Thomas Masterson | October 21, 2011

I study the distribution of wealth and income here at the Levy Institute, so I read the first five hundred words of Robert Samuelson’s Washington Post column on inequality (“The backlash against the rich,” Oct. 9th) with interest and approval. But I knew it couldn’t last. Once Samuelson gets beyond description and attempts explanation and analysis, he is clearly out of his depth.

Samuelson turns his gaze to the proposal to raise income taxes on those with incomes above a million dollars, whom he refers to as “job creators”—a Republican Party talking point that Samuelson repeats uncritically. He makes two mistakes in citing a paper, written by my colleague Ed Wolff, in which the distribution of assets for the top 1% of households by wealth (total assets minus total debt) is compared to the distribution for the bottom 80%. First, Samuelson seems to assume that those people who own privately held businesses are small business owners. Second, not all of the people in the top 1% of household wealth are households making more than $1 million a year in income.

In Ed Wolff’s paper we see that the wealthiest 1% of U.S. households in 2007 held more than half of their net worth in “unincorporated business equity and other real estate,” and only 26% in financial assets such as stocks, mutual funds, bonds, etc. It is clear that Samuelson is translating the former category as “small and medium-sized companies.” This could be an honest mistake. But it is a mistake. There is no evidence in Ed Wolff’s paper that the top 1% contains all (or no) “small business owners.” Just that they hold twice as much wealth in privately held businesses as in publicly traded businesses. And as Kevin Drum of Mother Jones put it, “[w]e’re talking about people who earn upwards of a million dollars a year, after all. You don’t get that from taking a minority stake in your brother-in-law’s auto shop.”

If we actually look at those U.S. households receiving $1 million or more in income (using the 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances, as Ed Wolff does), we are talking about 0.37% of households. In terms of the composition of their assets, the picture is pretty much the same for them as for the wealthiest 1% of U.S. households. But only 24% of the top 1% of household wealth are in the million-dollar income club. If you look at the bottom 99.6% or the bottom 80%, the picture is very different. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 20, 2011

Are you a reclusive economist-savant who happens to know how a member state might be able to exit the European Monetary Union in an orderly fashion? Would your idea appeal to a center-right British think tank? If so, you need to shave your beard and put in for the Wolfson Prize (don’t worry, with the 250,000 pounds sterling you can buy a new beard). Via Free Exchange, the winning proposal will be chosen by a panel of economists selected by Policy Exchange, a London-based think tank. Lord Wolfson of Aspley Guise, who is putting up the cash, explains what they’re looking for: “Consideration will need to be given to what a post-euro Eurozone would look like, how transition could be achieved and how the interests of employment, savers, and debtors would be balanced. Importantly, careful consideration must also be given to managing the potential impact on the international banking system.”

Some of the Levy Institute’s work on the eurozone crisis more generally can be found here:

Comments

L. Randall Wray | October 19, 2011

(cross posted at EconoMonitor)

Government Sachs posted its second quarterly loss since it went public in 1999. No doubt that has sent Washington scrambling to try to plug the leak. (Wouldn’t it be fun to listen in on Timothy Geithner’s incoming phone calls from 200 West Street, NYC, today?)

Lloyd “doing God’s work” Blankfein blamed the “uncertain macroeconomic and market conditions”—conditions created, of course, by Wall Street. And since Wall Street refuses to let Washington do anything to improve those conditions, expect much more hemorrhaging among Wall Street’s finest.

The big banks are toast, as I’ve been saying for quite some time. There is no plausible path to real profits with the economy tanking. Only jobs—millions and millions of them, as well as comprehensive debt relief will stop that.

