Euroland Has No Plan B: It Needs an Urgent Recovery Plan

At last, the eurozone economy appears to be experiencing some kind of recovery. GDP started growing again in the spring of 2013, following seven quarters of decline, with domestic demand shrinking for even nine consecutive quarters between 2011 and 2013. Today, it is conceivable that within a year or so the eurozone might recoup its pre-crisis level of GDP, perhaps marking the end of a “lost decade.”

But it is too soon to declare victory and become complacent. The eurozone remains fragile and the recovery uneven. Having primarily relied on export demand for its meagre growth since 2010, developments in China and elsewhere in the emerging world are posing an acute threat. More recently home-grown demand benefited from peculiar tailwinds that are temporary in nature. It is unclear at this point whether these forces will merge into a stronger self-sustaining recovery, while the likelihood of renewed and spreading political instability along the way keeps rising. It seems unwise, in fact hazardous, not to have a plan B ready at hand should growth falter once again.

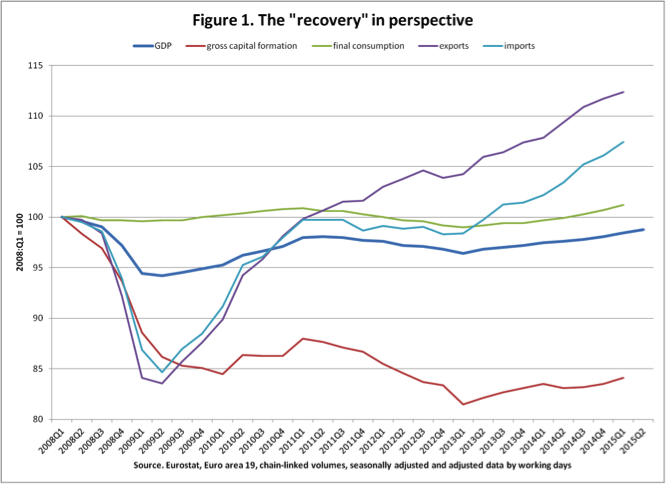

Figure 1 shows index values for GDP, gross capital formation, final consumption, exports, and imports, all relative to their respective levels in the first quarter of 2008. Remarkably, only exports have seen some real recovery. Gross capital formation, on the other hand, remains stuck at a severely depressed level to this day, while final consumption is only slightly ahead of its pre-crisis peak. Clearly, the eurozone owes it largely to the rest of the world that it has not sunk into even deeper depression.

The gaping external imbalance that has built up since the crisis quantifies the extent to which the eurozone has weakened and undermined the global recovery in recent years. Its soaring external surplus has required other countries to “over-spend” accordingly. As numerous over-spenders appear overstretched at this point, the eurozone’s external imbalance also signifies its own vulnerability to a deteriorating global environment. In a way, the ongoing deterioration in the global environment also reflects the fact that the driving forces of global growth have come full circle, and seem exhausted and spent today – unlikely to fire up again any time soon.

Before the global crisis the US traditionally played the global growth “locomotive” role. In the 2000s it became ever more daunting to generate sufficient US over-spending as more and more countries aspired to external surplus positions. So the US consumer and financial sectors got burned in the housing bubble and bust that ensued. Recovering quite briskly at first, premature austerity derailed US growth soon enough. America ceased to play its traditional role as growth engine and became a broadly neutral factor in global growth. Instead, China took over this global engine role through unprecedented policy stimulus to domestic demand. As China’s demand for commodities seemed insatiable for a prolonged period, high and rising commodity prices, both before and after the global crisis, became one transmission channel of growth stimuli to the emerging world at large. The other was gushing capital flows propelled by highly expansionary monetary policies in the US and other advanced economies. So China and the emerging world, in a fairly comfortable position at the outset, levered up fast and dirty, firing up local asset prices and spending booms.

This kept global growth alive until recently, serving as a welcome external lifeline for the eurozone in particular. But, as China sputters and commodity prices deflate, the legacies of the debt binge have come to haunt the emerging world today. International capital is taking flight, not least because of the spectre of tighter US monetary policy. The surging dollar signals that we have come full circle – only that the US seems to be in no position to pull the rest along once again.

A weaker euro was among the supposed tailwinds for eurozone recovery. Alas, with slowing global growth and currency weakening – vis-à-vis the US dollar – all round, deliberate or not, everyone’s sails keep fluttering but provide no forward pull. Improved terms of trade through lower oil and commodity prices was another supposed tailwind lifting eurozone consumer purchasing power that was otherwise starving thanks to stagnating if not declining wages. As an offset for the softer purchasing powers of commodity-exporting countries this may be fine as far as it goes, but no further. Neither currency movements nor terms of trade changes are likely to provide any net boost to global demand at this juncture.

That leaves a more neutral fiscal stance (since 2014) and easier financial conditions (since 2015) as the key domestic tailwinds behind the eurozone recovery. The ECB has belatedly started to play its part. That is highly welcome but don’t expect too much oomph from more of the same. Arguably, taking a pause from austerity has been the most important factor of all. But the breather from fiscal insanity is predicated on the assumption that the recovery will continue to broaden and strengthen.

So what if not? The risk is that the eurozone has no plan other than fresh rounds of austerity, effectively betting on global growth and even bigger trade surpluses. That would not even qualify as a sound plan B. Instead, a proper recovery plan must include a lasting return to normal fiscal policies, normal public investment spending in particular.

This is the lynchpin of the “Euro Treasury Plan” which foresees a Euro Treasury that pools future eurozone public investment spending funded by proper Euro Treasury securities. This is done in a steady fashion and both investment grants and the interest service burden on the common debt are split among members based on their GDP shares. Figure 1 shows very clearly what the problem is: to really recover the eurozone will have to invest in its own future again.

(cross-posted from Social Europe)

ShareThis

ShareThis