Michael Stephens | November 30, 2011

Speaking of balances, late last week Martin Wolf delivered a helpful column (“Why cutting fiscal deficits is an assault on profits,” FT Nov. 24). Wolf writes that if households are cutting back, a government that attempts to reduce deficits while anticipating no substantial changes in net exports must expect corporate surpluses to shrink. But increased investment is unlikely, so: “If the government wishes to cut its deficits, other sectors must save less. … What the government has not admitted is that the only actors able to save less now are corporations. The government’s – not surprisingly, unstated – policy is to demolish corporate profits.”

Wolf is consistently worth the read.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

At Citizen Vox Micah Hauptman uses the recent Bloomberg revelations (regarding the details of the Federal Reserve’s extraordinary efforts to stabilize the financial system) to frame a discussion of Fed transparency and accountability:

The Fed has vigorously defended its secrecy, claiming that working behind closed doors is necessary to prevent panic in financial markets. According to the central bank, disclosing information about the Fed’s actions would create a stigma for the banks that took advantage of the measures, and cause investors and counterparties to shy away from doing business with them.

But these excuses just don’t hold water. When the Fed spends money, it creates a government liability, for which the public is ultimately on the hook. And when the public is on the hook, it must be done in the light of day.

Hauptman notes the recent formation by Senator Bernie Sanders of a panel of experts, featuring a number of Levy Institute scholars (including James Galbraith, Randall Wray, and Stephanie Kelton), that will make reform recommendations regarding these very issues.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 29, 2011

In a new one-pager C. J. Polychroniou illustrates how dire the situation in Euroland is becoming, running briefly through the outlooks for Greece, Portugal and Ireland, Italy and Spain, Belgium, France, and Germany. From his entry on Italy and Spain (emphasis mine):

Both nations are currently engulfed in debt flames (in spite of the fact that Spain does not have a public-finance crisis, as its debt-to GDP ratio is just slightly over 60 percent and lower than that of Germany and France, while Italy, at only 4.6 percent of GDP, runs one of the lowest budget deficits in the EU) and being administered the usual neoliberal medication (a sure way to worsen their condition!).

Read the rest here.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

In a recent interview Dimitri Papadimitriou talked about the EU leadership’s failure to prevent the euro crisis from entering its terminal phase and ran through the likely repercussions for the US financial system. Papadimitriou cites $3 trillion in exposure for US finance, half of which is mutual fund investments in European banks and sovereign debt—and he notes that this doesn’t even include the fallout from any unraveling of credit default swaps.

Unless the European Central Bank steps up as lender of last resort (an announcement that it is willing to engage in unlimited purchases of sovereign debt should be sufficient), we will see the end of the euro project, says Papadimitriou. He contrasts the Federal Reserve’s $29 trillion worth of pledges to save the banking system with the anemic actions of the ECB (less than half a trillion euros so far). This is, says Papadimitriou, a truly historic moment we are witnessing, as the European project falls apart before our eyes.

Listen to the interview with Ian Masters here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 28, 2011

