Is Stockman right about deficits, after all?

Many Americans interested in economics will recall David Stockman as the controversial White House budget director who swam against a tide of increasing deficits during Ronald Reagan’s administration in the first half of the 1980s. Ultimately, while Reagan supported many high-profile cuts to social benefits and regulatory budgets, he vastly increased military spending and cut taxes drastically, leading to deficits that disappointed fiscal conservatives. Stockman has an op-ed article in yesterday’s New York Times blasting what he sees as weak efforts by the president and congressional Republicans to come up with long-term plans to cut deficits. He disagrees with the Ryan plan’s focus on cuts to programs that help the poor and Obama’s emphasis on ensuring that the rich pay their fair share. In Stockman’s mind, these approaches to budget cuts leave the federal government’s main fiscal problems unaddressed but go down well politically.

One should take note that while Stockman’s alarms of more than 25 years ago went largely unheeded, no serious U.S. fiscal crisis materialized, though deficits reached nearly 6 percent of GDP in 1983. On the other hand, unemployment touched double-digit levels early in Reagan’s tenure, making high deficits nearly inevitable and certainly justifiable from a policy perspective. Moreover, numerous other serious problems arose largely as a result of Reagan’s economic policies, including his attack on the “safety net” of social programs for the poor.

Finally, we wish to respond to the fiscal disaster scenario that Stockman presents in today’s article. Levy Institute macroeconomists and other strong proponents of Keynes’s theories have argued in recent years that the United States should run deficits in the amounts necessary to ensure full or nearly-full employment, without fear of bankruptcy or other affordability issues connected with high deficits. We argue that unlike individual U.S. states and members of currency unions, the U.S. federal government can run deficits indefinitely without becoming “insolvent” in any sense or being forced to default. The government has this ability because the United States uses paper money that is not convertible to a fixed amount of gold or foreign currency.

Reading Stockman’s article, it appears that he might not completely disagree with these views. He observes that the Fed and other central banks have been buying huge amounts of dollars, in essence using their printing presses to provide the real “financing” for large portions of the U.S. deficits. We have noted the success of these routine operations in recent years, observing that interest rates paid by the U.S. government remain extremely low, even as it has borrowed amounts equivalent to approximately 10 percent of yearly national output. Stockman does not miss this fact, but argues that the Chinese central bank will soon reduce its purchases of Treasury securities in order to control domestic inflation, and that the Fed will also be forced to reduce its open market purchases in order to avoid destroying the value of the dollar. Then, in Stockman’s view, the game that he called into question decades ago will be over.

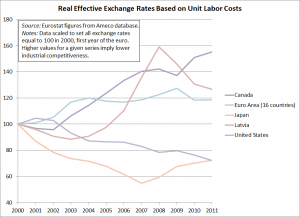

We certainly concede that the use of a sovereign currency cannot be counted on to overcome fiscal problems unless the issuer of the currency is willing to allow its value to change vis-à-vis other currencies. In the case of the United States at the current juncture, this would hopefully involve substantial real depreciation of the dollar against the Chinese currency, known as the renminbi or yuan. We have advocated such a currency depreciation for some time, though Saturday’s blog entry showed that the U.S. dollar may in fact be undervalued relative to some other important currencies. So we do not imagine that the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury possess any magic powers to defy the laws of budgeting that Stockman himself does not acknowledge in his article. The main difference between Stockman’s views on this issue and ours appears to be that Stockman opposes further declines in the U.S. exchange rate or believes that current budget plans would result in far more depreciation of the dollar than we anticipate. From a political standpoint, he believes that the Fed will agree with him on the need to support the value of the dollar, even if such a defense results in greatly increased interest rates. Hence, in Stockman’s view, the Fed will ultimately be forced to accept extremely high interest rates as a result of the high deficits of recent years, making mortgages, business loans, and so on unacceptably expensive to U.S. borrowers. In this sense, as Stockman sees it, the Keynesians will finally be proven wrong.

As of now, we feel that the overall value of the dollar may need to fall further and that while rock-bottom interest rates cannot cure the economy’s main problems, they remain desirable for many reasons. A dollar crisis could conceivably unfold, but such an event would not occur without a confluence of multiple adverse events, with the federal debt constituting only a minor factor. (Some examples of the kinds of events that could somehow precipitate a currency crisis would be a big natural disaster, a crash in another key financial market, or an economic depression.) Hence, the fiscal issues that Stockman sees as crucial should not necessitate cuts to programs like Social Security, Medicaid, or Medicare that otherwise contribute to the nation’s well-being or tax increases on families and others with modest incomes. In holding these views, we disagree with most U.S. “fiscal moderates.” Nonetheless, Stockman’s op-ed piece does a good job of establishing some key points, especially the unfairness of the Ryan plan’s attacks on domestic, discretionary, nondefense spending.

Update, April 29: Click “more” link below to see comments on this post:

ShareThis

ShareThis