A number of prominent economists have signed a letter calling for more economic stimulus from the United States government in order to put people back to work. Levy senior scholar James K. Galbraith and two other well-known Keynesians chose not to participate, and issued this comment explaining why.

A statement from Paul Davidson, James Galbraith and Lord Skidelsky

We three were each asked to sign the letter organized by Sir Harold Evans and now co-signed by many of our friends, including Joseph Stiglitz, Robert Reich, Laura Tyson, Derek Shearer, Alan Blinder and Richard Parker. We support the central objective of the letter — a full employment policy now, based on sharply expanded public effort. Yet we each, separately, declined to sign it.

Our reservations centered on one sentence, namely, “We recognize the necessity of a program to cut the mid-and long-term federal deficit… ” Since we do not agree with this statement, we could not sign the letter.

Why do we disagree with this statement? The answer is that apart from the effects of unemployment itself the United States does not in fact face a serious deficit problem over the next generation, and for this reason there is no “necessity [for] a program to cut the mid-and long-term deficit.”

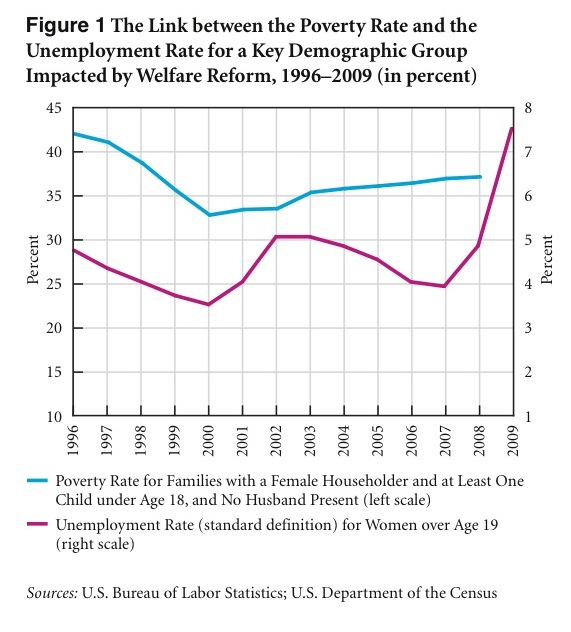

On the contrary: If unemployment can be cured, the deficits we presently face will necessarily shrink. This is the universal experience of rapid economic growth: tax revenues rise, public welfare spending falls, and the budget moves toward balance. There is indeed no other experience in modern peacetime American history, most recently in the late 1990s when the budget went into surplus as full employment was reached.

We agree that health care costs are an important issue. But health care is a burden faced by both the public and private sectors, and cost control is a job for health policy, not budget policy. Cutting the public element in health care – Medicare, especially – in response to the health care cost problem is just a way of invidiously targeting the elderly who are covered by that program. We oppose this.

The long-term deficit scare story plays into the hands of those who will argue, very soon, for cuts in Social Security as though these were necessary for economic reasons. In fact, Social Security is a highly successful program which (along with Medicare) maintains our entire elderly population out of poverty and helps to stabilize the macroeconomy. It is a transfer program and indefinitely sustainable as it is.

We call on fellow economists to reconsider their casual willingness to concede to an unfounded hysteria over supposed long-term deficits, and to concentrate instead on solving the vast problems we presently face. It would be tragic if the Evans letter and similar efforts – whose basic purpose we strongly support – led to acquiescence in Social Security and Medicare cuts that impoverish America’s elderly just a few years from now.

Paul Davidson is editor of the Journal of Post Keynesian Economics and author of The Keynes Solution.

James K. Galbraith is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author of The Predator State.

Lord Robert Skidelsky is the author, most recently, of Keynes: The Return of the Master.

ShareThis

ShareThis