January Employment Report: Broader Effects of Seasonal Adjustment

Two Fridays ago, I blogged about some newly released Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data from a monthly household survey. I was surprised later to see that Multiplier Effect was one of only a handful of websites to mention that non-seasonally adjusted data showed vastly different and perhaps more disturbing results than the widely reported deseasonalized numbers: a flat unemployment rate, a sharp fall in employment, and a rise in the number of people unemployed. All of the numbers I discussed were based on traditional concepts of unemployment, which have been familiar to newspaper readers for decades.

It is important to put such survey results in context, and I have now had time to finish putting together some further information on the effects of seasonal adjustment on the numbers released early this month. While the standard version of the unemployment rate is widely reported and debated, it does not include potential workers who are not considered to be in the labor force because they have not recently been looking for work. If the labor market were stronger, most of these individuals would almost certainly return to the workforce and find work. Hence, it is interesting to look at a broader measure of unemployment that includes at least some of those out of workforce who want to work, but have not recently been searching for a job.

One such statistic is the BLS’s own U-4 measure of “labor underutilization,” which includes those deemed to be “discouraged workers,” in addition to the unemployed. The seasonally adjusted version of U-4 dropped from 10.2 percent in December to 9.6 percent in January. In contrast, the non-seasonally adjusted version of this index rose from 9.9 percent to 10.4 percent, according to the BLS. Hence, the story we have told in blog entries over the last two weeks also seems to have some implications for a more comprehensive measure of the human cost of weakness in the labor market.

The simple methodology that I used in my most recent post on the BLS report to calculate the impact of seasonal adjustment on the month-to-month change in the unemployment rate can be extended to a broader but unofficial index. This time, my answer will be somewhat less exact, because we do not have complete information about the potential impact of the 2011 adjustments to BLS population estimates on my new calculations .

Using data from Table A-1 of the BLS news release, as well as partial information on the effects of population adjustments on the January data from Table C of the release summary, we can find the contribution of seasonal adjustment to the apparent change in the following seasonally adjusted makeshift unemployment index:

number unemployed + number out of the labor force who want to work

divided by

labor force + number out of the labor force who want to work

The BLS does not separately report this statistic to our knowledge, but it is similar in spirit to several other alternative gauges of labor underutilization reported in Table A-15 of the employment report. Hence, we report our findings with the caveat that the BLS certainly might not endorse the use of this improvised measure.

What we find is interesting: seasonally adjusted BLS numbers from table A-1 imply that our broad unemployment index dropped from 13.0 percent in December to 12.7 percent last month. These are large numbers indeed. However, removing the effects of seasonal adjustment on the underlying raw numbers, the broad index probably would have risen by at least .9 percent, from 13.0 percent in December to between 13.9 and 14.0 percent. Hence, using a similar methodology to last week’s post, one finds that the effect of seasonal adjustment on the change in the broad unemployment measure is even greater than the corresponding effect on the change in the usual measure.

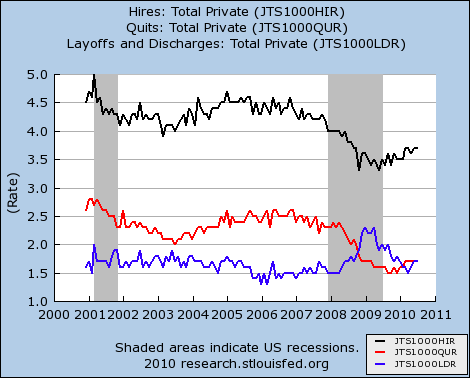

By the way, other data in the recent government report suggest that this difference between seasonally adjusted and non-seasonally unadjusted figures can largely be accounted for by temporary layoffs whose impact on the data was removed by adjustment procedures. In other words, many workers were laid off last month, but were not counted in the most widely reported January unemployment figures, because large numbers of layoffs are not unusual for that time of year.

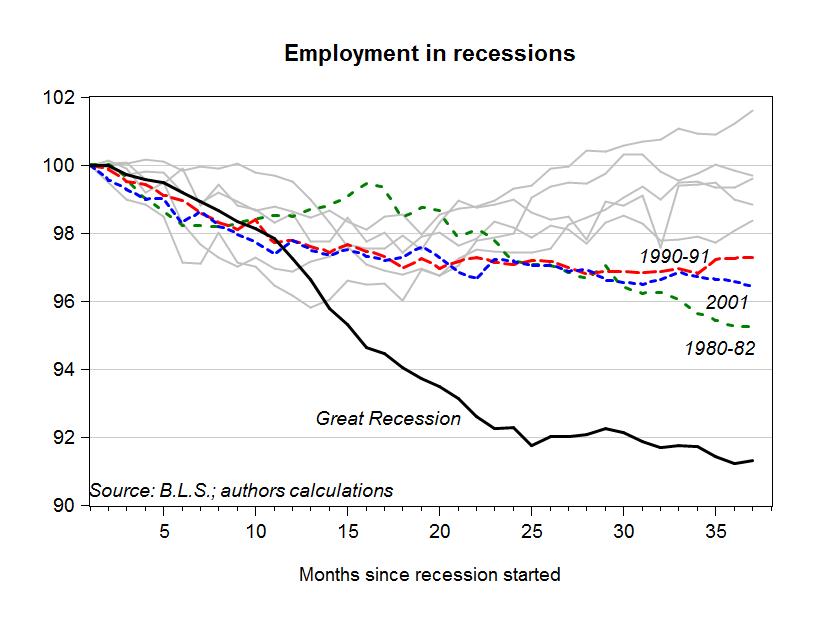

In fact, the historical record shows that the effects of BLS seasonal adjustment procedures are often especially large for the January release, resulting in substantial downward statistical adjustments to the recorded change in the unemployment rate from the previous December. This effect is not often noted in the media, though non-seasonally adjusted BLS figures are made available in the same report as the headline unemployment rate. The blog seekingalpha wrote about this phenomenon last winter. The figure at the top of this post is similar to a graphic appearing in that blog entry.

Edited slightly for clarity and readability Feb. 16 at 12:11 pm.

ShareThis

ShareThis