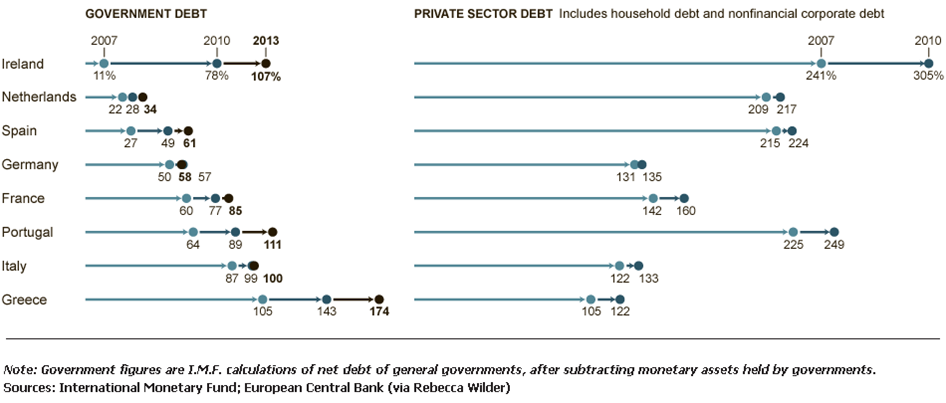

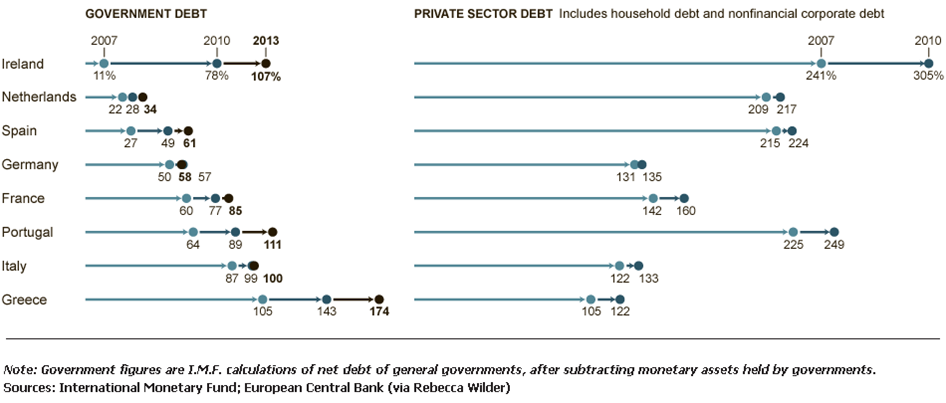

In a new one-pager, Dimitri Papadimitriou and Randall Wray team up to offer their take on the confusion that seems to afflict many approaches to the eurozone crisis. Government spending did not cause this crisis, they argue, and austerity will not solve it. Wray and Papadimitriou include this chart showing both government and private debt ratios for key EMU nations. They note that prior to the crisis only Italy and Greece were substantially beyond the 60 percent Maastricht limit for government debt. But if you look at private sector debt, every one of these countries had debt ratios above (well above, for most) 100 percent of GDP. (click to enlarge)

The problem, in other words, goes well beyond Mediterranean profligacy. “There was something else going on here;” they write, “something that has been in the works for the past 40 years: a general trend in the West of rising debt-to-GDP ratios. While government debt is part of this trend, it is dwarfed by the rise in private debt. Taking the West as a whole, government debt grew from 40 percent of GDP in 1980 to 90 percent today, while private debt grew from over 100 percent to roughly 230 percent of GDP.”

Moreover, tackling the crisis through austerity is bound to fail as long as policymakers continue to be oblivious to balance sheets. The only way that austerity in the periphery will not cripple economic growth (and therefore worsen the private debt problem) is if there is a substantial reduction in current account deficits in the periphery. But this is only possible if Germany reduces its current account surplus—and there is no evidence that key policymakers will make this happen. That leaves us, say Wray and Papadimitriou, with deflation as the only mechanism for restoring competitive balance. In other words, it leaves us with an approach that makes default, and the collapse of the EMU, more likely.

Read the one-pager here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 27, 2011

Randall Wray kicks off a discussion of the movement to reform or eliminate the Federal Reserve with a look at Andrew Jackson’s 1832 refusal to extend the charter of the Second Bank of the United States (effectively forestalling the creation of a central bank in the US):

The basis of his objection to the US Bank was its “exclusive privilege of banking under the authority of the General Government, a monopoly of its favor and support” which accorded to its owners some $17 million as the “present value of the monopoly”. Those owners consisted of an elite aristocracy of Americans and foreigners. Jackson argued that it would be far more just if Congress were to “create and sell twenty-eight millions of stock, incorporating the purchasers with all the powers and privileges secured in this act”—that is, sell the stock to the American people. “If our Government must sell monopolies, it would seem to be its duty to take nothing less than their full value”.

He also recognized that the set-up ensured a net transfer of wealth from the West to the Eastern aristocrats. Further, “Of the twenty-five directors of this bank five are chosen by the Government and twenty by the citizen stockholders” (of whom a third were foreigners). Thus, “The entire control of the institution would necessarily fall into the hands of a few citizen stockholders, and the ease with which the object would be accomplished would be a temptation to designing men to secure that control in their own hands…There is danger that a president and directors would then be able to elect themselves from year to year…It is easy to conceive that great evils to our country and its institutions might flow from such a concentration of power in the hands of a few men irresponsible to the people.” (I do love the phrase “designing men”—worthy of a Veblen or a Galbraith.)

Read the whole thing here at EconoMonitor.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 23, 2011

In a new policy note Marshall Auerback argues that discussions of how to solve the euro crisis often conflate two distinct issues: solvency and insufficient demand. “Policymakers want the ECB to do both,” he writes, “but in fact, the ECB is only required to deal with the solvency issue. When you do that in a credible way, then you get the capital markets reopened and you give countries a better chance to fund themselves again via the capital markets.”

