Greg Hannsgen | August 19, 2011

You might wonder if this question is a misguided satire of Keynesian proposals like the ones in this Institute one-pager for boosting employment in a time of weak economic growth. The question is not meant as a satire, though. In a time of increasing recession fears, policies specifically aimed at reducing the value of the dollar have gained some supporters. Many scholars see a deliberate weakening of the U.S. dollar and/or a moderate increase in the U.S. inflation rate as something to be sought after in itself, not just as an unfortunate side effect of monetary or fiscal stimulus.

Kenneth Rogoff, for example, recently reprised the classic argument that the burden of debt falls when prices rise across all industries. (Rogoff’s Financial Times article is here. The New York Times discusses his views here.) To wit, moderately higher prices obviously allow firms that have debt in dollars to more easily meet their debt-service obligations. Furthermore, increases in prices often bring higher wages, albeit with a time lag, making it easier for consumers to pay off their debts on time. In the United States, this is a very salient point, in light of high debt levels in nonfinancial business and the household sector, which we documented in this recent post.

Meanwhile, on the other hand, John Plender skeptically reminds Financial Times readers (and perhaps proponents of modern monetary theory [MMT]) of the possible dangers associated with policies that intentionally or unintentionally invite a spurt of inflation. continue reading…

Comments

Thomas Masterson | August 18, 2011

mul·li·gan

noun /ˈməligən/

mulligans, plural

- A stew made from odds and ends of food

- (in informal golf) An extra stroke allowed after a poor shot, not counted on the scorecard

Casey Mulligan responds to a Paul Krugman post deliciously entitled “The General Theory of Anti-Mulliganism.” Never mind for the moment that Mulligan’s claim that Krugman admits to there being “exceptions to Keynesian theory” is, to put it most charitably, a self-serving reading of Krugman’s post. The use of the word “exceptions” sounds like Krugman is saying that in such-and-such a case Keynesian theory doesn’t apply. Of course, if you read Krugman’s piece, that isn’t the story he tells. This is merely intellectual dishonesty, though. More atrocious is Mulligan’s insistence that unemployment is caused by unemployment insurance. Why? It’s the incentives, stupid!

unemployment insurance reduces employment, rather than increasing it, because it penalizes beneficiaries for starting a new job.

Fascinating! No wonder those unemployed don’t go out and get new jobs. Because people love being on unemployment so much (they’re the envy of their friends), taking a job would certainly be a step down. See, they’d have to give up all that free time. For more money, maybe, sure, but so what? Of course a new job might also help to alleviate the stress on personal relationships, depression, anxiety, lack of sleep, and general ill-health associated with unemployment.

But Mulligan seems to think the only incentives that matter are the labor-leisure trade off beloved of Chicago school economists: the decision people make is whether more money or more leisure will make them personally better off. This is the type of decision that makes sense to Mulligan and other privileged, highly paid people, perhaps—but not to most people who would end up needing unemployment insurance. And it speaks volumes of the opinion that Mulligan and others who make the same case have of working people: if they’re unemployed, it’s because we’ve made unemployment too easy on them, and they are just taking advantage of our generosity. Or, they’re being too uppity: “employers found that people were more difficult to hire and retain when a generous safety net was available.” The unspoken assumption being made here is that the employers’ difficulties are paramount. Mulligan doesn’t explain how unemployment insurance, available to people who are laid off, not those who quit, makes it more difficult to retain people. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 16, 2011

Joe Nocera’s musings about Kurzarbeit aside, it is not the case that what we need right now are more and newer ideas for increasing growth and jobs. We do not have a scarcity of such policy ideas. What we are lacking are the political institutions that would allow us to carry any of them out. Our policy problem is a political problem.

It is remarkable how much of our lingering economic malaise can be attributed, not to the inherent thorniness of the problems we face, but to the misaligned incentives of our political system. As Greg Hannsgen pointed out in a recent post, there is no reason to believe that the United States government has suddenly been rendered unable to pay its debts as they come due. Rather, the danger appears to be that the political system (or at least an empowered minority of it) will simply refuse to do so.

This is a recurring pattern. Take the case of growth and employment. The real resources necessary for a higher level of economic activity and employment are there, sitting idle. Unfortunately, most of the textbook policy solutions lay equally idle; discarded and now beyond the realm of political possibility. We have the productive capacity, but through political choice or obstruction we are simply refusing to use it.

Under these circumstances, what should policy writers and economists do? continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens |

Research Associate Pavlina Tcherneva was interviewed by Ian Masters for his “Background Briefing” about S&P’s downgrade, the distressing new State of America’s Children report, and our misguided focus on debt rather than growth and jobs.

“If you take care of the economy, the debt and the deficits take care of themselves.”

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 15, 2011

L. Randall Wray has responded in the Huffington Post to Paul Krugman’s latest criticism of Modern Money Theory. In addition to taking issue with the usefulness of Krugman’s historical example (France after WWI), Wray discusses the evolution of MMT and the manner in which it has benefited from the rise of social media.

Update: Krugman’s newest post on MMT, from today.

Update II: Wray’s point by point rejoinder.

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 12, 2011

Senior Scholar James Galbraith’s recent article in The New Republic (“Stop Panicking About Our Long-Term Deficit Problem. We Don’t Have One”) has sparked some reactions from Paul Krugman and Arnold Kling (JG responds briefly to the latter in comments).

Galbraith, jumping off from his Levy Institute policy note, argues that there is a certain marked evasiveness in attempts to describe the dangers of the long-term deficit:

Exactly what that threat is remains elusive. Foggy rhetoric about “burdens” that will “fall on our children and grandchildren” sets the tone of discussion. The concept of “sustainability” is often invoked, rarely defined, never criticized; things are deemed unsustainable by political consensus, backed by a chorus of repetition from the IMF, headline-seeking academics, think-tankers, and, of course, the ratings agencies.

He takes issue in particular (in passing in TNR and in detail in the policy note) with the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates of the trajectory of long-term debt; estimates that depend upon assuming rising interest rates. Galbraith argues that this assumption is hard to square with CBO’s concurrent assumptions of moderate growth and low unemployment and inflation. At a bare minimum, his point here is: whatever story you might tell about the long-term deficit and debt, CBO’s particular version (which has inspired a great deal of the public commentary about future budget peril) appears to contain some internal tension.

At least in the case of Krugman, it should be noted that this disagreement about the long-term deficit is occurring against the background of broad agreement about the negligibility of short-term deficits—and, one might add, agreement over the immediate need to make those short-term deficits bigger.

(This continues an earlier debate between Krugman and Galbraith).

Comments

Greg Hannsgen |

It remains to be seen if the stock market collapse of the past three weeks or so will be followed by very bad GDP numbers and renewed job losses. How far did the recovery from the Great Recession get before the big relapse of stock-market volatility?

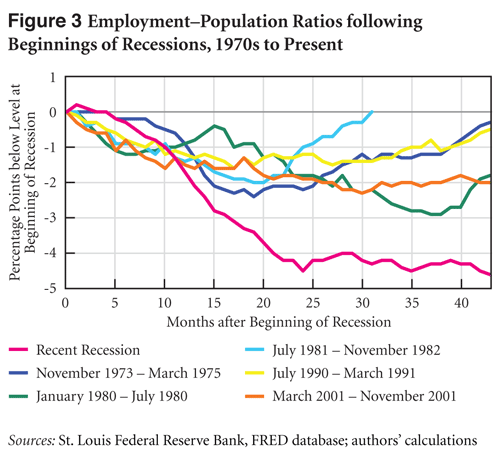

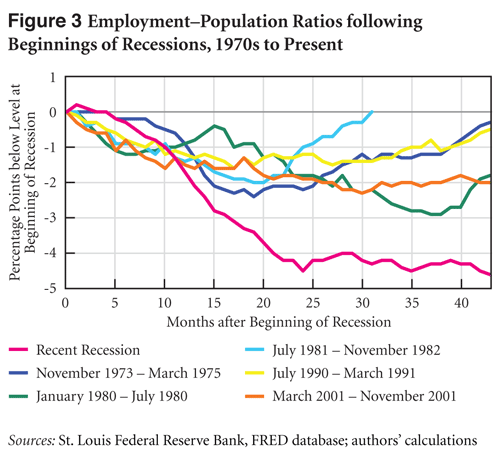

A new Levy Institute one-pager features some graphs that reveal a very weak recovery indeed, or even the start of a prolonged slump in economic growth and job creation, despite the fact that the recession ended in June 2009 by semi-official reckoning. Figure 3 in the new publication illustrates the country’s lack of progress in reversing recession-driven declines in the ratio of employment to the total civilian working-age population. Indeed, the figure shows that, according to the broadest figures available, the current employment problem is unprecedented in a period spanning back 40 years in terms of its overall size at the national level.