As I wrote a couple of weeks ago:

“US and European banks probably are already insolvent. When Greece defaults and the crisis spreads to the periphery that will become more obvious. The smaller US banks are in trouble because of the economic crisis. However, the biggest banks that caused the crisis are still reeling from their mistakes during the run-up to the crisis. They were already insolvent when the GFC hit, and are still insolvent. Policy makers have pursued an “extend and pretend” approach to hide the insolvencies, however, the sorry state of these banks will be exposed when the next crisis begins to spread. It is looking increasingly likely that the opening salvo will come from Europe, although it is certainly possible that it could come … The economy is tanking. Real estate prices are not recovering, indeed, they continue to fall on trend. Few jobs are being created. Defaults and delinquencies are not improving. GDP growth is falling. Household debt as a percent of GDP is only down from 100% to 90%. While declining debt ratios are good, it is still too much to service. Consumer debt fell from $12.5 trillion in 2008 to $11.4 trillion now. Total US debt is about five times GDP and while household borrowing has gone negative, debt loads remain high. Financial institutions are still heavily indebted—mostly to one another. At the level of the economy as a whole, it is still a massive Ponzi scheme—that will collapse sooner or later… No real economic recovery can begin without job growth in the neighborhood of 300,000 new jobs per month and no one is predicting that for years to come.

Isn’t it strange that Wall Street has managed to remain largely unaffected? continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens |

Pavlina Tcherneva was interviewed recently on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “At Issue” with Ben Merens and took questions from listeners. She argues that while there are plenty of good job creation ideas available, it is ultimately the toxic political environment that is holding us back. Beginning at the 33:54 mark, responding to a question about payroll taxes, Tcherneva pounces on the idea that the federal deficit should be a policy priority: “in and of itself, the deficit should not be a policy objective.”

Download the interview here (begins at the 2:20 mark).

Comments

Greg Hannsgen | October 18, 2011

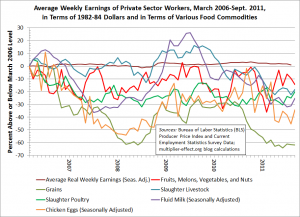

(Click to enlarge.)

(Click to enlarge.)

Signs of serious inflation in broad price indices such as the consumer price index (CPI) have been rare over the past few years, confounding many critics of the stimulus bill and the Fed’s efforts to reduce interest rates. However, as I reported in a blog entry last spring, most food-commodity prices were rising at that time and had reached levels rivaling those last seen in 2008, when unusually severe food shortages caused serious problems in many parts of the world.

The figure at the top of this post is an update of the graph in the earlier post, based on data released this morning by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The brown line shows the government’s estimate of the average real weekly wage for U.S. private sector employees. The series is of course adjusted for overall inflation, so that it represents actual purchasing power, not a number of dollars. (I have used a slightly different wage series than I used last time.)

The other lines show the same weekly earnings data series in terms of various categories of wholesale agricultural commodities, rather than a varied “shopping cart” of retail goods and services. Each line represents the value of average weekly earnings in terms of one major “food group,” to slightly misuse terminology from the federal government’s old dietary guidelines. For example, the data shown by the red line indicate that a worker measuring his or her weekly pay in an equivalent amount of fruits, melons, vegetables, and nuts would find that his or her weekly pay fell by 14.3 percent between March 2006 and last month. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens |

1. John Quiggin offers a critique of what he calls a “misreading of MMT.”

2. Bill Mitchell, interviewed by the Harvard International Review, waxes functional (emphasis added):

Particular budget outcomes should never be a policy target. What the government should be targeting is real goals, by which I mean a sustainable growth rate buoyed by full employment. Why do we want governments? We want them because they can do things that improve our welfare that we can’t do individually. In that context, it becomes clear that public policy should be devoted wholly to making sure that there are enough jobs, that poverty is eliminated, that the public health and public education systems are first class, that people who are less well off are able to become better off, etc. From a macroeconomic point of view, the spending and tax decisions of government should be such that total spending in the economy is sufficient to produce the level of real output at which firms will employ the available labor force. This is the goal, and the particular budget outcomes must serve this goal.

None of this is to say that budget deficits don’t matter at all. The fundamental point that the original developers of MMT would make—myself or Randall Wray or Warren Mosler— is that the risk of budget deficits is not insolvency but inflation…. Deficits can be too large, just as they can be too small, and the aim of government is to make sure that they’re just right to employ all available productive capacity.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

In his latest one-pager (“Dawn of a New Day for Europe?“) C. J. Polychroniou anticipates the outlines of a Merkel-Sarkozy agreement on policies designed to address the eurozone debt crisis, and comes away skeptical. Polychroniou suggests that a massive infusion of emergency funding, somewhere on the order of 2 to 3 trillion euros, would be required, but that the self-imposed necessity of operating within the constraints of the ECB’s 2 percent inflation ceiling, as well as the political challenge of passing any far-reaching measures through the national parliaments, make a sufficient response unlikely. Read it here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 17, 2011

