Germany May Be the Biggest Loser If It Doesn’t Start Spending

There’s growing pressure on Germany to spend more to support Europe – and for good reason. But it’s proving to be a hard sell to the country’s leaders.

Germany’s budget is balanced and the government insists that its current policy stance is the best it can do – for itself, the eurozone and the world at large. The government’s mantra is that a balanced budget inspires confidence, which in turn propels growth. That’s not actually happening of course, as is plainly visible for anyone to see, yet the ongoing stagnation and sense of crisis felt across the eurozone have only encouraged the German government to repeat its flawed logic.

The rest of the world is not amused, especially eurozone members that have been at the receiving end of Germany’s economic policy wisdom and have been more actively pushing against its gospel of austerity of late.

For much of the time since the euro was launched in 1999, Germany has depended on foreign purchases of its exports for its own meager growth, particularly when domestic demand stagnated for much of the 2000s, just as it does today. But Europe’s biggest country has not been willing to return the favor, as public and private investment remain severely depressed. Even as the government has just cut its own growth forecast for this year and next, it also signaled its continued stubborn refusal to change course.

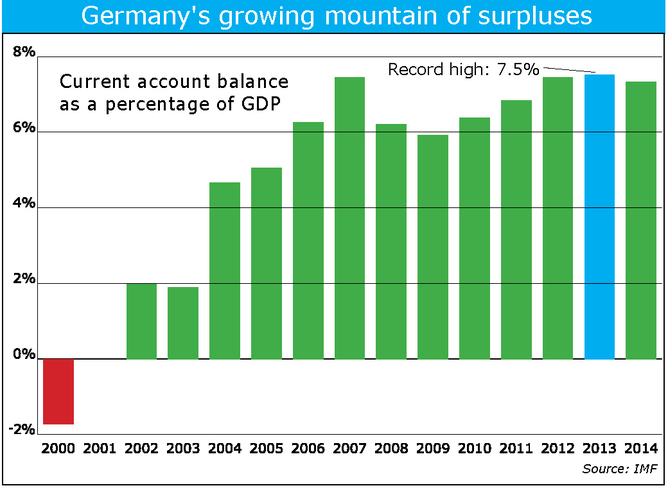

A nation of surpluses

That protracted stagnation in domestic demand helped cause Germany to run up huge and persistent current account surpluses, averaging about 7% of GDP since 2006. Germany’s current account surplus, on pace to be the world’s largest for a second year in a row, is significantly bigger than China’s, which has declined sharply as a share of GDP from 10% to 2% since the financial crisis.

Meanwhile Germany’s has gone the other way, and its leaders do not see anything wrong with that. Rather, the government views it as evidence of the country’s sound policies and restored competitiveness. Eurozone partners are invited to follow the German lead. They are told to balance their budget, liberalize their labor markets and improve their own competitiveness.

There is something fundamentally wrong about this prescription. It is actually no surprise that the eurozone remains stuck in crisis today, a crisis that is in some respects worse than the experience of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Unless the rest of the world starts booming soon – and there’s no sign that it will – the situation in the eurozone is more likely to deteriorate further than improve on its own. Germany would do itself a big favor by finally acknowledging that its own model is not working for the eurozone and change track.

‘Sick man of the euro’

It may be a good starting point to highlight that Germany’s current account surplus was a key factor in bringing about the euro crisis in the first place.

Basically, a country that runs a current account surplus earns more than it spends and acquires net claims against the rest of the world. A country that runs a current account deficit spends more than it earns and accumulates net debts against the rest of the world. Prior to the crisis the eurozone as a whole had a nearly balanced external position. But internally the eurozone became severely unbalanced as more than two thirds of Germany’s external surplus was balanced by its own eurozone partners. When Germany followed the very same policies it now prescribes to its euro partners, the predictable consequences were just as those witnessed elsewhere today: at the time, Germany was known as the “sick man of the euro.”

But Germany got lucky. As interest rates fell across the eurozone, credit and spending booms were ignited in today’s crisis countries. Their spending fired the German export engine, while German banks were all too happy to refinance loans in Spain and elsewhere. So Spain and the other crisis countries ran up net external debts that reached about 100% of GDP. When crisis struck, private lending froze, leaving the currency union divided into debtors and creditors (mainly Germany), and separated by a severe competitiveness imbalance.

Germany’s painful prescription

This is where Germany’s austerity prescriptions for crisis countries come into play. These countries are lacking the external lifeline – booming exports – that rescued Germany a decade ago. Instead, they are sinking ever deeper into what is known as debt deflation, when their attempts to reduce indebtedness actually raises the real burden of the debt. To restore their competitiveness, they have to engineer a lower rate of inflation than Germany’s, so that their goods are cheaper. That’s tough given German inflation is only 0.8%.

And restoring competitiveness by deflation is especially painful. To actually reduce their indebtedness, the countries need to run current account surpluses and grow their GDP. That requires trade partners who are willing to spend – something that is hard to come by these days.

Certainly Germany is not returning the favor of increased spending that it received during the last decade. Indeed, the German government is adamant about not spending more. The euro crisis has proved too convenient for Germany, providing super-low interest rates and a euro exchange rate that has allowed the country to shift its notorious surpluses elsewhere. But Germany will be the biggest loser if the euro comes apart. Hopefully its leaders will wake up from their austerity-propels-growth dreams before it is too late.

![]()

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

ShareThis

ShareThis