As the new one-pager states, Figure 3 shows

separate lines for the past six US recessions. Each line traces the path of the employment-to-population ratio relative to its level in the first month of each recession. The pink line corresponds to the most recent recession; it shows that, as of July, the ratio stood at 58.1 percent—4.6 percent less than at the recession’s start, 43 months earlier.

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 10, 2011

The topic of the moment, in the wreckage of the debt ceiling fight and the S&P downgrade, is to ask what the government can do to boost employment. The data from Gennaro Zezza’s most recent post suggest that one of the answers to this question is “stop firing so many people.”

Beyond stemming the losses in government payrolls, what else can be done to actively create jobs? (All new suggestions for boosting aggregate demand or dealing with the unemployment problem should include Peter Orszag’s just-shy-of-inspiring disclaimer from his latest Bloomberg column: “To those who will scoff that even these proposals are politically impossible, I’d note that the scope for constructive legislation has now become so narrow and the costs of doing nothing so high, we need to make ambitious proposals and hope that the legislative constraints can be adjusted.” Huzzah?)

Jared Bernstein points out that the administration’s current proposals contain two ideas that would maintain demand rather than boosting it, and one idea that would stand a chance of helping: investing in repairing roads and bridges. Due to the relative capital intensity of this last item, however, Bernstein suggests that an infrastructure program focused on repairing and retrofitting schools would have a more dramatic employment effect.

The Levy Institute’s Rania Antonopoulos, Kijong Kim, Thomas Masterson, and Ajit Zacharias have looked at another solution to this problem. Their research concludes that while the case for physical infrastructure investment is compelling, there is a public works approach that would deliver an even more impressive bang for the buck: investment in social care.

The research group proposes a direct job creation program that puts people to work addressing our deficits in early childhood care and home-based healthcare for the elderly and chronically ill. They modeled a $50 billion investment in both infrastructure and community-based social care delivery, and found that—due in large part to the higher labor intensity of care work—every dollar invested in social care would have twice the employment impact as a dollar of infrastructure investment.

Their Working Papers and Public Policy Brief can be read here, here, and here. For an abbreviated version, see the recent One-Pager. (For those of you who are (a) new to the Levy Institute website, and (b) short on time, One-Pagers are short, topical pieces that highlight policy-relevant research at the Institute—and they are indeed one page.)

Comments

Gennaro Zezza | August 9, 2011

While public discussion in the last several weeks has been absorbed by the debt ceiling saga, and in the coming weeks will probably focus on the S&P downgrade, employment (or lack thereof) is still a major problem. Our employment problem is one of the main factors contributing to a sizeable government deficit and growing public debt.

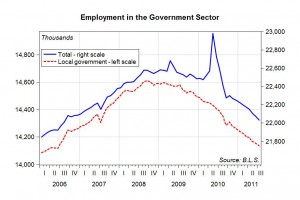

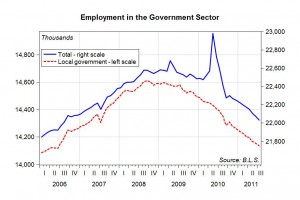

For all those who think that government has expanded wildly during the recession as a result of the fiscal stimulus, think again. The chart above shows that of the 7.3 million jobs lost since November 2007, 300,000 of those were lost in the government sector; more specifically in local government, which accounts for about 64% of the employment in the government sector. Local governments have to run a balanced budget, and when a recession hits and their tax receipts decline, they have to cut expenses—which means fewer jobs. If the federal government were to embrace similar balanced-budget policies, its ability to support a struggling economy would be severely curtailed. It would not only be unable to create jobs directly; it would struggle to even maintain its existing workforce.

The chart below shows one measure of the employment rate, computed as a percentage of the working-age population. This share rose in the post-WWII period with the increase in the female participation rate. It stabilized in the twenty years before the Great Recession at around 63%, dropped to 58% during the recession, and has remained roughly stable in the last ten months. To see what the prospects are for employment going forward, we have made some simple calculations. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | August 8, 2011

Levy Institute Senior Scholar L. Randall Wray was interviewed last week by Radio KPFK for their “Background Briefing.” Listen here to the wide-ranging discussion (beginning roughly a third of the way through the broadcast). Wray also has a piece in The Hill, expanding on his arguments about what lurks behind the hysterical focus on debt and deficit cutting.

Several of Wray’s recent publications can be viewed here.

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis