Greece, Rock Bottom, and Co-operative Banking

In a recent interview, C. J. Polychroniou asked Dimitri Papadimitriou about the idea that Greece is on the verge of economic recovery:

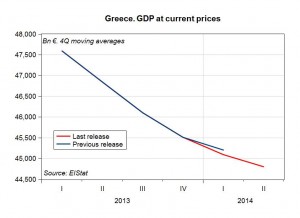

Both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Commission (EC), in their assessments of the performance of the Greek economy, appear more optimistic on the future of Greece because of the deceleration of the negative growth and a very slight decline of the unemployment rate, even though this was due to using statistics based on the new census that has resulted in demographic adjustments, and not due to growth in employment.

An artificial positive sign on Greece that indicates nothing about Greece’s economic condition, yet it was celebrated as a sign of recovery, was the primary budget surplus and “going back to the financial markets” for a new issue of bonds. The budget surplus was achieved at the cost of creating many damaged lives. On the other hand, going back to the markets was purely a public relations exercise, since the interest cost of almost 5 percent of the new bonds was much higher than that paid on the bailout funds. Moreover, the bonds were implicitly guaranteed by the ECB because they could be used as collateral to the ECB for lower-cost bank borrowing. Finally, the demand for these bonds reflected the current state of excess global liquidity available and not because investors considered Greek bonds as a good risk. The latter is in concert with the well-known adage in Wall Street that at times of “excess liquidity, even turkeys can fly.” All in all, even if the economy were to have hit bottom, this does not necessarily mean it is out of the woods and to a better outlook for its future.

In another segment, Polychroniou and Papadimitriou discussed a recent Levy Institute report that features a proposal to reform and expand co-operative banking in Greece:

Greek banks remain fragile and undercapitalized, thus unable to help the economy recover. A recent Levy Economics Institute publication strongly endorses co-operative banking for Greece as a much-needed alternative financing model for start‐up and existing small enterprises and as an all-important poverty policy alternative. Does the American experience with co-operative banking support this recommendation for Greece?

In the United States, there are no co-operative banks per se. There are what we call Credit Unions and Community Development Banks. Credit Unions have been established throughout the United States and are very successful and mostly unaffected by the subprime financial crisis of 2007-09. They were originally established to serve customers who possessed some common characteristic, i.e. employees of a large organization such as the UN, or big business – IBM – or a locality, Hudson Valley in upstate New York and so on. By now depositors do not need to share a common characteristic. The present credit unions are not very big and serve their local customers since they are geographically focused. Community development banks are very similar and provide banking services to individuals and businesses with limited credit history, such as start-up businesses, firms in agricultural and remote regions, or to inner cities that big banks do not find it profitable to extend their services to. They are doing quite well serving the interests of the unbanked.

Co-operative banks are mostly a European phenomenon and some have become very important in their respective countries and quite large. Others continue their mission of providing services, especially depository and lending functions, to people and areas that large banks shy away from. The most successful are in Germany. There is serious interest from these German co-operative banks to establish their model and operation in Greece. We don’t really need them. We can establish the Greek co-operative bank system very much different than the one we now have, which did not perform well all the time. Our proposal for cooperative banking in Greece incorporates a strong regulatory and supervisory structure, fully transparent, guided by a strong and professional board that will serve the liquidity needs not in the form of “red loans” (κόκκιναδάνεια), but to promote regional entrepreneurship. These banks would contribute to restarting the engine of economic growth, especially within the European framework of the social economy. It has been shown that the large systemic banks in Greece are still in the process of strengthening their balance sheets and have created the credit crunch I mentioned earlier.

Read the rest of the interview here.

Related: “Co-operative Banking in Greece: A Proposal for Rural Reinvestment and Urban Entrepreneurship” (pdf)

See also this policy brief from 1993, co-authored by Hyman Minsky, Dimitri Papadimitriou, Ronnie Phillips, and L. Randall Wray: “Community Development Banking: A Proposal to Establish a Nationwide System of Community Development Banks” (pdf)

ShareThis

ShareThis