Michael Stephens | September 12, 2011

The AJA is DOA. Via Politico: “House Republicans may pass bits and pieces of President Barack Obama’s jobs plan, but behind the scenes, some Republicans are becoming worried about giving Obama any victories — even on issues the GOP has supported in the past.”

For Thomas Masterson’s extensive treatment of the proposed American Jobs Act (“equal parts weak tea and bitter pill”), see here.

Update: 50% DOA. Or as Miracle Max put it: “Whoo-hoo-hoo, look who knows so much. It just so happens that your friend here is only mostly dead.”

Comments

Thomas Masterson | September 9, 2011

Well, I commented last night on President Obama’s speech to Congress on WGXC, my local radio station. I thought it worth putting down my thoughts on silicon, since I’ve already done all the thinking about it.

First of all, I thought that the delivery was one of the better that I’ve heard from President Obama since he took office. It reminded me more of candidate Obama. Maybe that’s because this speech, more than the official announcement that he was running for re-election a while back, was the kick-off to his re-election campaign. He had that whole preacher cadence down, punctuating sections of the speech with the phrase “that’s why you should pass this bill now.” A nice touch, but one that was clearly not directed at the politicians in front of him, many of whom wouldn’t support kibble for kittens if it was an Obama proposal.

Moving on to substance is a bit depressing. The American Jobs Act is equal parts weak tea and bitter pill. The weak tea is that as a job creation proposal it does too little, too ineffectively. Much of the proposal the President outlined in the speech sounds a lot like the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the stimulus passed early in 2009. I will talk about that bill’s effectiveness in a bit, because I think a lot of people think very lazily about how to assess that policy’s impact. But the parts are all there: lots of tax cutting; state aid; unemployment insurance; and infrastructure spending. There is also some mortgage finance relief thrown in for good measure.

Tax cuts will be welcome to most people, of course. Who doesn’t want more of their paycheck going directly into their pockets (other than Warren Buffet, of course)? The proposal to cut payroll taxes in half is great in a couple of ways. It will add some stimulus to the demand for goods and services (people will buy more stuff if they get their hands on a bigger chunk of their paychecks). And the payroll tax is one of the more regressive federal taxes, since people pay a flat rate on their first $100K or so of wage and salary income and nothing above that cap, which means that people who make less than $100K (most of us) put a bigger percentage of our salaries into the Social Security system than those who make more.

The employer reduction in the payroll tax isn’t going to be as helpful. Some small business owners will see that as a small bump to their bottom line, but it certainly isn’t going to create a lot of jobs. Nor will the tax credits for hiring the long-term unemployed or veterans, although those are certainly worthy targets for encouraging employment. But businesses aren’t making hiring decisions based on the tax implications of hiring more workers. Certainly, they take taxes they have to pay into account, but these are a small portion of the cost of hiring someone. The point is that businesses aren’t hiring people because there is not enough demand for goods and services in the economy. Until demand for the stuff businesses produce or provide goes up, hiring will remain slow.

State aid is a simpler case to make. continue reading…

Comments

Thomas Masterson | September 7, 2011

In a post on Ezra Klein’s blog entitled “The recession’s gender gap: from ‘man-cession’ to ‘he-covery’,” Suzie Khimm notes that the recovery is happening for men but not so much for women. She quotes an Institute for Women’s Policy Research paper that refers to our research, found in this policy brief. Early childhood education and home health care represent great opportunities for improving quality of life for the care recipients as well as for the people who would become employed under these proposals. I will be listening for some mention of them by President Obama tomorrow night.

Comments

Thomas Masterson | August 31, 2011

All to the same place? You might be excused for thinking so after perusing Tyler Cowen’s post Why didn’t the stimulus create more jobs?, but you would be wrong. First let’s look at Cowen’s post for some obvious red flags. About the number of people hired using stimulus funds who were already employed, Cowen says:

You can tell a story about how hiring the already employed opened up other jobs for the unemployed, but it’s just that — a story. I don’t think it is what happened in most cases, rather firms ended up getting by with fewer workers.

OK, so the substance of this is he doesn’t like one story, he prefers another. I quite understand why, Cowen being who he is. I happen to like the other story, myself. However, one might want actual proof rather than preferences (dear as they are to neo-classical economists).

A second point requires reading the two studies Cowen refers to. Cowen says that “There are lots of relevant details in the paper but here is one punchline: ‘hiring people from unemployment was more the exception than the rule in our interviews.'” Interesting choice. Especially given that the first bullet point in their summary of results is: “ARRA funds led to worker hiring and retention.” And that is the point after all. The question of whether the ARRA funds went to directly hire unemployed workers or not is mostly beside the point.

The question that matters in job terms is: how many more people were employed because of the ARRA spending than would have been without it? It’s a question we can’t know the answer to, because we will never know what would’ve happened without the stimulus. The insinuation in Cowen’s post is that for a variety of reasons the stimulus wasn’t that stimulative. The proof offered is that Cowen doesn’t think workers hired away from other jobs were replaced, or that (from the paper itself, now) wages were mandated to be too high: “38.2 percent [of “organizations required to pay prevailing wages”] thought that they could have hired workers at wages below the Davis-Bacon prevailing wage.” The latter point misses the point of stimulus: its multiplier effect (where have I seen that phrase before?). The number of jobs directly created or saved by the stimulus isn’t the whole story. Those workers, having non-zero rather than zero money in their pockets, will spend more, saving or creating other jobs, and so on.

A final “damning” conclusion from the paper: “[h]iring isn’t the same as net job creation.” Indeed. But net job creation is never actually dealt with in the paper, let alone net job creation/saving relative to no stimulus. For an estimate of job creation under the first three years of the stimulus, you could look at this paper (self-serving, isn’t it?).

I sometimes wonder whether folks who think stimulus spending has little to no effect (or a negative effect!) on employment think the money is just piled up on the White House lawn for President Obama to (gleefully, I’m assuming in this fantasy) toss a lit match onto.

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 26, 2011

If you believe the US political system is incapable of handling counter-cyclical policy and that we need to rely on automatic stabilizers, this CBPP graph is depressing:

In other words, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (the result of the 1996 “welfare reform”), for whatever its other merits might be, has not been particularly sensitive to increases in poverty. As the number of needy families grew during the recession, the TANF rolls barely budged. More here.

Comments

Greg Hannsgen | August 22, 2011

The early phases of the 2012 presidential election season have already brought us a great deal of debate on fundamental economic policy issues. Greg Ip, in the Washington Post‘s PostOpinions, writes about the views of a number of Republican candidates (pointer via Economist’s View). Are they believers in the “voodoo economics” that many recall from past elections–tax cuts for the wealthy that supposedly spur growth and reduce deficits and at the same time?

Not according to Ip. He describes a risky, and somewhat novel, approach to economic policy emerging in this year’s political rhetoric. This approach rejects policies that have reduced the severity of the business cycle since the Great Depression. Ip skewers the politicians’ critique of these Keynesian policies, which blames the country’s economic problems on excessive government action:

Many Republicans consider the tepid economic recovery an indictment of Keynesianism, and use the word as an epithet, as in “Keynesian Utopia” (Sarah Palin) or “Keynesian bubble” (Ron Paul). They argue that aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus have made things worse by generating uncertainty among firms and investors, and that austerity would put things right.

They almost surely have it wrong. Uncertainty about fiscal and monetary policy was also rampant in the early 1980s: Taxes were cut and raised repeatedly and the Fed tried, then abandoned, efforts to target growth in the money supply instead of interest rates. Yet after a sharp recession in 1981-82, the economy took off, primarily because the recession had been induced by high interest rates and, once rates fell, demand sprang back.

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 16, 2011

Joe Nocera’s musings about Kurzarbeit aside, it is not the case that what we need right now are more and newer ideas for increasing growth and jobs. We do not have a scarcity of such policy ideas. What we are lacking are the political institutions that would allow us to carry any of them out. Our policy problem is a political problem.

It is remarkable how much of our lingering economic malaise can be attributed, not to the inherent thorniness of the problems we face, but to the misaligned incentives of our political system. As Greg Hannsgen pointed out in a recent post, there is no reason to believe that the United States government has suddenly been rendered unable to pay its debts as they come due. Rather, the danger appears to be that the political system (or at least an empowered minority of it) will simply refuse to do so.

This is a recurring pattern. Take the case of growth and employment. The real resources necessary for a higher level of economic activity and employment are there, sitting idle. Unfortunately, most of the textbook policy solutions lay equally idle; discarded and now beyond the realm of political possibility. We have the productive capacity, but through political choice or obstruction we are simply refusing to use it.

Under these circumstances, what should policy writers and economists do? continue reading…

Comments

Gennaro Zezza | August 9, 2011

While public discussion in the last several weeks has been absorbed by the debt ceiling saga, and in the coming weeks will probably focus on the S&P downgrade, employment (or lack thereof) is still a major problem. Our employment problem is one of the main factors contributing to a sizeable government deficit and growing public debt.

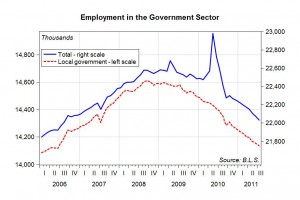

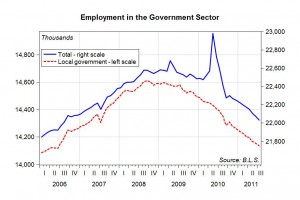

For all those who think that government has expanded wildly during the recession as a result of the fiscal stimulus, think again. The chart above shows that of the 7.3 million jobs lost since November 2007, 300,000 of those were lost in the government sector; more specifically in local government, which accounts for about 64% of the employment in the government sector. Local governments have to run a balanced budget, and when a recession hits and their tax receipts decline, they have to cut expenses—which means fewer jobs. If the federal government were to embrace similar balanced-budget policies, its ability to support a struggling economy would be severely curtailed. It would not only be unable to create jobs directly; it would struggle to even maintain its existing workforce.

The chart below shows one measure of the employment rate, computed as a percentage of the working-age population. This share rose in the post-WWII period with the increase in the female participation rate. It stabilized in the twenty years before the Great Recession at around 63%, dropped to 58% during the recession, and has remained roughly stable in the last ten months. To see what the prospects are for employment going forward, we have made some simple calculations. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 3, 2011

Following up on a previous item, Macroeconomic Advisers have updated their analysis in response to the most recent debt ceiling deal. The results: no good news, and some serious uncertainty in the probable effects on growth (though not the sort of “uncertainty” the conventional wisdom is persistently telling us we should care about).

In 2012, they estimate that the fiscal drag resulting from budget cuts is likely to hover around 0.1 percentage points. If that strikes you as a minor blip, note that they have not included multiplier effects in their estimates. The Economic Policy Institute, using standard multipliers, estimate that the ultimate damage in 2012 would amount to a reduction of 0.3 percentage points in GDP, or, if that still doesn’t get your attention, around 323,000 fewer jobs.

When adding in the effects of the expiration of the unemployment insurance extensions (528,000 fewer jobs) and the payroll tax cuts (972,000 jobs), EPI suggest that we should expect the economy to shed somewhere on the order of 1.8 million jobs as a result of these policy choices.

While the administration, via Tim Geithner op-ed, signaled today that it would like to extend both the unemployment insurance and payroll tax cut measures, as well as to initiate new infrastructure investments, it takes a certain amount of imagination to see how any of these measures—even the extension of tax cuts—could get through Congress in the current climate.

If that still doesn’t faze you, consider that in 2013, as a result of the debt ceiling deal, things really start to get dicey. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | July 29, 2011

The economy grew at an unflattering 1.3% annual rate in the second quarter, while first quarter GDP growth has been revised downwards to a wretched 0.4%.

Against the backdrop of these abysmal numbers, the US government appears poised to do its best to make matters worse. Even if the debt limit negotiations generate an agreement, this is likely to entail a rather substantial anti-stimulus over the next couple of years. When combined with the expiration of the unemployment insurance extensions and of last year’s payroll tax cut, one can expect the US government to shortly be withdrawing somewhere on the order of a quarter of a trillion dollars from the economy.

The forecasting group Macroeconomic Advisers estimates that, as a result of the possible debt limit deals alone, GDP will be roughly 0.1 percentage points lower next year, and up to almost 0.5 points lower in 2013.

Again, it is useful to remind ourselves that this is purely self-inflicted. There is no requirement that budget savings be produced equal to the value of the rise in the debt ceiling—this is entirely a result of political strategy and political demands. And aside from the debt limit negotiations themselves, there is not much of a case to be made that reducing deficits in the near term in any way solves an emergent economic problem. Interest rates are low by historical standards and inflation remains in check. What’s more, key indicators show little evidence of expectations of increasing inflation down the road (for more on this, see the Levy Institute’s Public Policy Brief on the health of the recovery, containing useful numbers on measures of inflationary expectations).

Debt and deficits are not some moral stain on the nation; they are simply a matter of economic accounting. And as such, with regard to the idea of reducing debt and deficit levels we must always ask: what problem is this supposed to solve? In a recent working paper, Levy Institute Research Associate Mathew Forstater provides a helpful primer (pp. 6-13) on three different ways of understanding the potential economic issues surrounding government debt and deficits: from a “deficit hawk,” “deficit dove,” and “functional finance” approach.

MS

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis