was promised and fails to make a significant dent in debt-to-GDP ratios—begs for moral judgement.

And while a technical analysis of the basic setup of the EU and all the imbalances it has generated can get you most of the way toward explaining what’s going on (take a look at the private debt ratios displayed in this graph), this doesn’t mean that domestic political considerations in the peripheral countries haven’t played a part.

But the problem, again, is that the conventional story you’ll find in the press (profligate southern European governments coddling their workers) is problematic. The parts of the EU that are regarded as being in the least amount of trouble also feature some of the more generous social welfare supports. And as C. J. Polychroniou observes in a new policy brief, social democracy of the northern European variety never really took root in southern Europe. Instead, Polychroniou argues, in countries like Greece, Spain, and Portugal, even the left-leaning parties tacitly accepted a neoliberal path, ushering in comparatively regressive policies over the last several decades, including the privatization of public assets and an underinvestment in education and human services (on the whole, public expenditures in these countries are less generous than the EU average). This, combined with political cultures that rely heavily on clientelism, is part of the reason why southern Europe is where it is, according to Polychroniou: regressive policies failed to deliver sustainable growth and have made a bad structural situation even worse.

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 24, 2012

There is no shortage of viable economic solutions for the eurozone. But as Martin Wolf points out in his FT column, once you strike all of the solutions that have been declared politically unacceptable (eurobonds, a stronger EU-level fiscal authority), there aren’t too many policy levers left to pull. One possibility Wolf mentions is to encourage faster adjustment within the eurozone by allowing higher inflation in the core (Germany) than in the periphery—but Germany is unlikely to accept that either.

Instead, we’re left with trying to achieve adjustment through internal devaluation (declining wages in the periphery). How’s that going? C. J. Polychroniou checks in on the progress in his latest one-pager:

The “internal devaluation” policy pursued by Germany, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission can be summed up in a few words: great pain, no gain. The irony of this seems not to have escaped the attention of the Brussels bureaucrats: the Commission’s spring economic forecast, released just a few days ago, observes that “wages in the business sector have been falling in recent quarters but at a pace that was insufficient to help recover competitiveness.” Still, the report injects a note of optimism by stating that “the recent labour market measures are expected to contribute to further significant reductions in labour costs over the next two years.”

…

The Commission also acknowledges that the “current-account deficit . . . remains at an unsustainable level.”

Polychroniou also assesses what the emergence of Syriza means for the future of Greece and eurozone negotiations. Read it here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 22, 2012

Yanis Varoufakis and Stuart Holland have updated their “Modest Proposal” for overcoming the eurozone crisis (they call it version 3.0). They took on the challenge of coming up with proposals for addressing the eurozone’s tripartite crisis (sovereign debt, banking, and underinvestment) in a way that avoids any treaty changes or the creation of new EU institutions. So although turning the eurozone into a “United States of Europe,” with an empowered federal (which is to say EU)-level fiscal authority and a central bank willing and ready to act as a buyer of last resort for government debt might be an ideal solution, there are serious institutional and political obstacles that stand in the way.

These are the three constraints Varoufakis and Holland accepted as fixed elements of the EU’s policymaking landscape:

(a) The ECB will not be allowed to monetise sovereigns directly (i.e. no ECB

guarantees of debt issues by member-states, no ECB purchases of

government bonds in the primary market, no ECB leveraging of the EFSF-ESM

in order to buy sovereign debt either from the primary or the secondary

markets)

(b) Surplus countries will not consent to the issue of jointly and severally

guaranteed Eurobonds, and deficit countries will not consent to the loss of

sovereignty that will be demanded on them without a properly functioning

Federal Europe

(c) Crisis resolution cannot wait for federation (e.g. the creation of a proper

European Treasury, with the powers to tax, spend and borrow) or Treaty

Changes cannot, and will not, precede the Crisis’ resolution.

(The updated version alters the third prong of their proposal, which involves using the European Investment Bank and European Investment Fund to address the growth and underinvestment crisis.)

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 21, 2012

In an interview with Helen Artopoulou that was posted on Capital.gr, Levy Institute president Dimitri Papadimitriou discusses the failure of the austerity policies imposed on Greece and the uncertain future of the euro project.