Add central banker Mark Carney (governor of the Bank of Canada—and former vampire squidite) to the list of class traitors unlikely supporters of the Occupy Wall Street movement, calling it “entirely constructive“:

In a television interview, Mr. Carney acknowledged that the movement is an understandable product of the “increase in inequality” – particularly in the United States – that started with globalization and was thrust into sharp relief by the worst downturn since the Great Depression, which hit the less well-educated and blue-collar segments of the population hardest.

Carney, whom the Harper government is pushing as the next head of the Financial Stability Board, was also the proximate instigator of Jamie Dimon’s well-publicized tirade last month about “anti-American” financial regulation.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

Rob Parenteau has a post at Naked Capitalism commenting on Wolfgang Münchau’s article in the Financial Times. Münchau argues that policy makers in Europe largely ignored the spillover effects of simultaneous fiscal contraction across the entire eurozone. Parenteau insists that, at least at the level of ideas, the problem occurs at a much more basic level:

…while this pursuit of simultaneous, multi-year fiscal consolidation can only thwart itself by dragging down growth and dampening tax revenues, thereby leading perversely to still higher public debt outstanding, the problem does not lie so much in failure of policy makers to recognize and take into account the interactive effects of fiscal consolidation across countries. Rather, the truth of the matter is that most of the eurozone policy makers and their erstwhile economic advisors are practicing a faith based economics. They believe in the moral purity of balanced fiscal budgets. They also believe private sector activity will pick up to more than compensate for public sector cutbacks. That is the essence of the Ricardian Equivalence Theory, which is a central theoretical proposition that mainstream economists believe in and teach every graduate student to parrot.

Paul Krugman had a similar reaction:

That said, I think Munchau is being too kind here. European leaders and institutions by and large didn’t even get to the point of devising policies that might have worked in a small open economy. Instead, they went in for fantasy economics, believing that the confidence fairy would make fiscal contraction expansionary.

Parenteau points to presentations he delivered at the Levy Institute’s Minsky Conference in which he assailed this idea of “expansionary contraction” (the idea that deficit-cutting can boost growth) from the standpoint of the financial balances approach. In his 2010 presentation, Parenteau regrets that the sectoral balances approach, typified by the work of Wynne Godley, hasn’t caught on more in the mainstream—though in journalism he notes the occasional exception from Martin Wolf in the Financial Times (see Wolf’s latest column for just such a flirtation with the financial balance approach. The heterodox flavor of Martin Wolf’s writing is quite striking, as noted previously.)

You can hear the audio for Parentau’s 2010 presentation here (see Thursday, Session 4); the slides for the presentation are here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 14, 2011

Nouriel Roubini argues at Project Syndicate that widening inequality lends itself to both economic and political instability. In his latest policy brief, “Waiting for the Next Crash,” Randall Wray connects some of these same dots, tying the rise of “financialization” and soaring household debt levels to stagnating median incomes in the US:

…as finance metastasized, the “real” economy was withering—with the latter phenomenon feeding into the former. High inequality and stagnant wage growth tends to promote “living beyond one’s means,” as consumers try to keep up with the lifestyles of the rich and famous. Combine this with lax regulation and supervision of banking, and you have a debt-fueled consumption boom. Add a fraud-fueled real estate boom, and you have the fragile financial environment that made the [global financial crisis] possible.

Partly inspired by the work of Hyman Minsky (the Minsky Archives here at the Levy Institute, incidentally, are in the process of being digitized), Wray recommends a set of policy changes that are aimed at righting this imbalance between finance and the “real” economy. These include restructuring (shrinking) and re-regulating (with strict limits on securitization) the financial sector, and an “employer of last resort” policy that would offer a guaranteed job to everyone willing and able to work (federally funded, with decentralized administration). The ELR would not just be aimed at addressing the catastrophic unemployment problems associated with a cyclical downturn like the one we’re in now, but at creating a force pushing toward full employment at all phases of the business cycle. (You can read the brief here.)

Update: Read the IMF’s recent contribution to the inequality debate here and here.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis