Scholars at the Levy Institute have supported the creation of an employer-of-last-resort (ELR) program in the United States for many years. Such a program would provide a government job to any American who needed one and met a few basic requirements. (This readable policy note, along with many other Levy publications, explains the case for ELR programs.) So far, the government has created many jobs since the passage of the stimulus package, but the unemployment rate remains at 9.5 percent. Many forecasters are now predicting that the overall unemployment rates for 2010 and 2011 will both exceed 9 percent

Children are among the groups deeply affected by recessions. For example, a government report issued last November found that over one million children sometimes went hungry in 2008, which represented a large increase over the previous year. Also, in a recent article, Katherine Newman and David Pedulla discuss how this recession has had an uneven impact, hitting groups like young people just entering the labor force especially hard.

Programs that helped the poor in times like these were weakened greatly in 1996, when President Bill Clinton somewhat reluctantly signed a welfare reform bill that was not what he had hoped for, saying that it was the country’s “last best chance” for reform. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act set time limits for receiving welfare benefits, and converted the program from one that provided grants to all qualified families to one that came in the form of a grant of a fixed amount to each state. In passing the bill, leaders intended to expand work requirements for welfare benefits, but in practice many were not able to get work, appropriate training, and/or child care. The bill followed many years of reforms at the state and federal levels, some of which had enabled welfare recipients to obtain job training or to raise their incomes substantially by putting in more hours of work.

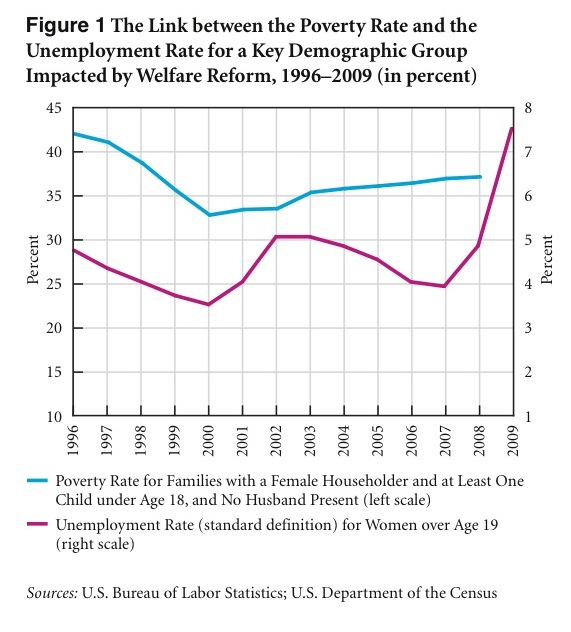

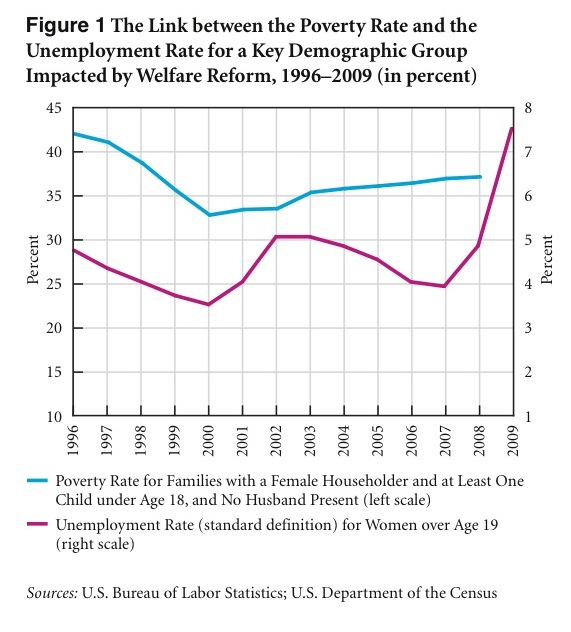

When the 1996 welfare reform effort took effect, many observers expected an eventual rise in homelessness and poverty, particularly among single-parent families. These effects seemed to have been avoided at first, and indeed poverty rates seemed to be falling as states implemented the new law. Many observers noted, however, that the job market was relatively tight during the late 1990s. The graph below (click on it for a larger view) shows two data series: unemployment for women over 19 years old and poverty rates for families with a female adult, children under age 18, and “no husband.”

The idea is to show how poverty for this group is related to the strength of the job market. Note that as welfare reform went into effect in the late 1990s, the unemployment rate for women was falling, mostly because of a booming economy. This trend helps to explain the fall in the poverty rate shown on the left side of the figure. Then, after the stock-market crash of 2000 and the recession that followed, the unemployment rate shown in the figure rose. It dropped a bit during the subsequent recovery, but then climbed again, reaching 4.9 percent in 2008. This reduction in demand for workers partially explains the steady rise in poverty that occurred during the same period, to more than 37 percent in 2008. Fortunately, improvements in the earned income tax credit (EITC) program probably helped to contain increases in poverty rates during this period. Of course many other factors affect poverty rates, some related to the business cycle and some not.

Unfortunately, as the graph shows, the unemployment rate for women more than 19 years of age rose again in 2009, by 2.6 percentage points—a big increase. The Census Bureau has not released poverty rates for that year, but this analysis shows that there is very good reason to believe that the new data will show that the rise in most poverty rates continued in 2009. Moreover, monthly data for this year show that the unemployment rate for women over 19 continued to rise in 2010 and stood at 7.9 percent as of June. Last month’s employment data will be released later this week. This information suggests that job creation efforts and other initiatives to help the unemployed and underemployed should be on the increase and not on the wane.

ShareThis

ShareThis