Q. The political impasse in Greece, largely the outcome of the recent elections, had led to some reconsideration of the austerity policy measures being currently implemented in the indebted countries of the Eurozone. In fact, it seems that a number of public officials have shifted their position, calling now for a growth-oriented economic policy. Given the reality of Greece, how easy is to stir economic growth, and why didn’t the EU follow the growth path to economic recovery in the first place but relied instead on fiscal consolidation and draconian austerity measures?

Economic growth is dependent on public policy aiming at deploying the resources available, that is, labor and capital. Presently, in Greece, there is an abundance of labor, but no capital from either the private or public sectors. It will be some time before the economy becomes friendlier to private investment, markets offering increasing liquidity, and for the private sector to gain confidence in the country’s economic stability. The time horizon for these things to happen will be long so, the responsibility falls on the public sector to do the investing in the key sectors of the Greek economy. But the public sector is on the brink or bankrupt, and in effect restricted by the EU, ECB and IMF in investing for growth. When they call for a growth-oriented economic policy in response to the overwhelming election results in favor of the anti-austerity platform, they simultaneously insist on the implementation of the imposed austerity. This joint policy prescription, that growth and austerity can coexist, is the new “austerian” economics—a new frontier of economic nonsense. North European leaders believe that all member states in the Eurozone can be similar to Germany’s competitive export-led growth economy. But Germany’s competitive advantages that yield intra Eurozone better trade balances are dependent on other Eurozone’s countries worse balances.

Austerity programs were imposed, first, to discipline the eurozone’s profligate citizens and, second and most importantly to calm the financial markets, both of which have failed miserably. The medicine of austerity has worsened the patient’s condition and markets, as has been observed time and time again, have a mind of their own.

Q. Greece is facing once again the prospect of a forceful exit from the eurozone. How likely is this frightening scenario and is it manageable? Also, would it be as disastrous for the country as most people fear it would be?

Read the whole thing here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | May 10, 2012

The recent Greek elections, which did not produce a party (or a viable coalition) with a majority in Parliament, have occasioned a lot of excited speculation about Greece either leaving the eurozone or being nudged out. Dimitri Papadimitriou comments today in a CNN Money piece about this possibility and offers a slightly more sober assessment, suggesting there are signs that European leaders may give Greece more leeway. Read it here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | April 24, 2012

In a radio segment for Ian Masters’ “Background Briefing,” Dimitri Papadimitriou speculates that Germany might just end up being the eurozone country that decides it’s not worth staying in the union.

Germany, says Papadimitriou, has boxed itself in such that, as one of the only eurozone countries that’s growing, it must ultimately bear the major responsibility for the rescue packages that are being offered for troubled countries like Portugal, Greece (x2), and Ireland—and that may soon have to be put in place for Spain. While an exit is unlikely as long as Angela Merkel is in power, Papadimitriou reminds us that she’s up for re-election next year, and the winds of political change have started blowing in Europe.

Listen to or download the whole interview here (Papadimitriou’s segment begins at minute 37, with the discussion turning to German exit around 44:30): http://archive.kpfk.org/mp3/kpfk_120423_170004dbriefing.MP3

Comments

Michael Stephens | April 23, 2012

The Washington Post is casually informing its readers that the eurozone’s austerity programs are really aimed at addressing all that government profligacy everyone knows was rampant in the run up to the crisis.

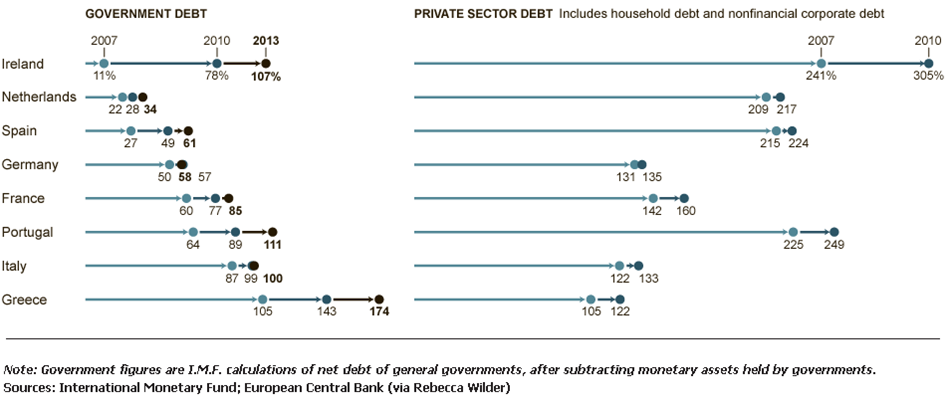

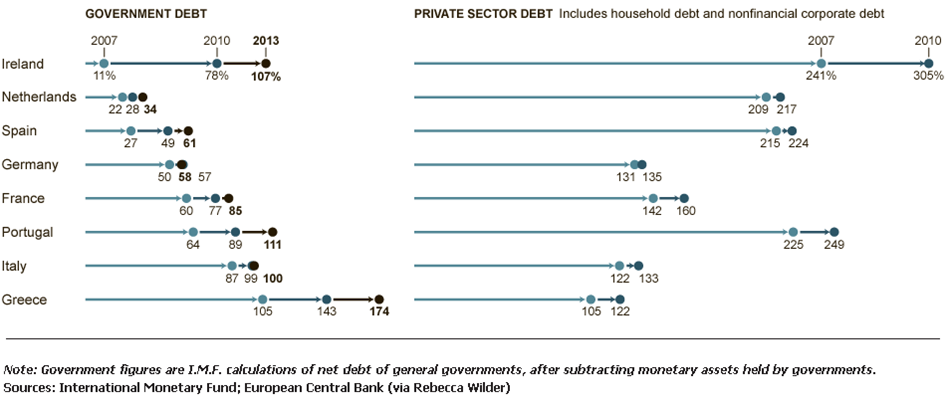

This seems like another good opportunity to post this chart, showing net debt as a percentage of GDP in some key eurozone countries, pre and post crisis (click to enlarge):

As you can see, for almost all of these countries the crisis was largely a cause of rising public debt ratios, not an effect. Spain, which as the Post article notes is the latest country on the eurozone hot seat, had a public debt-to-GDP ratio of 27 percent in 2007 (and as Dean Baker points out, Spain was running a budget surplus). Reckless!

If you’re really looking for a debt-related problem in the buildup to the crisis, take a glance at the right-hand side of the chart. There you’ll see private debt ratios at significantly higher levels. For more on this and the real story behind the problems in the eurozone, see this policy brief by Dimitri Papadimitriou and Randall Wray (short version here).

Update: Paul Krugman adds more (responding to a piece in the FT by Kenneth Rogoff) by posting a graph showing the trend in public debt ratios in the eurozone periphery during the 2000s. As you can see, 2007 represents the trough in a long, steady pre-crisis decline in public debt-to-GDP ratios among the GIPSI countries. This is the very time period in which we are being told that government budgets were “ballooning” out of control.

Comments

Michael Stephens | April 18, 2012

Although some considered (or pretended to consider) the eurozone crisis to have been “solved” with the last Greek bailout/bond swap, reality “begs to differ,” says C. J. Polychroniou. In his latest one-pager, Polychroniou provides an update on the status of “eurozone crisis 2.0” as the spotlight shifts to Spain, Portugal, and Italy:

The eurozone crisis isn’t back: it never left. It merely went into a very brief hibernation, as the world watched Europe’s leaders trying out various fixes for the wrong crisis. No matter how much cheap money the ECB provides or how high the EC “firewall” rises, Europe’s economic sickness will not be cured without massive government intervention to get the regional economy rolling again.

Read the whole thing here.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

In a Bloomberg article that details how banks in the eurozone periphery have begun carrying increasing proportions of the debt issued by their own nations’ governments (while banks in the core have reduced their holdings of peripheral sovereign debt), Dimitri Papadimitriou comments on some of the consequences of this “national fragmentation of credit”:

“If there’s a private-sector restructuring of Portuguese sovereign debt, then Portugal’s banks will need a bailout like Greek banks did,” Dimitri Papadimitriou, president of the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, said in an interview.

In Spain, stronger banks such as Banco Santander SA (SAN), the country’s largest lender, can handle losses from their sovereign holdings, while weaker savings institutions stung by soured real estate loans will need help, Papadimitriou said. Italian banks probably are buying more of their country’s debt because they can sell it to retail customers who still have an appetite for the securities, he said.

Read the article here.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis