The American Jobs Act. sigh.

Well, I commented last night on President Obama’s speech to Congress on WGXC, my local radio station. I thought it worth putting down my thoughts on silicon, since I’ve already done all the thinking about it.

First of all, I thought that the delivery was one of the better that I’ve heard from President Obama since he took office. It reminded me more of candidate Obama. Maybe that’s because this speech, more than the official announcement that he was running for re-election a while back, was the kick-off to his re-election campaign. He had that whole preacher cadence down, punctuating sections of the speech with the phrase “that’s why you should pass this bill now.” A nice touch, but one that was clearly not directed at the politicians in front of him, many of whom wouldn’t support kibble for kittens if it was an Obama proposal.

Moving on to substance is a bit depressing. The American Jobs Act is equal parts weak tea and bitter pill. The weak tea is that as a job creation proposal it does too little, too ineffectively. Much of the proposal the President outlined in the speech sounds a lot like the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the stimulus passed early in 2009. I will talk about that bill’s effectiveness in a bit, because I think a lot of people think very lazily about how to assess that policy’s impact. But the parts are all there: lots of tax cutting; state aid; unemployment insurance; and infrastructure spending. There is also some mortgage finance relief thrown in for good measure.

Tax cuts will be welcome to most people, of course. Who doesn’t want more of their paycheck going directly into their pockets (other than Warren Buffet, of course)? The proposal to cut payroll taxes in half is great in a couple of ways. It will add some stimulus to the demand for goods and services (people will buy more stuff if they get their hands on a bigger chunk of their paychecks). And the payroll tax is one of the more regressive federal taxes, since people pay a flat rate on their first $100K or so of wage and salary income and nothing above that cap, which means that people who make less than $100K (most of us) put a bigger percentage of our salaries into the Social Security system than those who make more.

The employer reduction in the payroll tax isn’t going to be as helpful. Some small business owners will see that as a small bump to their bottom line, but it certainly isn’t going to create a lot of jobs. Nor will the tax credits for hiring the long-term unemployed or veterans, although those are certainly worthy targets for encouraging employment. But businesses aren’t making hiring decisions based on the tax implications of hiring more workers. Certainly, they take taxes they have to pay into account, but these are a small portion of the cost of hiring someone. The point is that businesses aren’t hiring people because there is not enough demand for goods and services in the economy. Until demand for the stuff businesses produce or provide goes up, hiring will remain slow.

State aid is a simpler case to make. States lose revenue during recessions: fewer people working means lower income tax receipts, and lower sales tax receipts as well, as people economize. And state expenses for things like Medicaid naturally go up during recessions, since people are poorer. In addition, in many states, pension funds were hit hard by the financial crisis (remember that?), meaning that, because of the actions of fraudulent bankers, states had to come up with extra money for their pension systems right when their tax revenues were tanking. Those are the reasons why in every state for the last few years, budgets have been a huge problem: it’s not spending, it’s revenue. So state aid is a simple thing the Federal government can do to prevent layoffs of teachers, policemen and firefighters. Too bad Congress cut half of it out of the ARRA. That didn’t have any bad consequences, did it? I’m sure Congress wouldn’t make the same mistake again (by the way, that was sarcasm).

Infrastructure spending was a good idea in 2009 and it’s still a good idea today. Though it isn’t a super-fast and effective way to get people back to work, it is better than nothing. It’s not better than an old-school direct hiring program like the WPA, as my colleague Pavlina Tcherneva points out.

All in all, the proposal is OK, but it will not have a big enough impact, either to make a large dent in unemployment (it’s just over half as large as the original stimulus package) or to influence the election in favor of the President. But it IS better than nothing. Really.

The bitter pill in this proposal is the idea that cutting Medicare is how we’re going to pay for it. Flabbergasting! On the one hand, there is a bit of clever play in the proposal, in which the President suggests that the “Super Committee” add the bill from this bill to the tally it’s going to cut by Thanksgiving. Cute, but let’s face it: that committee is doomed to failure anyway. So does that mean the across the board cuts will have to be even deeper? Back to Medicare, the problem with Medicare is health care in this country. The program itself is just fine and would be just fine (Americans are even willing to pay higher taxes to keep it, according to polls, but don’t tell the Tea Party), if costs were not growing out of control. There are lots of good proposals to control costs, but I think looking at the fee-for-service model that we have right now is the prime candidate for reducing costs. Reductions in coverage are an unnecessary evil.

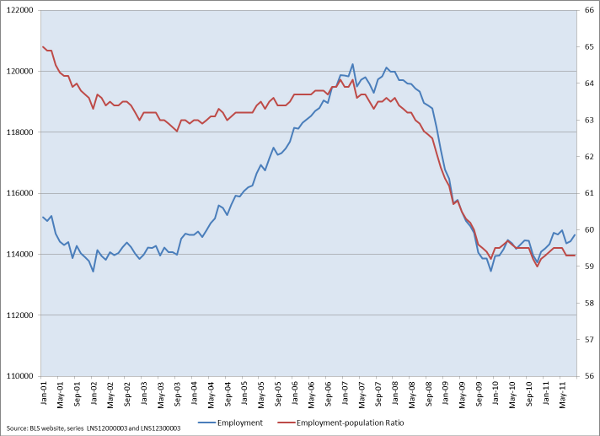

I want to take a moment to address some reactions to this plan from both the left and the right. I haven’t actually bothered to check the latter. Were the words “failed policies” used? I knew it! I heard some from the former right after the speech, when my old professor Rick Wolff gave some commentary on Pacifica. Most of what he said I agreed with, and he ended with a similar wish for a more FDR-like plan. But, he said that the ARRA hadn’t worked, and this stuck in my craw a bit. We did some estimates of its employment impact at the Levy Economics Institute, and came up with about 6 million jobs created or saved. Of course, by the time ARRA was enacted, the economy had already lost 8 million jobs, so it alone couldn’t have brought us back to pre-recession levels of employment. And of course, the rest of the economy was still in free-fall. Below, I have a chart of employment and the employment-population ratio (the percentage of the adult population employed) which I made using Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers.

You can see that the economy was losing jobs rapidly (the blue line) beginning in October 2008. The employment situation only starts to stabilize in late 2009, after the stimulus plan went into effect. There has not been significant job growth since then. Without the spending in the ARRA, the economy would eventually have bottomed out on its own, surely, but at what level of employment? Would we even be at the bottom yet? We can’t know, of course. And this is the point I want to make: the appropriate measure of the effectiveness of the ARRA in combating unemployment is a comparison that we can’t make. To say that it didn’t work because we have 9.1% unemployment (or pick any number), is an invalid argument.

We can, however, know some things about the effectiveness of the ARRA just by using a little logic. Money was spent by the Federal, State and local governments that would not have been spent, had not the ARRA passed. That spending increased incomes going into the pockets of the workers impacted, which would have been empty otherwise. Those workers spent that money, meaning the effective demand for goods and services was higher than it would otherwise have been. That increased demand meant people who would otherwise have lost their jobs kept them instead and spent their paychecks, and so on, and so on.

Now you can argue, as many economists on the right do, that the government spending just meant less private spending by businesses, etc. That the economy is essentially a zero-sum game: if the government borrows to engage in stimulus, then there are less funds available for entrepreneurs to borrow and it all balances out; except the government is worse at knowing how to spend money wisely than are entrepreneurs (like Donald Trump, the king of bankruptcies). But riddle me this: what were all those entrepreneurs doing in late 2008 and early 2009? Were they on vacation off-planet? Snarkiness aside, I don’t think much of that line of argument. I’d like it if my colleagues on the left didn’t give those people who make it more fuel for their fire by saying “the ARRA didn’t work.”

Finally, I wonder about how this proposal is ever going to get through Congress. The President is promising to go around, campaigning for it (and simultaneously, I assume, for re-election). If he does manage to convince people to get excited about this proposal, will people be able to move Congress? Congress seems quite impervious to public opinion, when it is not in tune with corporate interests, so I don’t think polling data will be sufficient. More will be required: active organizing to put pressure on congresspeople in both parties to vote for the bill. To engage that kind of mobilization, however, the President needs to be selling a bigger, better deal than this American Jobs Act.

ShareThis

ShareThis

[…] For Thomas Masterson’s extensive treatment of the proposed American Jobs Act (“equal parts weak tea and bitter pill”), see here. […]