Is Inequality Holding Back the Recovery?

“The biggest obstacle to a sustainable recovery,” according to the Levy Institute’s newest strategic analysis of the US economy, “is the inequality in the distribution of income.”

In their latest, Dimitri Papadimitriou, Michalis Nikiforos, Gennaro Zezza, and Greg Hannsgen begin with a familiar point: the Congressional Budget Office has been predicting fairly rosy economic growth rates for the coming years (rising to 3.4 percent in 2015 and ‘16)—rosy, that is, given the CBO’s expectation that government budgets will remain tight, and get even tighter, over this period (with the federal budget deficit shrinking to 2.6 percent of GDP by 2015).

As Papadimitriou et al. point out, the only way to make these growth and budget forecasts both come true, assuming there are no significant changes in net exports (a safe assumption), is if the private sector substantially increases its indebtedness. There really isn’t any other option. If we don’t see a return to ballooning private debt-to-income ratios, then either government budgets will have to be loosened or we won’t get the growth rates the CBO is telling us to expect.

Now, there are reasons to think that the reappearance of accelerated growth in private debt is unlikely (a theme the authors dealt with in their last US strategic analysis), but if it does happen, rising private debt ratios—which played the starring role in the financial crisis from which we’re still recovering—might destabilize the financial system. This is one sense in which maintaining tight government budgets over the next several years should not be portrayed, as it all-too-often is, as the “prudent” course of action.

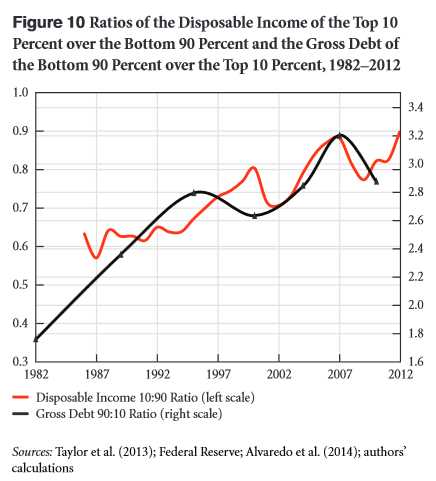

And the widening of income inequality over the last few decades makes these dynamics even more problematic. As the authors point out, the trend of rising inequality has gone hand-in-hand with mounting indebtedness among households in the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution:

[O]ver the last 30 years not only was there a sharp increase in the level of household debt but a disproportionate share of this debt was incurred by the middle class and the poorest American households. Moreover, there seems to be a strong correlation between the two variables: as the disposable income of the top 10 percent of the population increased relative to the disposable income of the bottom 90 percent, the gross debt of the latter rose relative to the debt of the former.

Going forward, the current stance of public policy (including, but not limited to, tight fiscal policy) de facto requires a rise in household debt—borne entirely by the bottom 90 percent of households—as the only path to modest economic growth rates (in the range of CBO’s 3.1–3.4 percent). If, on the other hand, the bottom 90 percent of US households continue to “deleverage,” lowering their debt loads, then the authors show that we’re more likely to see economic growth fall to a piddling 1.7 percent by 2017, with unemployment rising to 7.6 percent.

In other words, absent a change in policy aimed at loosening the government budget or increasing net exports (perhaps through targeted R&D investment), the US economy is facing one of two outcomes: “a prolonged period of low growth—secular stagnation—or a bubble-fueled expansion that will end with a serious financial and economic crisis.”

“The only way out of this dilemma,” they conclude, “is a reversal of the trend toward greater income inequality. A change in the income distribution is a necessary condition for sustainable growth in the future.”

Read the report: Is Rising Inequality a Hindrance to the US Economic Recovery?

ShareThis

ShareThis