Auerback considers a proposal that would, by addressing national solvency, give member-states the space necessary address the growth problem. The proposal (developed also by Warren Mosler) calls for the ECB to make annual distributions of euros to national governments on a per capita basis. By contrast with targeted bailouts, these per capita distributions would avoid problems of moral hazard, says Auerback. They would also provide the ECB with a more effective policy lever (withholding of payments) to ensure compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact. Concerns about inflation with respect to this plan are misplaced, he argues:

To anticipate the screams of the hyperinflation hyperventillistas, the revenue sharing proposal would be noninflationary. What is inflationary with regard to monetary and fiscal policy is actual spending. These distributions would not alter the actual annual government spending and taxation levels demanded by the austerity measures and SGP constraints. They would simply address the solvency issue, which has effectively cut the PIIGS off from market funding (because the markets believe they are insolvent).

Read the whole thing here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 22, 2011

[The following is from Joel Perlmann, Senior Scholar and Director of the Immigration, Ethnicity, and Social Structure program at the Levy Institute]

In the summer of 1967, just after the Six-Day War brought the West Bank and Gaza Strip under Israel’s control, the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics conducted a census of the occupied territories. The resulting seven volumes of reports provide the earliest detailed description of this population, including crucial data about respondents’ 1948 refugee status.

In recent decades, these volumes of tables — over 300 tables in all — have received little or no attention from historians of the occupation, not least because it is not easy to use the reports in print form and in any case the volumes are not widely available even in good research libraries.

The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College is making the contents of these volumes available in machine-readable form for the first time, free of charge to anyone with access to the internet. The tables can be downloaded in Excel format for intensive research.

Many tables provide information cross-tabulated with several social characteristics at once (for example, education or occupation cross-tabulated with age, gender and refugee status) and presented for small geographic locales as well sub-totaled for regions.

Also, in conjunction with the Palestinian Authority’s censuses of 1997 and 2007 these tables help provide an understanding of trends over 40 years. We hope that the data can be exploited by researchers interested in a fuller understanding of the social history of the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

For an overview of our project and to access the hundreds of tables contained in the 1967 Census database, go to http://www.levyinstitute.org/palestinian-census/

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 21, 2011

In the course of an interview by Alan Minsky from a couple of weeks ago, Michael Hudson discussed a proposal for setting up a public option for banking (following the “Chicago Plan” of the 1930s and, says Hudson, Dennis Kucinich’s recent NEED Act):

Instead of relying on Bank of America or Citibank for credit cards, the government would set up a bank and offer credit cards, check clearing and bank transfers at cost. …

Providing a public option would limit the ability of banks to charge monopoly prices for credit cards and loans. It also would not engage in the kind of gambling that has made today’s financial system so unstable and put depositors’ money at risk. …

The guiding idea is to take away the banks’ privilege of creating credit electronically on their computer keyboards. You make banks do what textbooks say they are supposed to do: take deposits and lend them out in a productive way. If there are not enough deposits in the economy, the Treasury can create money on its own computer keyboards and supply it to the banks to lend out. But you would rewrite the banking laws so that normal banks are not able to gamble or play the computerized speculative games they are playing today.

Hudson also argues that distortions in our tax system that encourage debt leveraging are contributing to the fragility of the financial system and worsening inequality:

Over the past few decades the tax system has been warped more and more by bank lobbyists to promote debt financing. Debt is their “product,” after all. As matters now stand, earnings and dividends on equity financing must pay much higher tax rates than cash flow financed with debt. This distortion needs to be reversed. It not only taxes the top 1% at a much lower rate than the bottom 99%, but it also encourages them to make money by lending to the bottom 99%.

Read the whole thing. An edited transcript of the radio KPFK interview can be found here at NEP (with Hudson adding some post-interview elaboration).

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 18, 2011

The European Central Bank has finally responded to overwhelming public demand and created an online game, €conomia, in which you get to direct monetary policy for the eurozone. The game appears to reward achievement in a distressingly instructive manner. According to Matt Yglesias:

…they grade you on the basis of a pure inflation targeting regime asymmetrically centered at 2 percent. I played a round in which inflation averaged -0.25% and we had a continent-wide depression in which output fell for twelve straight quarters. They gave me 2 stars out of four. I also ran a game in which inflation average[d] 4.16% and we had zero quarters of recession. They gave me zero stars even though in the higher inflation scenario I was closer to the 2% target!

So now you can wreck the European economy over the weekend.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis