Are the Big Banks Insolvent?

Let’s look at the reasons to doubt that the big six are solvent.

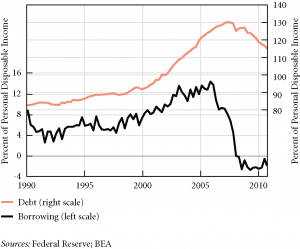

1.The economy is tanking. Real estate prices are not recovering, indeed, they continue to fall on trend. No jobs are being created. Defaults and delinquencies are not improving. GDP growth is falling. Isn’t it strange that Wall Street has managed to remain largely unaffected? Finance is an intermediate good. It is like the tire that goes on a new Ford automobile. Auto sales are collapsing but somehow tire sales to auto manufacturers are doing just fine? Does that make sense? Banks are making no loans, yet, they remain profitable?

2.Not only are the financial institutions NOT doing any of the traditional commercial banking business—lending—they aren’t doing much of the investment banking business either (remember that the last two remaining investment banks were handed bank charters so that they could scoop up insured deposits as a cheap way to finance their business). How many IPOs have been floated? Corporate debt? Trading? Well, one of the two investment banks that survived, Morgan Stanley (the sixth largest bank—barely squeaking into my “dirty half dozen” biggest banks), just released a pretty poor trading outlook—blamed on “high costs, historically low interest rates and market volatility that has pushed clients to the sidelines”. (Reuters Global Wealth Management Summit News).

3.Europe is toast. US bank exposure to Euroland is huge. But US banks are doing just fine, thank you? Hello?

4.Commodities are tanking. Equities markets are at best horizontal. Other than making profits by cooking their books, these were areas open to banks to make profits. And, yes, both commodities and equities had been doing quite well—climbing back up from the depths of the crisis. This should be put in perspective, however, because at best they only recouped losses. Still, those bubbles are now history. Losses are going to pile up. Yes, I know financial institutions hedge their long positions in commodities with some shorts—but who do you short with? Does anyone remember AIG—the insurer of first and last resort? Hedges are only as good as counter-parties, and counter-parties are no better than you are when markets collapse. In a crisis, correlations reach 100%.

5.Hedge funds have not done particularly well over the past couple of years. And yet banks have? Even though all they are doing is trading (plus cooking books and reducing loan loss reserves), the banks are far more successful than hedge fund managers at picking winners? Does that make a lot of sense?

6.And, as mentioned above, they’ve got all these lawsuits—which requires hiring lawyers, paying fees and fines, and employing Burger King kids to falsify documents. The document shredding services alone must be crimping net returns.

Ok, is there any evidence that might cause one to question bank solvency? Real hard stuff? continue reading…

ShareThis

ShareThis