Are More Jobs the Answer? The “BIG” Bait and Switch

Last week Allan Sheahan published a piece arguing that “Jobs Are Not the Answer” to America’s unemployment problem. Here’s his reasoning:

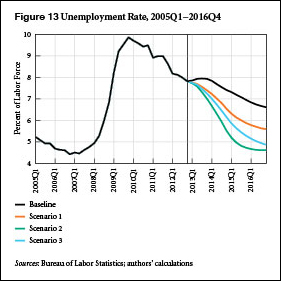

“The current unemployment rate of 7.5% percent means close to 20 million Americans remain unemployed or underemployed. Nobody states the obvious truth: that the marketplace has changed and there will never again be enough jobs for everyone who wants one — no matter who is in the White House or in Congress. Fifty years ago, economists predicted that automation and technology would displace thousands of workers a year. Now we even have robots doing human work. Job losses will only get worse as the 21st century progresses.”

In fact, economists have recognized this possibility since at least the early 19th century, when David Ricardo posed it as “the machine problem.” “Robots” have been doing “human work” since the time of Adam Smith’s pin factory. Or, indeed, since the first proto-human discovered the fulcrum and lever so that one could do the work of four.

However, “unemployment” has existed only since the development of production for market. Our tribal ancestors “worked” about a dozen hours a week to provide the food, clothing, and shelter required for the standard of life they deemed acceptable. They occupied themselves the rest of the time with all the other human activities that we regard as “culture”: dancing, singing, tattooing, shaman-ing, piercing, ritualizing sacrifices, child rearing, storytelling, marrying, fighting, debating, drawing, and thinking.

Neither were our peasant forebearers, who had access to the main means of production—agricultural land—unemployed. They might have worked much longer days, and they grudgingly turned over an ever-rising portion of their production to rapacious feudal lords, but they were not unemployed. It is only once they lost access to land through enclosures, etc, that their livelihood depended on the whims of the employing class.

Why didn’t the inexorable trend to greater use of “robots” from the time of Smith forward lead to the dis-employment of all (or most all) human labor? First we raised living standards (arguably, of course, since it is not altogether clear that we live better than our tribal cousins in all important respects), always finding other ways to employ humans to produce products that our ancient ancestors never knew they needed. Second, we reduced the workweek—adding “weekends” and “holidays,” and reducing the daily grind from 16 hours to 12, and hence to 10 and finally 8. And there it got stuck—at least in America.

Further, being a Puritanical/Calvinist sort, Americans really never embraced the idea of vacations, anyway, and so unlike every other civilized society on earth, there is no considered right to a vacation and most Americans either don’t get them or don’t want them.

In recent years, it seems that involuntary unemployment and underemployment in the US has been rising. There are a number of reasons. continue reading…

ShareThis

ShareThis